By Frank Joyce / AlterNet

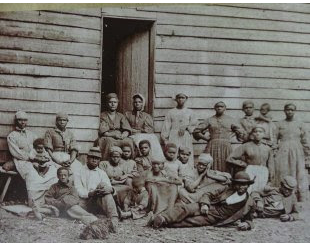

Slaves during slavery in the South. Photograph display on Gullah culture at Boone Hall Plantation.

Photo Credit: Flickr, denisbin

Slavery as practiced in what is now the United States is one of the greatest crimes and one of the greatest coverups in human history. But it is covered up no more. The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry, by Ned and Constance Sublette is a masterful forensic investigation. A profound work of scholarship and revelation, it is the story not just of chattel slavery but of the United States itself. It exposes in meticulous detail a history that has been sugarcoated, broken into pieces so tiny as to become meaningless, or often not told at all. It is a juggernaut in a new wave of books that explains our past as we have never been able to see it before.

It is one thing to understand the fabric of white supremacy and economic exploitation that is the U.S. brand of capitalism as it exists today. It’s quite another to learn how the threads were spun and woven together into what has become the biggest empire in the history of the world.

Every U.S. president until Lincoln played a role. So have many since. None however did more to set the course than Thomas Jefferson. The Sublettes unearth views of Jefferson that reveal his understanding of the economic potential of slaves, not just as chattel labor but also as a form of capital. In 1819, at age 76, Jefferson wrote in a letter:

“The loss of 5. little ones in 4 years induces me to fear that the overseers do not permit the women to devote as much time as is necessary to the care of the children: that they view their labor as the 1st object and the raising of their child as but secondary.

“I consider the labor of a breeding woman as no object, and that a child raised every 2. Years is of more profit than the crop of the best laboring man…I must pray you to inculcate upon the overseers that it is not their labor, but their increase which is first consideration with us.”

To this day, some whites commonly repeat the argument that blacks sold other blacks into slavery. This “two wrongs make a right” defense purports to offer a twisted alibi for the white slave traders who created the market for slaves, acquired them in Africa, transported them to the American continent under conditions that killed as much as 20% of the “cargo,” and then sold the survivors.

This morally bankrupt justification also conveniently ignores what whites did in creating a domestic slave business that became vastly bigger in the U.S. than the Atlantic Slave trade ever was. The American Slave Coast discloses how a sophisticated infrastructure of financiers, plantation owners, traders, haulers, marketers, lawmakers and law enforcers built an economy in which slaves became as valuable, if not more so, than the fruits of their labor. Starting in 1808, that economy severely restricted the African slave trade—not because they thought it was wrong but because they wanted to protect their domestic slave breeding and slave trading business from competition.

As with any capitalist enterprise, the domestic slave breeding and trading industry required growth to survive. Thus the powerful incentives to exterminate, forcibly relocate and control Native Americans in order to open up more territory for the growth of the plantation economy. As cotton became the number-one cash crop in the history of the world, the motivation to acquire more land for more and bigger cotton plantations exploded exponentially.

Troops led by slave-holding U.S. Army General Andrew Jackson brutally achieved this goal, thereby crafting the Indian killer reputation that got him elected to two terms as president (1829-1837) and gave him the platform from which to acquire still more territory open to slavery—a market slave breeders were happy to supply.

To comprehend the history of the domestic slave industry is to understand the formation of the institutions, the financial basis and the white supremacist attitudes of the economy that remain in place to this day. It is critical to illuminating the roots of white antagonism and cruelty toward African Americans and Native Americans that still passes from generation to generation.

Recently recognized with an American Book Award, The American Slave Coast is written with extraordinary clarity. Constance Sublette brings her skills as a novelist to the project. Ned Sublette came to this topic from a long history of writing about the convergence of slavery and music in the U.S. and the Caribbean.

Coming to terms with the truth about our past isn’t easy. Powerful forces want to tell a different story. The controversy over the Star-Spangled Banner inspired by Colin Kaepernick is a dramatic current example. The ongoing battle in Texas over history textbooks is another. So are the disputes over honoring the names of slaveowners and slavery advocates at colleges and universities.

These struggles are encouraging. Despite its nearly 400-year history, the U.S. is finally beginning to acknowledge and teach about slavery and the genocide of Native Americans as Germany acknowledges the Holocaust. Thanks to the Sublettes, Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Not Been Told, Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton: A Global History and Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz’s An Indigenous People’s History of the United States,as well as the work of activists like Brian Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative, Black Lives Matter and many others, we have more resources than ever to face the truth.

Knowing how the system was constructed is essential to working out how to take it apart and replace it with something better.

Frank Joyce is a lifelong Detroit based writer and activist. He is co-editor with Karin Aguilar-San Juan of The People Make The Peace—Lessons From The Vietnam Antiwar Movement.