By Hilary Beckles

I offer support for the objectives of Black History Month by placing on its agenda the need for an urgent Caribbean dialogue on the development challenges facing our people. Where we have reached in our historic flight to freedom as a community needs to be assessed and the depth of our dedication to promoting popular democracy should to be reviewed at this time.

We are gingerly entering the second, potentially seismic, phase of regional nation building. This in 2017 cries out for reflection. Already it presents itself as a significant marker in our regional affairs and a disruptor of global systems and sensibilities. But critically, it is the 70th anniversary of that seminal sequestering of Caribbean political and civil rights leaders at Montego Bay, Jamaica in 1947 where they outlined the road map for regional development.

The 1947 Summit, following the publication of the Moyne Report into the workers’ democracy wars of the 1930s in our Caribbean region, set the course with manifesto-style declarations that framed the first phase of the regional development agenda. Political and labor leaders were never clearer in their representation of the will of the people. They were morally courageous, fiscally sound, and financially futuristic. It was the region’s first collective rising of its political leadership.

The moment and movements were clearly defined and the political leadership was hell bent on justice, freedom, and dignified, democratic development. From Mo’bay, the Caribbean Renaissance was launched.

Today, on its 70th anniversary, there is a growing feeling of flux in Caribbean fellowship and the 1947 declarations for development seem fractured by fiscal stress. Policy priorities are less people centered and more consistent with our external financial circumstances. The top public priority is global alignment for economic growth. But economic alignment options are demonstrating that they can be socially damaging to the governance fabric of society. This is not an easy enterprise.

Communist China, our fastest emerging partner, is now the avid advocate of free trade and open borders while quintessentially capitalist America, the ancient opportunity provider, is evangelical about trade protectionism and building borders. Britain, always crisp and clear on which side its bread is buttered, has moved to abandon the European Single Market and Economy and is reckoning on returning its gaze to the recently relegated Commonwealth.

Within these global “goings on” we are seeking to determine our domestic direction and destiny. There is intense internal anxiety. At the heart of it is the growing realization that economic growth has been persistently elusive while social growth is now rejected as too expensive.

Finding balance between these equally important agendas can no longer be taken lightly. The 2016 Human Capital Report of the World Economic Forum, for example, states clearly that investing in social growth, in the human resource, goes beyond the importance of the economic growth imperatives. It states: “A nation’s human capital endowment -the knowledge and skills embodied in individuals that enable them to create economic value- can be a more important determinants of long-term success than virtually any other resource.”

The strategic reasoning that informed the Montego Bay Declarations were clear enough:

- that the imperial oppression of our people was over, dead and awaiting burial;

- that the West Indies was one social community awaiting formal political integration and economic rationalization;

- that regional institutions, like the West Indies Cricket Board which was forged exactly 20 years earlier, would be created to mobilize the best of our collective abilities for practical regional action;

- that greater social growth, in addition to economic growth, was urgently needed to end majority social exclusion, historic structural inequality, and entrenched racial and class bigotry;

- and, that our English-speaking sub-region should breach imperial barriers and reach across the blue aisle to pursue greater trade and investment with the wider Caribbean.

Where have we reached with respect to implementing the 1947 Montego Bay Manifesto? Clearly there have been many significant successes. Victories arising from the vision are everywhere discernible. Equally true is that some vanquished efforts are etched deeper in our consciousness, largely because they were bruising and bloody.

From Montego Bay we took off with dazzling speed in 1948. For four decades a transformation trail was blazed within the region. With the decade, for example, the political federation project was implemented but soon gave way to a plurality of singular nation states. The fragmented configuration has not produced a better life. The colonial carcass was only partially buried, and to boot in a shallow grave.

The social growth agenda was respected at the outset. Launched in 1948 in spectacular fashion was the University of the West Indies missile, which when nationalized in 1963, and recharged by Sir Arthur Lewis as an indigenous engine, dedicated itself to regional economic transformation, ethnic equality and social justice, and to popularizing the principle of mass political participation.

Beyond the boundary of formal politics, George Headley, born in Panama of a black Bajan father and Jamaican mother, ended six decades of leadership apartheid in the regional cricket culture in 1948 when in the Test against England at Kensington Oval he became the first player from the poor classes to captain the West Indies team. In this Test Series the 3Ws–Everton Weekes, Clyde Walcott and Frank Worrell–made their international debut. With Sonny Ramadan, our first phenomenal Indian innovator, they boldly launched in 1951 our first West Indian bid for a World title. Indeed, 1948 was the greatest of modern Caribbean years.

Today, gaining ground as a research hypothesis is that the 1947 regional development framework has been largely defeated and set aside. It is purported that a less ideologically bold and more functionalist regional leadership has revised the agenda and invested it with considerably reduced idealism, increased insularity, and greater programmatic pragmatism.

A conclusion drawn is that our region is off track in respect of sustainable development having effectively distanced itself from the 1947 beacon. Within this narrative the community is defined as manifesting many of the classic symptoms of intellectual fatigue and exhaustion. Citizens are said to be riddled with self-doubt, and primed for a race to further fragmentation.

Finally, and tragically, it is suggested that as a community we now see the primary opposition to our indigenous ideas and ideals as residing within. As a consequence, we have turned inward our vexation, violently unleashing rage upon ourselves.

The current United Nations Development Report for the region tells the bleak picture; that deep seated social inequalities and injustices reside at the core of our fractures and failures, and are the main root of shortfalls in economic growth expectations. Our region, for example, sits at the bottom of the hemispheric ladder in respect of youth (18-30 years) enrollment in higher education, professional development, and technical training. Within the wider Caribbean family context our English-speaking sub-community occupies the basement.

Equally disturbing is the inference within the Report that our social capital, that is, the cognitive and technical skills set, both in quality and quantity of our citizens, is inadequate for the attainment of the level of economic growth pursued. It has been known for decades that a shortage of critical skills, more so than capital, holds back our development. Nearly 60 percent of our citizens, for example, continue to reside in shocking shabby material and institutional environments to which we have become far too tolerant. Abject poverty is on the increase. Rising crime rates and general social insecurity in many communities seem unresponsive to the attainment of baseline economic growth.

Commitment to wealth creation, however, must be firm and unwavering. Research and innovation, and dynamic entrepreneurship, are inseparable. But economic growth must not be seen mechanically as a precondition for social growth. Low productivity is as much socially caused as it is economically impactful. It is no coincidence that our regional economy has shown the most sluggish recovery in the hemisphere from the 2008 global financial and trade recession. Inevitably linked to this chain of causality is our possession of the lowest levels of formal research, higher education enrollment and skills and professional training. It is drastically narrowing broad-based economic participation and engagement. It is impaling the people’s’ innovation impulse, endangering entrepreneurial flair and creativity, leading inexorably to diminished competitiveness and less wealth creation.

The rhetorical reference in the region to the vital role of small and medium size businesses in economic growth strategies points to the ultimate importance of the social growth agenda, and urgently awaits actualization.

The social economy, then, is equality important in viewing and measuring what we have attained and where we are today. In the Test cricket arena, for example, our fall from global awesomeness to local awfulness tells the surreal story of rising economic growth and falling social growth. We are the only competing Test nation in which senior players effectively reject national representation. By snubbing national selection in favor of personal marginal enrichment they are preventing us from deploying our best and finest in the international arena. We are crippled by our inability to be cohesive.

What is important here is that citizens are casting aside community needs and placing self above state as a post-IMF sensibility. The idea that the state has cut adrift vulnerable citizens as a conditionality of its own survival has engendered this social backlash. It has bred a political culture that will soon be entrenched with the potential to ultimately subvert the sustainability of sovereignty. This is but one example.

Our collective victories and successes since 1947 constitute the Caribbean Enlightenment and Renaissance. It is necessary to rekindle the fire of ’47. This 70th anniversary presents a lens through which we can enlarge our comprehension of the 1947 moment. The time is therefore now to review the mission and movement since Montego Bay.

A 21st century review of the Montego Bay Manifesto, therefore, is required in order to grasp the relatively greater opportunities only a regional approach can garner. The New World Group that constituted our finest intellectual and public advocacy intervention should be revisited and brought back fit and equipped for purpose. ‘New World 2’ for the 21st century is a good beginning.

Achieving greater social equality and mobility for the masses of citizens is as valuable as the fiscal empowerment of entrepreneurs for wealth creation. The legal right of indigenous, African and Asian-descendant peoples in the Caribbean to reparatory justice for crimes committed against their communities under slavery and colonialism is as important to nurturing social growth as sensible monetary measures are to encouraging investment. We in the Academy and in Industry, along with the State and Civil Society, must move swiftly towards consensus to push forward our societies and economies with innovation and technology within the context of regionalism.

The return to self-confidence to promote self-determination will not be without sacrifices. We must resolve to share this burden equitably within our regional community. This is the only way to avoid a future of further fragmentation and mutually assured deterioration. It is one way to rebuild trust in Caribbean fellowship and citizenship that is the hallmark of sustainable growth. Marcus Garvey preached this philosophy across our region before 1947 and Frank Worrell proved it thereafter.

A balanced approach to social growth and economic transformation can produce the political consciousness and corporate sensibility necessary to make many of the difficult public choices. This is the core of what we idealize as the ‘Nordic Model’. It is also the enduring feature of the Social Partners Protocol that continues after two decades to provide hope for the people of Barbados.

It is the decline in social growth in recent decades, for example, that has frustrated general support for important initiatives such as public sector reform and indeed land reform. It has also inhibited the pace of economic diversification of the traditional economic sectors.

Repurposing the passion of 1947 for regional action is entirely necessary and possible. It is a precondition for upsizing development on multiple fronts while we imagine the state of our sovereignty in 2047. Let us, then, begin a refined reflection in this year. Our precious Caribbeanness is the prime asset to be centered, cared for and celebrated as we stir our collective energy.

This is also a prime time for the academic community to move to the fore, once again, and give of its best. It must intellectually stimulate rather than frustrate the higher aspects of our collective Caribbean consciousness. Fancy fiscal footwork will not by itself generate the context for the greater growth needed.

In this regard the entire regional university sector can and must do more. It has to step up its strategies many notches and engage both the social and economic growth paradigms with greater aggression and alacrity. This Black History Month in 2017 is as good a time as ever to begin rekindling the Caribbean renaissance.

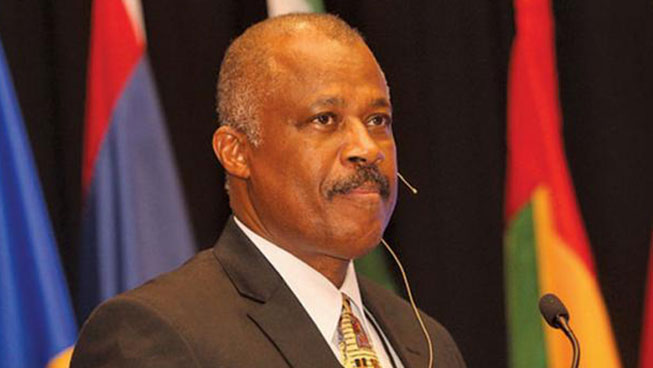

Prof. Sir Hilary Beckles is Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies and Chairman of the CARICOM Reparations Commission.