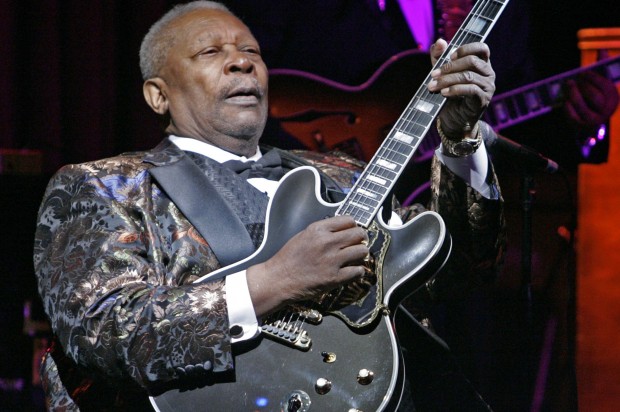

King plays during his 10,000th career performance in an appearance at his club in New York in 2006. (Credit: AP/Richard Drew)

King plays during his 10,000th career performance in an appearance at his club in New York in 2006. (Credit: AP/Richard Drew)We all have to go sometime. And hopefully, B. B. King was able to reflect in his twilight years that he had lived a longer, greater and more illustrious life than he ever might have imagined when he was born in the cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta back in 1925. He has passed away at the grand old age of 89.

I have found myself listening extensively to the blues over this past year or so. There is not a direct musical connection here to my biography of Wilson Pickett, who went straight from gospel to R&B and soul. But it has helped further inform my understanding of the culture of the deep South, the music that came out of the slavery experience, and how it then traveled, via the Great Migration, to the big cities of the industrial North. Just recently, I found myself listening to B.B. King’s classic “Why I Sing the Blues” and had to stop what I was doing to truly register the opening verse:

• • •I thought back to when I drove briefly through Mississippi this March and was taken aback by its disingenuous welcome sign, “Birthplace of America’s Music,” which offers absolutely no hint whatsoever as to how that music came about. A much more simple and accurate statement would be to call it “Birthplace of the Blues,” and leave travelers and residents alike to draw their own reference points.

Unfortunately, such revisionism is everywhere in America, and probably the world. I’m currently reading the brand new book “Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South“ by Charles L. Hughes, which takes a fresh look at the famously “integrated” studios of Memphis, Muscle Shoals and Nashville, and the mostly white musicians who played on (and produced, and owned) so much of the great soul music that came out of them. The story of how black music from the South was steadily assimilated into and by white popular culture is, thanks to the work of people like Hughes, one of ongoing debate – and “Country Soul” confirms how our own skin color, however subconsciously and perhaps even unwillingly, plays into our individual perspectives on the issue(s).

This all came together this morning, when I turned on MSNBC (a left-leaning cable station, it’s worth noting), and heard the news of B. B. King’s passing. I was staggered – though perhaps, ultimately, not surprised – when the white host noted that “among the legends B. B. King played with were Eric Clapton and U2.” You don’t have to be black, or from Mississippi, to be insulted by this statement: I would like to believe that Clapton and U2 themselves would be among the first to insist that theywere the ones who played with a legend.

This country is a better place for B. B. King. But the fact that we are still presented with such blatant racial revisionism in 2015, from the Mississippi road sign to MSNBC’s blathering, tells you a lot about Ferguson, Baltimore and more. We have a hell of a long way to go.

Tony Fletcher’s many books include “Dear Boy,” a biography of Keith Moon; “A Light That Will Never Go Out: The Enduring Saga of the Smiths” and “R.E.M.: Perfect Circle.” Visit him online at ijamming.net or on Twitter at @tonyfletcher.