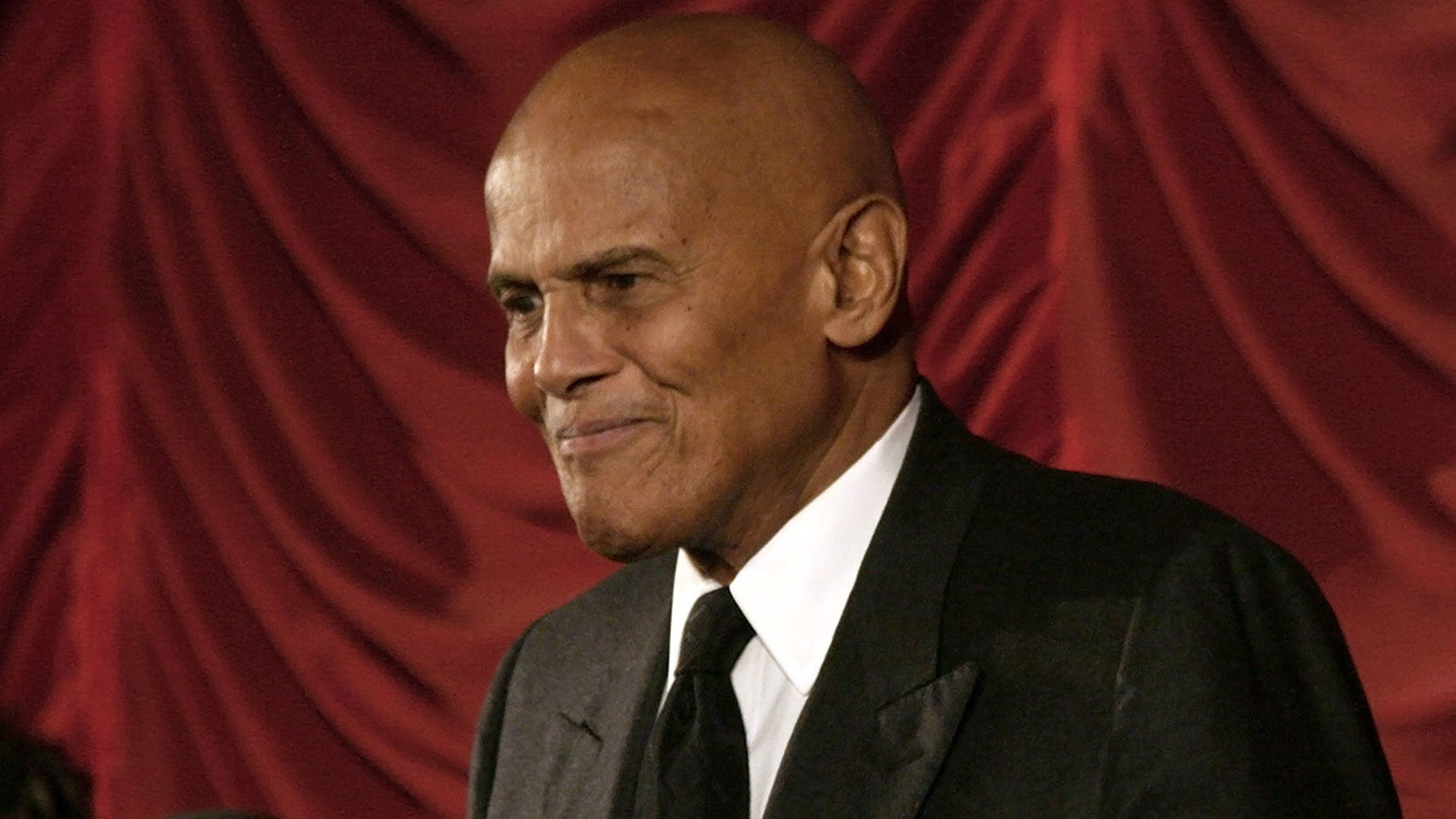

Whether on film, song, the podium or the ramparts, there was an artistic and political consistency in Harry Belafonte’s life. In the tradition of his idol Paul Robeson, Belafonte was unflinching in standing up for the downtrodden, expressing a relentless fight for civil and human rights. That principled life of conviction and speaking truth to power came to an end on Tuesday morning, according to his publicist Ken Sunshine, who said he died of congestive heart failure. He was 96.

Belafonte first attained worldwide celebrity as a calypso singer, with the millions singing along with his version of “Day-O,” a song capturing laborers in banana production, though he was born in Harlem on March 1, 1927. The popularity of that song in 1956 was just a harbinger of his phenomenal accomplishments, particularly as a singer, actor, and activist.

In 1944, after dropping out of high school, he enlisted in the US Navy. Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of his military tenure was the number of worldly-wise men he met who gave him some lessons on politics, especially the complexities of colonialism, racism, imperialism, and fascism. These encounters proved instructive and forged his contact with militant activists upon his return to civilian life.

Much of his productive life is captured in his memoir My Song with Michael Shnayerson in 2011. The hefty tome is split between Belafonte the actor and Belafonte the activist, and even some of his most ardent fans were surprised at just how much of his time, energy and resources were devoted to civil and human rights struggles.

Belafonte patterned his life and social commitments after his mentor and idol Paul Robeson, rarely ever compromising his artistic and political integrity. In fact, his art and politics were so tightly interwoven that they are as immutably consistent and unimpeachable as they are inseparably linked. One of the most memorable moments in his life was when he and his lifelong friend Sidney Poitier were couriers during the civil rights days delivering funds to the embattled Snick field workers in Mississippi. His connection to the Harlem community resonates in several significant ways perhaps most incipiently when he was a member of the American Negro Theater where he and Poitier received early tutelage in stage and screen.

A few years ago, a branch of the NYPL was named in his honor, an occasion that he shared with Cicely Tyson. Also, some of this papers and memorabilia is housed at the Schomburg Center. It isn’t easy to find one passage that summarizes his steadfast conviction and unwavering commitment to freedom, justice and equality, but this one may be serviceable: “Race was the cutting edge in everything I did,” he said about his role as a black entertainer. “To let myself be turned into an object of ridicule would undermine not just my stage persona, but my purpose as well.

And the steadfastness and outspokenness he evinced as a young man continued into the august of his years, even criticizing President Obama and calling President Bush, the “greatest terrorist in the world.” He was often unsparing in discussing the need for the younger generation to commit themselves more to voter registration and to take a stand against the rampant police abuse.

His idol Paul Robeson, in his final words as Othello, said he had done the state some service, and the same can be said and underscored in the life and legacy of Harry Belafonte.