Leading Pan-African and advocate for African unity

Malcolm X—who would be very proud of Ibrahim Traore, the Pan-African president of Burkina Faso—would have been 100 years today. Toward the end of his life, Malcolm, a great Pan-African, had also become a very passionate promoter of a United States of Africa and he’d also embraced socialism.

Most people associate Malcolm’s internationalism with his campaign to get the leaders of newly-independent African states to raise the issue of anti-Black racism in the United States before the United Nations General Assembly. It’s true that this was Malcolm’s major international initiative. After he officially left the Nation of Islam on March 8, 1964, Malcolm delivered his famous “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech in Cleveland, Ohio, on April 3, 1964. Malcolm explained that so long as the crimes carried out against Black people as a result of American racism were dealt with as a civil rights matter, it would always be within the U.S. government’s jurisdiction and nothing concrete would be done. “When you expand the civil-rights struggle to the level of human rights, you can then take the case of the Black man in this country before the nations in the UN,” Malcolm said. “Civil rights means you’re asking Uncle Sam to treat you right. Human rights are something you were born with. Human rights are your God-given rights. Human rights are the rights that are recognized by all nations of this earth. And any time any one violates your human rights, you can take them to the world court.”

However, Malcolm went beyond just trying to get the African leaders to plead the case of their African American sisters and brothers before the U.N. In the last 11 months of his life, after his departure from the Nation, Malcolm X was transformed into a global public intellectual with increasing influence and boundless potential. He also became a major critic of capitalism and imperialism.

Malcolm’s political philosophy evolved during his two trips to Africa in 1964. In March, before he traveled, he was asked by Carlos E. Russell, a member of the board of the Liberator, why he never spoke about socialism. Malcolm offered a non-committal response. “If you want someone to drink from a bottle, you never put the skull and cross-bones on the label, for they won’t drink.”

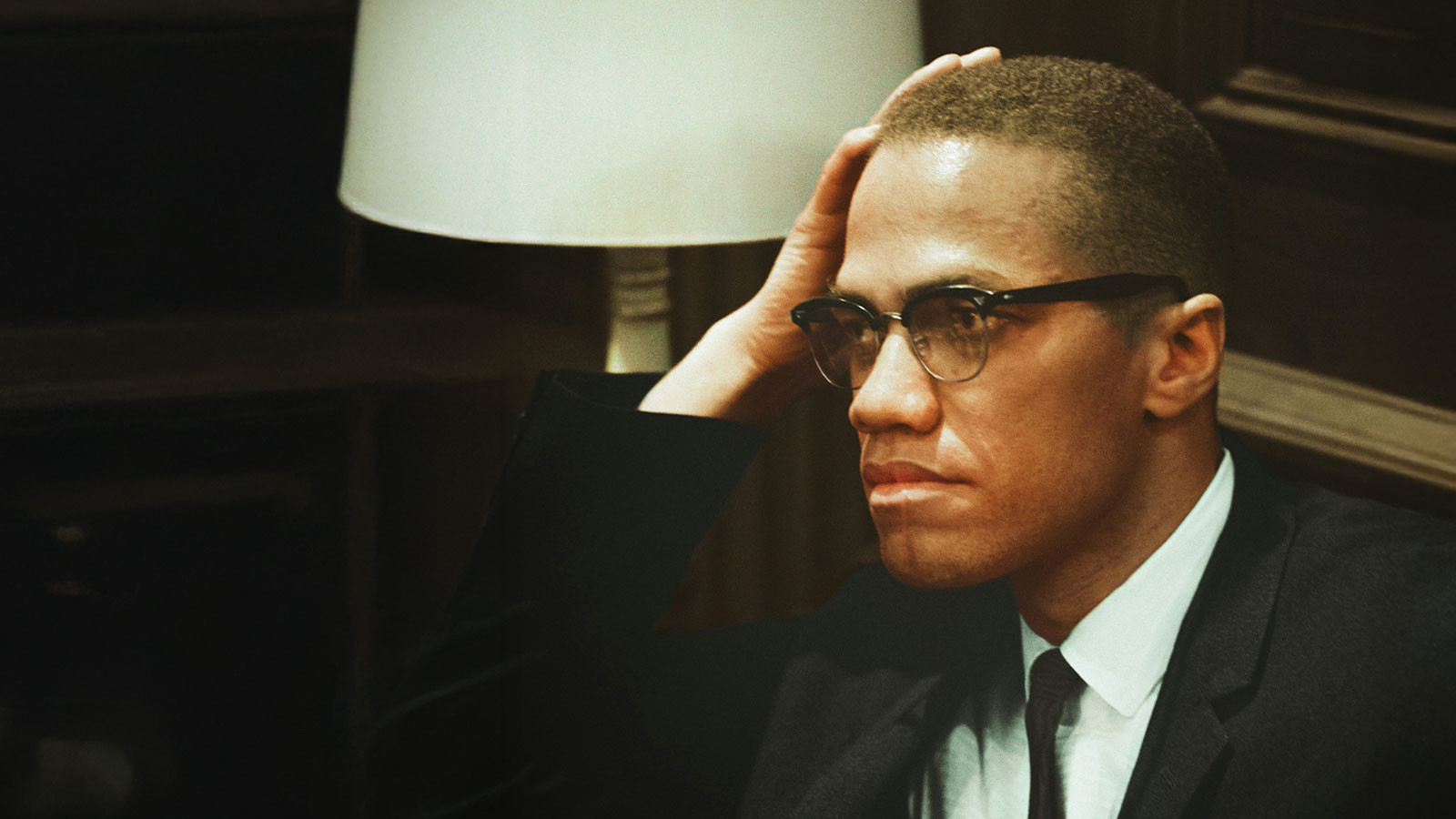

Malcolm X. Wikimedia Commons.

In April, Malcolm traveled to Mecca, where he performed the Hajj, and formally became a Sunni Muslim. He later spoke about how seeing multi-ethnic and multi-racial peoples from all over the world, worshipping together, caused him to question his analysis of African American subjugation based strictly on skin color.

Malcolm then traveled to Ghana where he met President Kwame Nkrumah, whose country had been the first British colony south of the Sahara to win its independence. There is no African who’s more identified with African unity than Nkrumah, who was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup in 1966. Malcolm was welcomed by a dynamic African American expatriate intellectual community in Accra that included Maya Angelou and Shirley Graham Du Bois, widow of W.E.B. Du Bois, who died the previous year. Malcolm engaged with Ghanaian officials, journalists, students, and diplomats accredited to Ghana, including from China, Cuba, and Algeria. These countries were led by revolutionary governments that had defeated imperialism.

Nkrumah, the leading advocate of African unity of all-time. Wikimedia commons.

Malcolm’s engagement with the Algerian ambassador, a former FNL fighter, was very impactful. The Algerian asked Malcolm where he—as an Arab—fit in Malcolm’s analysis of the liberation struggle since his skin color was white. These experiences steered Malcolm toward a class analysis approach to liberation struggle. The transformation is reflected in his speeches and interviews thereafter.

Malcolm was back in New York in May, 1964. Just two months earlier, he’d skirted a direct response to the question of socialism. Yet, when he spoke to the Militant Labor Forum on May 29, 1964, he said, “While I was traveling I noticed that most of the countries that have recently emerged into independence have turned away from the so-called capitalistic system in the direction of socialism. So out of curiosity, I can’t resist the temptation to do a little investigating wherever that particular philosophy happens to be in existence or an attempt is being made to bring it into existence.” Malcolm also said capitalism could not exist without racism.

His Pan-African activism was about to be elevated. The previous year, in 1963, the leaders of the African countries that had already won their independence met at the inaugural conference of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. Malcolm had been studying the OAU closely. On June 28, 1964, at a public meeting at the Audubon Ballroom in New York, Malcolm announced the creation of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) modeled after the OAU.

He had drafted its charter with the assistance of close associates and with the advice of scholars like the renowned Dr. John Henrik Clarke. Malcolm wanted the OAAU to be a vehicle for uniting Africans in the diaspora—African Americans, and African descendants in Europe, the Caribbean, and South America—then forming the bridge with Africans on the continent.

Later that year, Malcolm traveled to Cairo and attended the second annual conference of the OAU, in July 1964. He met Egyptian president, Pan-Arabist and Pan-African, Gamal Abdel Nasser, other African leaders, and several leaders of liberation movements fighting against White minority rule in Southern Africa. He also met Mohammed A. Babu, the revolutionary Tanzanian minister of economic planning, who became a life-long friend and political mentor, and was later hosted in Harlem by Malcolm.

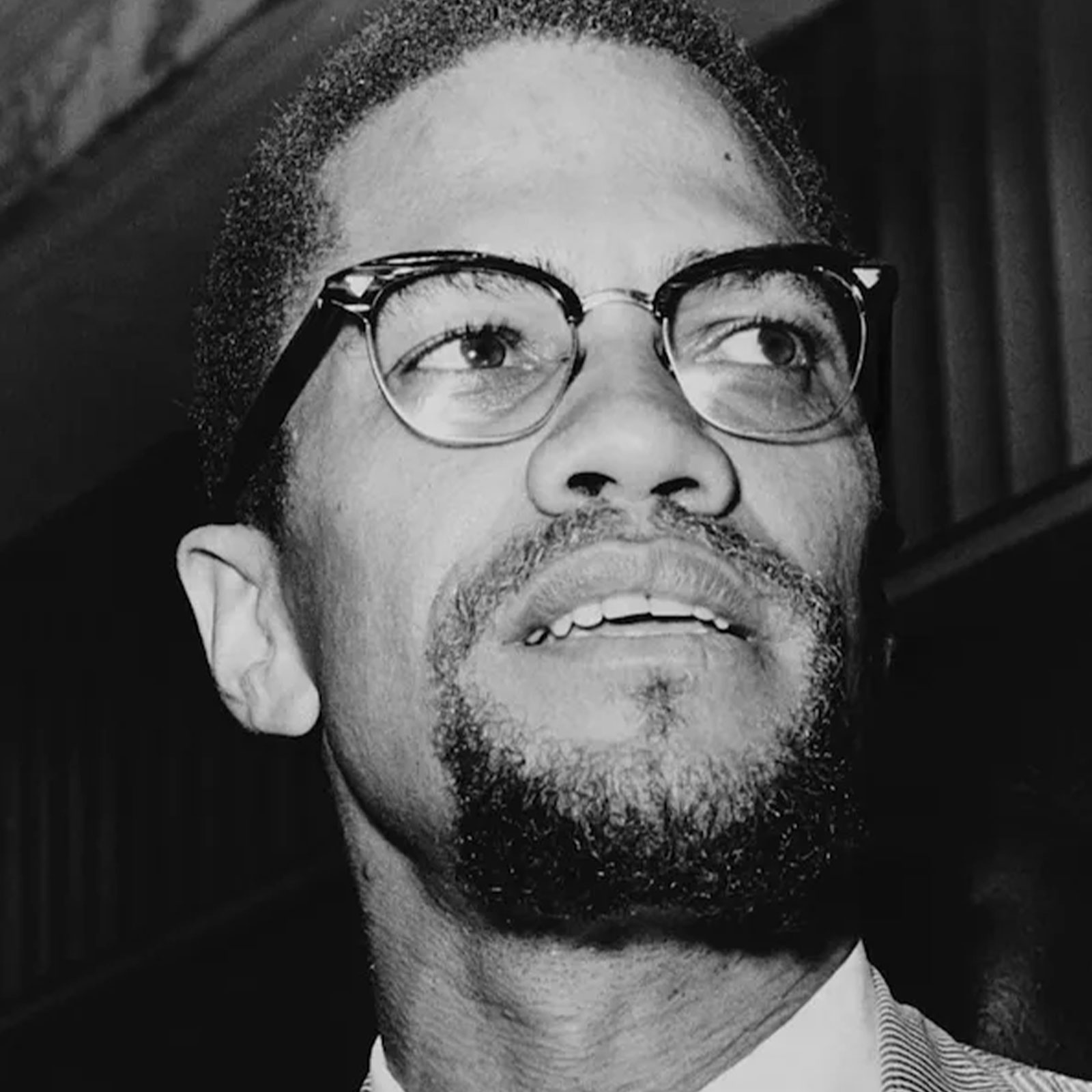

Babu, who became a life-long Malcolm friend, shown with Chinese officials.

Babu, who was a Marxist, later arranged for Malcolm to meet President Julius Nyerere in Tanzania. Publications such as The New York Times reported Malcolm’s appearance at the OAU summit as a failure because he did not get to address the heads of state from the podium. Malcolm could not have done so—even though, naturally, he would have liked to—because he was credentialed as an observer. However, he was allowed to circulate the text that he had prepared, urging African leaders to present the plight of African American victims of American racism to the UN. The summit also issued a statement condemning racism in the United States. This was a remarkable achievement and clear evidence that African leaders recognized Malcolm’s talents and tremendous potential. The Times referred to Malcolm as the “American racial extremist.” Yet even the U.S. State Department and Justice Department later acknowledged to the Times that Malcolm need only convince one African head of state.

After his visit with Nyerere in Tanzania, Malcolm traveled to Kenya, Liberia, Ethiopia, Guinea, and again to Nigeria and Ghana. He was not to return to the U.S. until November, 1964.

By the time Malcolm spoke at the Harvard Law Forum, on December 16, 1964, he was now analyzing the plight of African Americans as part of the pattern and system of global capitalist exploitation. Their conditions could be seen as a form of internal U.S. colonialism. “The African states have emerged and achieved independence. Black people in this country are crying out for their independence and show a desire to make a fighting stand for it. The attitude of the Afro-American cannot be disconnected from the attitude of the African,” Malcolm said. “The only way you can really understand the Black man in America and the changes in his heart is to fully understand the heart and mind of the black man on the African continent; because it is the same heart and same mind, although separated by four hundred years and the Atlantic Ocean. There are those who wouldn’t like us to have the same heart and the same mind for fear that the heart and mind might get together. Because when our people in this country received a new image of Africa, they automatically united through the new image of themselves. Fear left them completely.”

Malcolm denounced how Western media had played a role in driving a wedge between African descendants and Africans. The colonialists had popularized “the image of Africa as a jungle, a wild place where people were cannibals, naked and savage in a countryside overrun with dangerous animals. Such an image of the Africans was so hateful to Afro-Americans that they refuse to identify with Africa. We did not realize that in hating Africa and the Africans we were hating ourselves. You cannot hate the roots of a tree and not hate the tree itself.”

When Malcolm addressed a gathering of his OAAU at the Audubon, on December 20, 1964, he had now become an advocate for socialism. He said most of the African countries that had won their independence had devised a “socialistic system” as an alternative to capitalism. “This is another reason why I say that you and I here in America—who are looking for a job, who are looking for better housing, looking for a better education—before you start trying to be incorporated, or integrated, or disintegrated into their capitalistic system, should look over there and find out what are the people who have gotten their freedom adopting to provide themselves with better housing and better education and better food and better clothing,” Malcolm said.

Malcolm was no longer talking about skulls and cross-bones when it came to socialism. When he was interviewed for an article published in The Young Socialist, on January 18, 1965, Malcolm said: “It is impossible for capitalism to survive, primarily because the system of capitalism needs some blood to suck…As the nations of the world free themselves, then capitalism has less victims, less to suck, and it becomes weaker and weaker. It’s only a matter of time in my opinion before it will collapse completely.”

When he spoke at Barnard College, on February 18, 1965, before an audience of 1,500, Malcom said “…it is incorrect to classify the revolt of the Negro as simply a racial conflict of Black against white, or as a purely American problem.” He added: “Rather, we are today seeing a global rebellion of the oppressed against the oppressor, the exploited against the exploiter.” Western industrial nations, Malcolm said, were responsible for “deliberately subjugating the Negro for economic reasons. These international criminals raped the African continent to feed their factories, and are themselves responsible for the low living standards of living prevalent throughout Africa.”

Malcolm, who imbibed the spirit of Pan-Africanism in his childhood—his parents, Earl Little and Guyanese born Louis Langdon Little, had been Garveyites—extolled the virtues of a United States of Africa just as Nkrumah did. When he traveled to London to deliver the keynote speech at a conference of the Council of African Organizations held between February 4–8, 1965, this is what he told a reporter for the Ghanaian Times who was also at the event: “[I]f Africa failed to make efforts to establish a union government for the continent this year they would be doing harm to the cause of African peoples. History will record them as having failed both the African on the continent and the people of African descent abroad in the most crucial moment in the history of that continent,” he added.

He also said, “any African leader who fails to cooperate in the inevitable establishment of a union government will be doing a greater service to the imperialists than Moise Tshombe. Tshombe is after all retarding the progress in the Congo, but an African leader who is noncooperative in the establishment of a union government retards the progress of the entire African continent.” Tshombe was the Western puppet backed by Belgium and the United States. When Belgium financed the secession of Congo’s copper-rich Katanga region under Tshombe in 1960, the country was plunged into civil war. Lumumba was later captured by the UN with the support of Belgian and U.S. intelligence services. He was later transferred to Katanga where Tshombe and his Belgian masters brutally murdered him in 1961. The U.S. then maintained the kleptocrat and tyrant Mobutu in power for 37 years.

Malcolm had organized protests in Harlem after Lumumba’s murder, and in a speech at the Oxford Union debate on December 3, 1964 he had denounced Tshombe as the U.S.-backed murderer of the “rightful” prime minister, Patrice Lumumba.

Clearly, the U.S. had become very frightened by the impact that Malcolm was having on the international scene. After the London conference, Malcolm was supposed to address African Americans and Africans based in Paris, France, but he was detained at the airport and denied entry. Later, a spokesperson for the French ministry of the interior claimed that his speech could have provoked “demonstrations that would trouble the public order.”

Malcolm was deported back to London. The organizers of the conference that he’d been barred from attending called him and recorded a phone interview to be played for the people waiting for him to speak. Malcolm said while Black people should be willing to work with “well-meaning whites also who are interested in helping” they should be wary of liberals because “people we think are liberal are not as liberal as they profess; and the people we think are with us, when we put them to the test, they are not really with us, they are not really for the oppressed people as we think.”

Malcolm’s call for Pan-African unity was clear and resounding. “The Afro-American community in France and in other parts of Europe must unite with the African community, and this was the message that I was going to bring to Paris tonight—the necessity of the Black community in the Western Hemisphere, especially in the United States and somewhat in the Caribbean are, realizing once and for all that we must restore our cultural roots, we must establish contact with our African brothers, we must begin from this day forward to work for unity and harmony as Afro-Americans along with our African brothers.”

“Unity will give our struggle a type of strength in spirit that will enable us to make some real concrete progress whether we be in Europe, America, or on the African continent,” he added.

Later, speaking at the London School of Economics, on February 11, 1965, Malcolm debunked the media propaganda that during the crises in the Congo Western nations had intervened to rescue “White hostages,” from pro-Lumumba freedom fighters. “See, the African revolution must proceed onward, and one of the reasons that the Western powers are fighting so hard and are trying to cloud the issue in the Congo is that it’s not a humanitarian project. It’s not a feeling or sense of humanity that makes them want to go in and save some hostages, but there are bigger stakes,” Malcolm said. “They realize not only that the Congo is a source of mineral wealth, minerals that they need. But the Congo is so situated strategically, geographically, that if it falls into the hands of a genuine African government that has the hopes and aspirations of the African people at heart, then it will be possible for the Africans to put their own soldiers right on the border of Angola and wipe the Portuguese out of there overnight.”

Malcolm also said, “The Black man himself will only be respected when Africa is united, is respected, is strong. Therefore it is in the interests of us in America and the Caribbean to see that the African continent is strong and able to back us up when needed.” Clearly, judging by his global popularity by 1965, and his critique of capital and imperialism, Malcolm had emerged as a major voice against imperialism. His OAAU might have become a major force for linking African descendants in diaspora with the African continent. Malcolm might have—sooner rather than later—been able to address the heads of state at a subsequent OAU gathering. He had the talent, intelligence, and charisma to develop stronger linkage between his organization and the African continental body.

Alas, Malcolm was felled by the bullets of assassins on February 21, 1965 at the Audubon ballroom.

During a 1990 conference dedicated to Malcolm’s legacy, his Tanzanian friend, Babu, said, “As you know, Malcolm started his political struggle, at a community level. But he evolved into a national and international figure…Malcolm had the vision to see the threat that a united Third World would pose to imperialism. That threat has been expressed continuously since the end of the Second World War.”

Babu revealed that one month before his assassination, he, Malcolm, and Amiri Baraka had sat all night in his hotel room in New York discussing the relationship between race and class. “I’m telling you one thing that Malcolm had always emphasized: that if there is a class, an oppressed class who should lead the class struggle, then Black people should, will be in it. They have nothing to lose, literally, nothing to lose except but their chains.”

Today, young African leaders like Ibrahim Traore who continues the legacies of Thomas Sankara and Nkrumah, are revitalizing the Pan-African struggle that Malcolm X engaged in.

Allimadi publishes Black Star News www.blackstarnews.com He is a PhD student in the History Department at Howard University. Follow him @allimadi on X or reach him via mallimadi@gmail.com