Certainly, I’m aware that by the time this column is read, the election results will be in and we will have achieved some important electoral victories for progressive forces in the country. But from the library of lessons we constantly glean from our history and daily lives, we know that whoever wins these or any election, the struggle continues. We know too that we must celebrate and expand every victory we win, great or small, but as Nana Amilcar Cabral has taught us, “we must mask no difficulties, tell no lies and claim no easy victories”.

Still celebrating and drawing lessons from 60 years and 240 seasons of service, work, struggle and institution-building by our organization, Us, we know the value of elections, of rallies, of education, mobilization, organization and confrontation on every level for an effective and radical transformation of the established order. And we try to be present, especially where the interests of Black people are, which are national and global. Indeed, our first and continuing motto is “Anywhere we are, Us is” and we have not diverted from this sacred and self-conscious commitment since making it in the midst of the Black Freedom Movement in the 1960s.

Indeed, we are ever present in person and in heart, mind and spirit, daring to be a self-conscious part and parcel of resistance to evil, injustice and oppression anywhere and everywhere. And we stand and act in solidarity with all those who seek, demand and defend freedom, peace with justice, and justice with a shared and inclusive good for the people of the world and the world itself and all in it. And we take seriously Nana Haji Malcolm’s teaching that wherever we are is a battleline and thus our battle cry is “everywhere a battleline, every day a call to struggle”. Indeed, since the 60s, we have woke up and stood up each day declaring and demonstrating in various ways “it’s a good day to struggle”.

So, we too joined the seven million who recently united in demonstrations across the country under the theme “No Kings’. And we took and held high our signs; chanted our dissent and resistance and reaffirmed our positions on critical current and enduring issues: “No Kings, Emperors or Empires”; “Respect For All, Justice for All, Freedom For All”; “No Justice, No Peace”; “No Army In Our Streets, No War In Our World”; and “Resist, Resist, Resist”. We said not only no kings, but also no emperors and empires, for the vicious and violent politics we face is not only threats to democracy at home, but also threats to us and others around the world and to the world itself. And therefore, we insist and demand that there be no army in our streets and no war in the world, especially wars of genocide, occupation and the imperialist taking of the lands, lives and vital resources of other peoples. We seek, in the best of our struggles, then, not simply our own safety and security, our own rights and respect, but rather respect, justice, and shared good for all everywhere and all the time, as it is taught and urged in our sacred teachings.

And we raised the central and continuing battlecry of the 1960s, “No Justice No Peace” for the oppressor has no right to security with his jackboot on our necks, his drones overhead spewing death and destruction, and his bankers and billionaires building real and imaginary rivieras on the dead bodies of our martyrs. And thus we say with Nana Henry Highland Garnet, we are morally compelled to “resist, resist, resist”. We also know that as much as we might want an election or person to come and turn things around, as Nana Frantz Fanon taught, there are no miracles or magic solutions except those made by the masses in righteous and relentless struggle.

In our struggles and especially in times like these, there is always a need for moments of meditation on how we are to imagine a new society and world and move forward to achieve it. And always, we must turn to the sacred teachings of our honored ancestors for moral and spiritual insight and grounding. In the sacred teachings of our honored ancestors in the Odu Ifa, there is a moral narrative about the struggle, both with ourselves and against opposition, to bring, increase and sustain good in the world. It speaks of people who come into power and forget the lessons of the value of shared power and their responsibility to those who put them there. Even the righteous leader who intends to do good must always, as Nana Aimé Césaire taught, keep in constant revivifying contact with the masses and be always motivated by the idea of achieving an inclusive and shared good. And that means as Nana Mary McLeod Bethune taught, daring to remake the world.

Odu 9.1 is a teaching on the right use of power as a means to open the way for ourselves by opening the way for others. It begins with the assertion that a powerful person usually seeks maximum power which is symbolized here by the “craving for the crown,” i.e., the power of the royal ruler and all its benefits. This is part of the corruption and misuse of power we are witnessing in the emerging fascism and deepening authoritarianism in this country and around the world. The text says literally “the powerful person cries for the crown”. Given such a craving for maximum power, the person of power must sacrifice in order to use power rightfully and to cultivate moderation in one’s desire for increase and use of power. It suggests that we don’t have to be kings and queens to live a good life and that serving, itself, is greatly rewarding. This Odu offers three objects of sacrifice which at the same time are symbols of areas of self-sacrifice.

Here the prescribed sacrifice, i.e., the transformative giving of oneself, for the person is the sword, the rooster and the roasted yam. The sword is to be sacrificed as a weapon of war and aggression and used instead to open the way to the good life through struggle internally and externally. The rooster is symbolic of the sacrifice of giving up of the aggressive arrogance of power, in a word, the “cockiness” associated with the rooster or cock. And the roasted yam serves as a symbol of the sacrifice of unchecked satisfaction of physical needs and comfort whose pursuit with power leads to excesses against others and destructive self-indulgence.

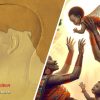

The orisha and Master Teacher, Ogun, is the perfect example and focus for this narrative on power, for he is the orisha of war, iron, technology and related areas. He is told at the outset that his sword will be the key instrument in his pursuit of prosperity or the good life. It is both the symbol and source of his power, the instrument of his work and the opener of his way to the good life. I read this sword as symbolic of struggle in its various forms for good in the world. In this sacred narrative, he sees two people fighting over a fish they both have caught, one from the East and one from the West. And he could have simply took the fish for himself through killing them, robbing them or both. Instead, he acts as a righteous judge and advises patience and the sharing of a common good. When they refuse, he uses his sword, power, to cut the fish in two.

By this act, he “opens the way” for their sharing and thus the practice of justice. Justice here is a shared good and it reminds one of the ancient African teaching in the sacred Husia of ancient Egypt in which the officials say, “I judged so that both parties were satisfied.” It is important to note also that Master Teacher Ogun, as judge, is required to listen before deciding or acting, even though he had the power to impose his wishes arbitrarily. However, this would not have been justice but rather the arrogance or “cockiness” of power. As a righteous and responsive judge, his responsibility is to “open a way” for justice to emerge, a justice of shared good, regardless of whether one comes from the East or the West. And this is what he does.

In addition to using his power to open the way for justice and sharing, the Master Teacher Ogun also uses his power to open a way for the traveler. This “way opening” is both literal and figurative, both actual and symbolic. He actually clears a road so that the two persons can use it to reach their respective cities in the East and in the West. It is here that he is promised compensation for his work which points towards his realization of prosperity in abundance through aiding others. The central lesson here is that it is by opening the way to good for others, that we open the way to good for ourselves. The journey to the city is a metaphor for our journey through life to a good end. And Master Teacher Ogun’s example of opening the way for himself, by opening the way for others is an invaluable model of how we can live full, good and meaningful lives of shared and inclusive good in the world.