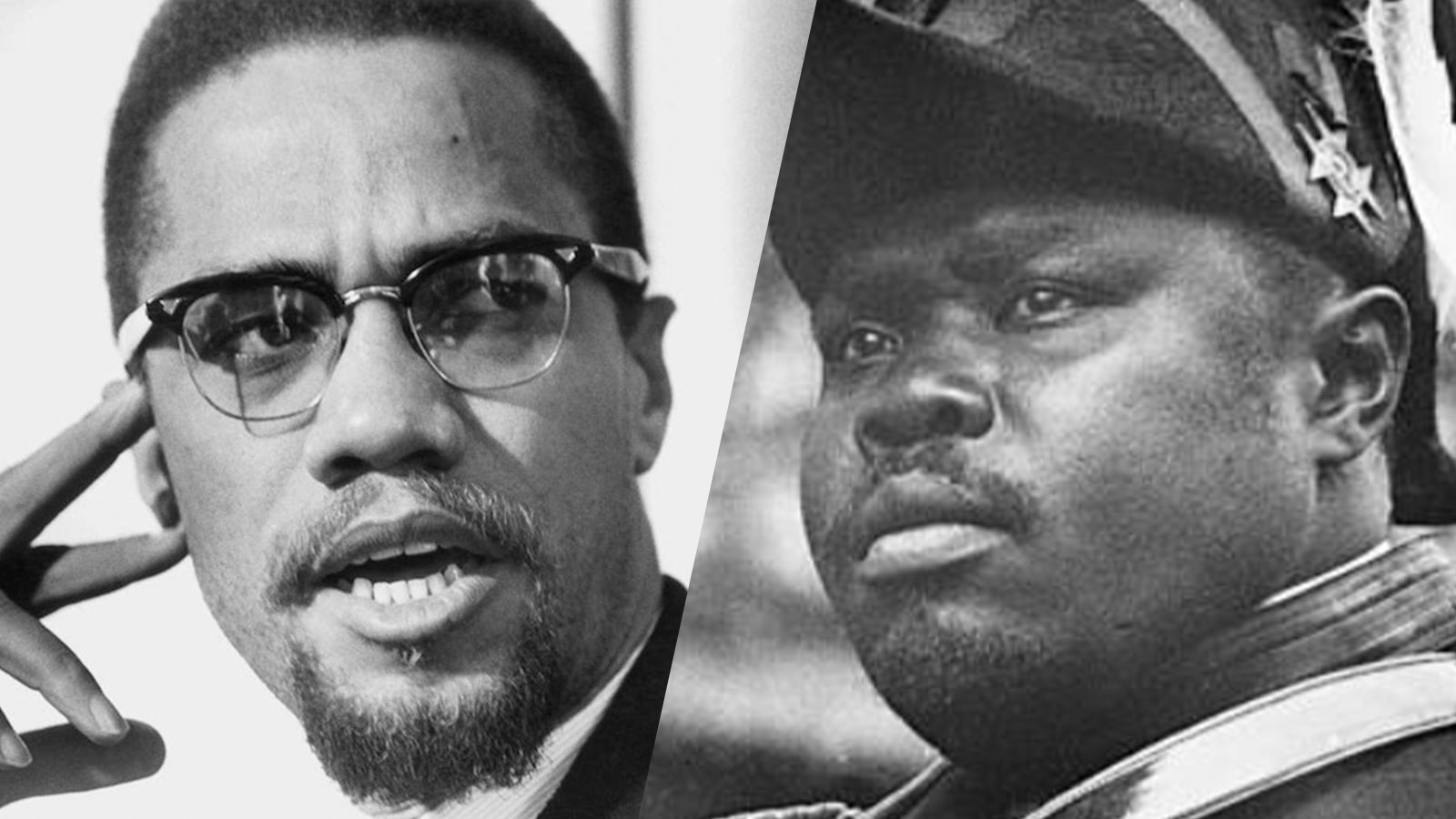

Continuing our conversation with Haji Malcolm in this his birth month of May, I want to also pay homage to a central source of his grounding and growth, the Hon. Marcus Garvey. Haji Malcolm’s introduction to nationalism and pan-Africanism began at an early age with an introduction to Garveyism, the paradigmatic and foundational urban nationalism from which all nationalists draw in various ways. In explaining his embrace of Black nationalism as a philosophy of liberation and struggle he states: “If you remember, in my childhood I had been exposed to the Black nationalist teachings of Marcus Garvey – which, in fact I had been told had led to my father’s murder. Even when I was a follower of Elijah Muhammad, I had been strongly aware of how the Black nationalist political, economic and social philosophies had the ability to instill within Black men (and women) the racial dignity, the incentive, and the confidence that the Black race needs today to get up off its knees and to get on its feet and to get rid of its scars and take a stand for itself”.

It is from his father, Nana Earl Little, who took him to U.N.I.A. meetings, he tells us that he learned of Nana Garvey. And although Nana Malcolm does not discuss it, he also learned much about Nana Garvey and Garveyism from his mother, Nana Louise Little. As Malcolm was growing up, his mother, reaffirmed these concepts, and together with his father, read to Malcolm and his siblings news and stories from the UNIA paper, taught them to sing the UNIA’s national anthem, and instilled in them a respect for their identity, history and heritage, and a pan-Africanist and global consciousness which were key to Garveyism. She also worked with her husband to organize a UNIA meeting place or Liberty Hall, as they were called by Garvey, assisted her husband with general UNIA work, served as branch reporter and “was responsible for sending news of chapter activities to Garvey’s international newspaper, the Negro World”. Malcolm would later emulate both these organizing and journalist initiatives within his work in the NOI and afterwards, as well as use Garvey’s thought and practice as models to teach and emulate.

Within the context of Haji Malcolm’s embrace of Nana Garvey and lessons learned from him about nation-building, his stress on “waking up, cleaning up and standing up” are clear and essential. Certainly, the lessons of self-determination and self-reliance stand out. Haji Malcolm praises Nana Garvey as a militant leader who was able to be militant because he didn’t seek funds and favors from the oppressor, but instead relied on the people. Indeed, Malcolm says that instead of Garvey’s seeking help elsewhere, “He asked our people for help. And this is what we’re going to do. We’re going to try and follow his books”. Moreover, he offers Garvey as an instructive model of a leader who develops deep roots among the people and was “a real leader who appealed to the masses,” who “had mass appeal . . . and frightened the government and power structure to death”, so much so they framed him, put him in captivity and deported him. The lessons here for Malcolm are courageous leadership based in the masses and by implication, a leadership that loves, lifts up, serves and struggles to liberate the masses.

Also, Malcolm saw his pan-African initiatives as a continuation of Garvey’s work for global pan-African unity and struggle. In addition, Malcolm at a forum at Harvard defends Garvey’s initiatives against contentions that he failed and poses his work as seed planting for those who came afterwards. Thus, Malcolm reinterprets Garvey’s project and achievements and honors Garvey’s stress on a people’s responsibility to write and interpret its own history in dignity-affirming, critical, correct and accurate ways, which was a continuing concern of Malcolm also. This meant to Malcolm that Black history should not be left to the oppressor or to those taught and molded by the falsification of history conducted by their oppressor. Thus, reinterpreting Garvey’s work and stressing Garvey’s agency, Malcolm asserts that “Marcus Garvey . . . gave a sense of dignity to the Black people . . . organized one of the largest mass movements that ever existed in this country”, built this movement on mass appeal and the call to return to Africa, and developed a Black nationalist philosophy that “inspired President Nkrumah of Ghana,” a philosophy “that has been spreading throughout Africa and that has brought about the emergence of the present independent African states”. Reaffirming agency rather than deficiency, Malcolm concludes saying, “Garvey planted the seed which has popped up in Africa – everywhere you look”.

From Garveyism, then, Malcolm had available an expansive corpus of teachings and concepts from which to borrow and on which to build. In addition to those noted above, these include the quest for African redemption; the indispensable need for unity and organization; the necessity of self-knowledge and self-respect; the priority of Black; the importance of a God understood and engaged from a people’s own experience; religious, political, cultural and economic nationalism; nationhood; self-reliance and self-determination, pan-Africanism; internationalism; anti-imperialism; and the value and meaning of history. It is this stress on history which forms the foundation and focus of Malcolm’s educational thrust and his ethical concerns about knowledge and respect of oneself and one’s people. Malcolm’s concept of liberation, then, is both a spiritual and political promise and practice and evolves first from the teachings of Marcus Garvey and his Garveyite parents with their stress on African redemption, a spiritual and political concept.

Here Nana Garvey posed a fundamental principle of nationalism, the liberation of the nation, the people, and its culmination in independent statehood. It is for him the essential means of defense, development and flourishing. Thus, he states, “Nationhood is the highest ideal of all peoples”. As the highest ideal, independent nationhood is also articulated as the inalienable right and responsibility of self-determination for persons and peoples. Haji Malcolm would find this central concept in various philosophical forms in the teachings of the Nation of Islam and join it with his concept of revolution as put forth in his “Message to the Grassroots” speech.

Malcolm’s conception of the redemption/liberation of Black people is also reflective of the world-encompassing reach of Garvey’s project and concerns. Indeed, Garvey had declared in affirming the world-encompassing character of his project and concerns, “I know no national boundary where the (Black people) is concerned. The whole world is my province until Africa is free”. Garvey consistently challenged Black leaders and Black people to think and act globally, not only in the interest of the liberation struggle, but also to engage in cooperative projects of progress and a just and sustainable peace with other nations and peoples of the world

It is this global conception of Black people’s presence and interests that Malcolm finds again in Messenger Muhammad’s concept of the Black man’s presence in and concern for “the whole planet”, and is also reflected in his later pan-Africanism, pan-Islamic unity, and Third World interests and engagement. This stress on the rootedness of Malcolm’s internationalist consciousness and commitment in Garvey’s and Muhammad’s teachings is important and offers a necessary and accurate corrective and alternative to assumptions and contentions that such a global and internationalist orientation is post-NOI and post-nationalism. Indeed, it is in the teachings of Nana Marcus Garvey and Messenger Elijah Muhammad, as well as other nationalist and pan-Africanist thought, that a world-encompassing conception of African interests, of African peoples’ actual and potential allies and of the nature and needs of the liberation struggle in Haji Malcolm’s liberational thought finds its first footing and foundation.