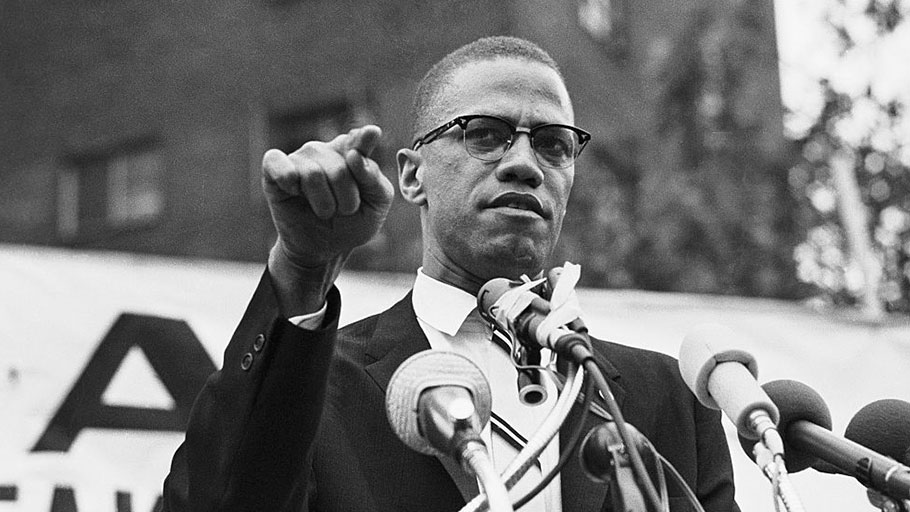

In this month and historical moment of remembering and raising up Nana Malcolm X as a mirror and model for us and the world, we must make sure it is righteous and rightful remembrance. Indeed, it must be a critical remembering that reaches back in the practice of sankofa, retrieving the best of his moral sensitivities, thought and practice and using them to ground our lives, inform our work and guide our ongoing struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves. For Haji Malcolm wanted us to become and be our beautiful Black and sacred selves through a righteous and relentless struggle to free ourselves from the various kinds of chains imposed on us by our ruthless oppressor. Indeed, he taught and Kawaida reaffirmed that our struggle at its heart is always to be ourselves and free ourselves. In a word, it is to be ourselves so we can free ourselves and to free ourselves so we can fully be ourselves.

Min. Malcolm X’s unchanging challenge to us as a people and persons to “wake up, clean up and stand up” is a constant and clarion call: to come into and cultivate an ever-expanding consciousness of ourselves and the world; to ground ourselves in the best of our ethical sensitivities, thought and practice; and to raise up and remain standing and struggling in the interest of a good world for us as Africans and for humanity as a whole. And on this another anniversary of his historic birth and coming into being, we honor him best by reexamining the instructive and enduring legacy he left and by trying to integrate it meaningfully in the forward focus and thrust of our lives.

Haji Malcolm’s message is rooted in a liberation ethics, a critical reflection and practice of ongoing personal and social transformation which forms and frees our strongest selves, and directs us toward the good and expansive lives we long for and deserve. Nana Malcolm saw in us a great and ancient people, root and reflection of “the soul of Africa” and obligated to accept the awesome role of struggle, history and heaven had assigned us. He said, “I don’t think that anything is more positive than accepting who you are.” And this means accepting our fundamental role as a moral and social vanguard in this country in a still unfinished fight to expand the realm of freedom and justice in the world and acting accordingly. Haji Malcolm continues with a call for a moral grounding that upholds, in the most empowering and expansive ways, the African ethical imperative to always act in honor of the dignity and divinity within us.

Within his third major focus, the moral challenge to stand up, Min. Malcolm stresses the transformative character and essentiality of practice, for he understands that practice proves and makes possible everything. Standing up in Nana Malcolm’s liberation ethics encompasses three basic practices: (1) bearing witness to truth; (2) living the truth of a recovered and reconstructed self, and (3) struggling to achieve a context of freedom, justice and equality indispensable to realizing the fullness of our personhood and the possibilities within us. To bear witness to truth is to teach and uphold the good and expose and condemn evil, to speak up in the midst of fear and silence, to refuse to go along and get along with oppression and oppressors and to reaffirm the right to a good life for everyone.

Haji Malcolm’s teaching on standing up, like his other teachings, is both rooted in and reflective of his own personal recovery and reconstruction. His experience teaches him that standing up is essentially offering one’s life and death as a “testimony of some social value,” in a word, being willing to live and die as a mirror and martyr for liberation and securing good in the world. This morality of self-sacrifice in the cause of liberation and a better society and world and humbleness about what one can do and has achieved are at the core of Nana Malcolm’s ethical concept of standing up.

Also, Haji Malcolm poses standing up as constantly steering and staying clear of things which would undermine our commitment to a rightful and righteously good life and our capacity to contribute to the struggle to achieve this goal. The personal battle to stay upright and committed to the struggle for the good is for Min. Malcolm a daily and ongoing challenge. But he believed that even as he had been able to stand up and sustain himself in the context of community, so can others with adequate self-assertion and support. Offering himself as an undeniable example of moral resurrection and rootedness, Min. Malcolm states that having made the commitment and passage, he can and must bear witness to its possibility and promise. For he says, “I myself, being one who was lost and dead, buried here in the rubbish of the West”, suffering from evil and ignorance, misled and manipulated was finally able “to stand upright, perpendicular. . .” and “for the first time in 400 years to see and hear.” And it is this retrieved and reconstructed capacity to hear and see from a position internal to his culture and pointing outward towards the world that gave him a solid sense of history and the promise of personal and social transformative struggle.

For Haji Malcolm, to stand upright here has three essential meanings. First, it is to stand in confidence and courage born of knowledge, knowledge of oneself in the historical and cultural sense and of the possibilities inherent in this grounding. Secondly, to stand upright is to stand in righteousness, free from vices and rooted in virtues which elevate and strengthen. And finally, it is to stand up courageously in practical struggle to transform oneself and society.

This practical struggle which one is compelled to wage is essentially for freedom, justice and human equality, a context indispensable to human life and human flourishing. As Haji Malcolm states, “freedom is essential to life itself” and “to the development of the human being.” Moreover, he continues, “If we don’t have freedom, we can never expect justice and equality.” For “only after we have freedom, does justice and equality become a reality.” It is this stress on the priority of human freedom as the grounds and context for justice, equality and human development that leads Haji Malcolm to argue the right to achieve “freedom by any means necessary.”

Min. Malcolm’s ethical vision is rooted, then, in the concept of the human person’s capacity for self-transformation exemplified in his own personal passage from lumpen life to a life of righteousness, responsibility and self-conscious struggle. Thus, his fundamental lesson is his own life, the way he turned himself around, raised up, resisted and broke the racist restraints imposed on him and became a man among men and women, a leader among the leaders of the world, and a noble witness for his people to the world. It is this also which aided in grounding his faith in the masses and in their capacity to create progress, push their lives forward and lay the basis in struggle for a new world. Like Nana Frantz Fanon’s wretched of the earth, the masses are for Haji Malcolm, capable of “the most drastic change,” are “the most fearless” and “will stand the longest” in the struggle for a new world and a new history of humankind.

Finally, Haji Malcolm reminds us, as we remember and honor him, that “a people is like a (person). Until it realizes its own talents, takes pride in its own history, expresses its own culture, affirms its own selfhood, it can never fulfill itself.” And it is only through our struggle to fully become and be ourselves and to remake society in the interest of good in the world is this fulfillment and flourishing possible.