As the country and the world experiences and resists the rise and expansion of rightist forces and their attempts to limit and deny freedom and justice, the seminal works of Nana Frantz Fanon come into sharp focus. Especially relevant here is his treatment of the psychology of liberation as both normative and necessary in the context of oppression and his insightful analysis on overcoming what he defines as “the pathology of freedom”. I read this as the pathology of unfreedom or the pathology of oppression which is a disease imposed on freedom and therefore creating a diseased and disabled freedom, i.e., a pathology of freedom. Here then in these dangerous, difficult and demanding times, I revisit the insights of Nana Fanon’s liberation psychology and what I read as his insistence that the only reliable remedy for this pathology of oppression is liberational resistance.

To have read Nana Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) in the original French or the translated English, especially The Wretched of the Earth, and to grasp and embrace his understanding of armed struggle; decipher and find useful concepts in his discussion of the interrelatedness of national consciousness, culture and struggle; uphold his commitment to the masses; and take up his challenge to create a new history of humankind and a new man and woman; was for the advocates of Us and other organizations in the Black Liberation Movement of the 60s a central set of criteria for revolutionary consciousness and commitment. In this the month of his coming-into-being, July 20th, we are especially reminded of the complex richness and current relevance of Nana Fanon’s thought, but also its contribution, along with other key African activist-intellectuals, to the grounding and development of our own philosophy, Kawaida.

Fanon was born in Martinique, did his academic work for his doctorate in psychiatry in France and his professional work in Algeria, joined the Algerian Revolution, served as ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Revolutionary Government, and traveled throughout Africa representing and building support for the Algerian Revolution and the consolidation of pan-Africanism as a real and revolutionary practice. He wrote extensively on his experience and understanding of colonialism, crystallizing and summing up many of his most important observations and findings in his world-renowned masterpiece, The Wretched of the Earth.

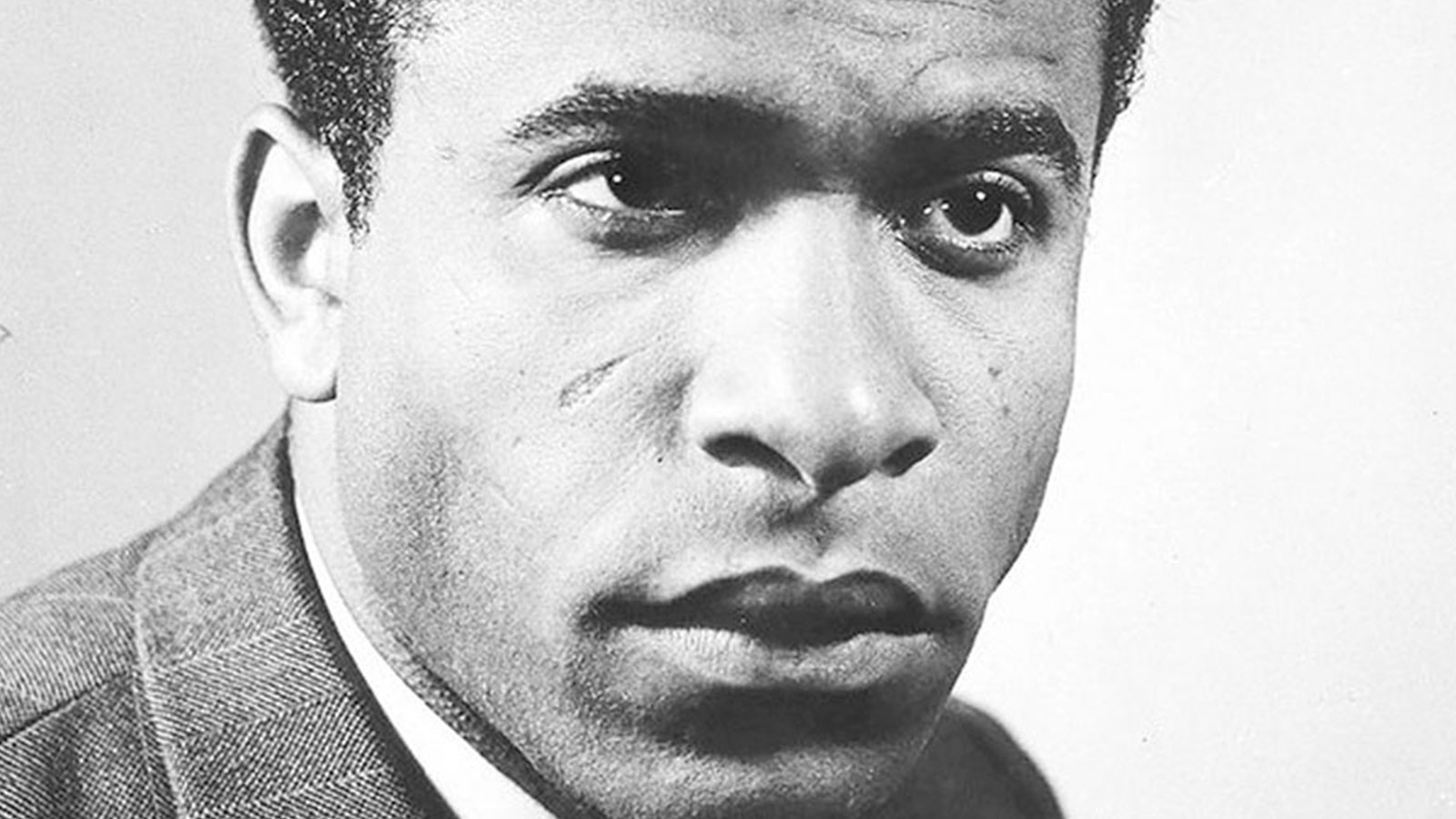

Franz Fanon

The ethical grounding of his social psychiatric theory and therapy is in a moral anthropology, a conception of the human person, in which human freedom, agency and struggle are normative and necessary and indispensable to the health, wholeness, and flourishing of persons and peoples. Within this critical understanding, he asserts as a fundamental proposition of his liberation psychology that psychopathology, the sickness of the psyche, is essentially “a pathology of freedom,” i.e., a socially generated problem, as well as a behavioral and organic one, rooted in oppression and unfreedom. A pathology of freedom speaks to the denial and the deforming and destructive limitation on human freedom and therefore, on human agency central to self-understanding and self-assertion in the world.

A psychiatrist and revolutionary, Fanon challenges and discredits the notion that a person can be isolated and understood apart from his/her social context. And he argues that the conditions of oppression affect both a person’s and a people’s conscious and unconscious thought and practice. Here, he evolves a second fundamental proposition that oppression, in this case colonialism, has a “totalitarian character,” and involves not just the conquest and occupation of lands, but also the lives of the people “settling at the very center of the individual” and engaging in “a sustained work” of depersonalization, deculturalization and dehumanization of the dominated people.

He speaks of a “sustained work of clean up or expulsion of self, of rationally pursued mutilation” of the African self and sense of self. Continuing, he says, “There is no occupation of territory, on the one hand, and independence of persons on the other. It is the country as a whole, its history, its daily pulsation that are contested, disfigured, in the hope of a final destruction”. Indeed, he says, “under these conditions, the individual’s (very) breathing is an observed, and an occupied breathing”.

Thirdly, Fanon argues that the colonized or oppressed person who is thus victimized and without the cultural resources or personal will to resist goes through several states of psychic debilitation and disintegration which I read as: including self-doubt, self-denial, self-condemnation and self-mutilation. Thus, he says, “Having judged, condemned and abandoned his cultural forms, his language, his food habits, his sexual behavior, his way of sitting down, of resting, of laughing, of enjoying himself, the oppressed flings himself upon the imposed culture with the desperation of a drowning man”. This person engages in shameless apish imitation of the dominant order, seeks security in submission and self-erasure in a series of dignity-diminishing and reality-denying ways, i.e., from individual acceptance fantasies to post-racial illusions eventually becoming what Fanon calls an “obscene caricature of Europe”.

Fourthly, Fanon asserts that at the heart of the prospects for rehabilitation and recovery is the concept and practice of agency, i.e., the ability and will to act in liberating and liberated ways, as this is translated in Kawaida philosophy. Therefore, he calls for both a collective responsibility of the people and a personal responsibility of each person in liberating herself and himself in the process of liberating the whole people. In a word, he says, “an authentic national liberation exists only in the precise degree to which the individual has irreversibly begun his own liberation”.

Finally, Fanon taught us the indispensability of transformative struggle on varied levels – armed, political and cultural. For Fanon, struggle is curative and transformative, empowering and liberating in a personal and social sense. It is in struggle that the people heal, renew and empower themselves by destroying the conditions of their disorientation and oppression. And he maintains, as we did in the Sixties, that these various battlefields form an interrelated and reciprocal, overarching field of struggle. Indeed, given the totalitarian character of oppression and its commitment to domination, deprivation and degradation on every level, Nana Fanon says, “the poverty of the people, national oppression and the inhibition of culture are one and the same thing”.

Thus, the aim of the struggle is not only political, the freeing of the country, but equally important, cultural, the freeing of each person’s consciousness from the ravages and restraints of colonization and oppression. In a word, the struggle is to realize “not only the disappearance of colonialism, but also the disappearance of the colonized man (and woman)”. Moreover, Fanon says to create a “national consciousness is the most elaborate form of culture”. Thus, the people “gather together the various indispensable elements necessary for the creation of a culture, those elements which can give it credibility, validity, life and creative power”. It is a culture which “ordain(s) the struggle for freedom,” affirms the best ideas and interests of the people and humanity, and expands in and through this transformative struggle.

Nana Fanon ends where he begins, calling for a new world, a new man and woman, and a new history of humankind. This, he maintains, requires a multidimensional struggle which stresses the centrality of the masses in their own liberation, and their grounding in their own culture, which is refreshed, renewed and expanded in struggle. And it is for him, a struggle directed toward ending the psychopathology and socio-pathology of oppression and toward advancing ourselves, humanity and history a step further and bringing the world to a whole ‘nother new and different level of human freedom, flourishing and possibilities in and for the world.