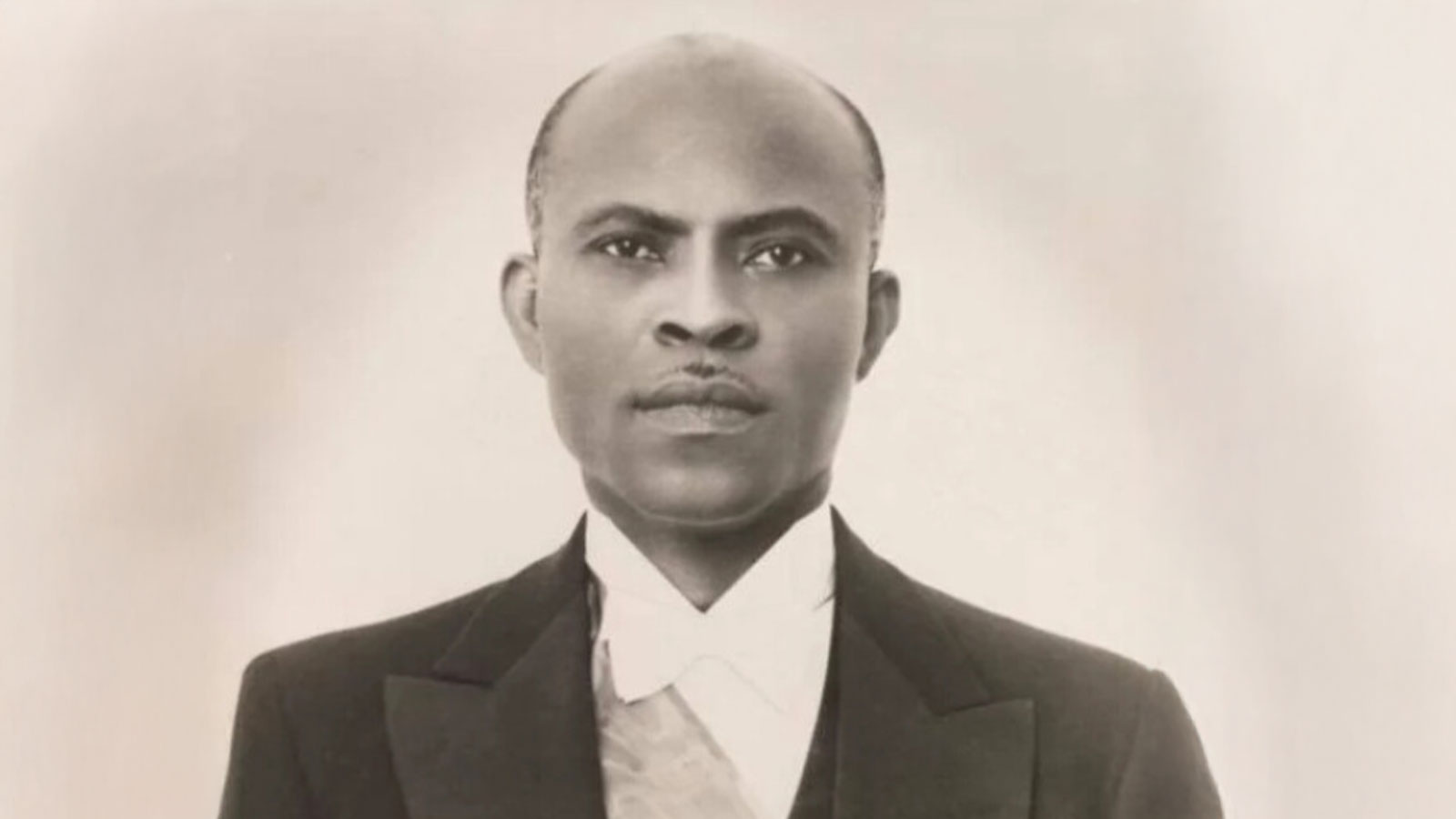

As the nation unravels today, the legacy of Haiti’s progressive president Estimé echoes louder than ever

It would be unreasonable to compare former Haitian president Dumarsais Estimé (1946-1950) to former French president Charles de Gaulle (1944-1946). The two men are not comparable, given the immense footprint the French general left in 20th-century political history—a resistance hero against Nazism, a military leader, a respected writer, a visionary statesman, and the voice of a nation in exile.

Yet, beyond their differences, both men belonged to the same era—one marked by major upheaval, global fractures, human tragedies, economic crises postwar restructuring and shifting political fault lines—they also held in common what de Gaulle himself, master in eloquent turns of thought, once described as “a certain idea of France.” Both were obsessed with national grandeur and driven by the desire to carve a place in history as leaders of their people.

On May 10, 1950, a military triumvirate composed of General Franck Lavaud and Colonels Paul Eugène Magloire and Antoine Levelt —forced Estimé to resign. The same trio had ousted President Élie Lescot just four years earlier during the “Cinq Glorieuses” uprising of January 1946. Ironically, the day before his forced resignation, Estimé had paraded through Port-au-Prince with those very men, waving to cheering crowds.

Estimé, affectionately known as “Titim,” had tried to sideline the officers by appointing them ambassadors abroad. They refused. From summer 1949 onward, he attempted to push through a constitutional change to seek a second term—a move supported by the Chamber of Deputies but opposed by the Senate and the military’s powerful core, led by Magloire, commander of the powerful Casernes Dessalines, who would later become president.

Politically isolated and squeezed by opposition parties, student groups and the military, and an unfriendly Senate—Estimé also faced pressure beyond Haiti’s borders. His decision to assert Haiti’s independence and identity—especially during the bicentennial exposition, angered Dominican strongman Rafael Trujillo, who ramped up a diplomatic assault that contributed to Estimé’s downfall.

The promise of a modern Haiti

Beyond the circumstances of his fall—already dissected by contemporaries, scholars and political commentators—what lingers most about Dumarsais Estimé is the political project he embodied. Despite its ideological limits and historical constraints, the Estimé presidency gave shape to a vision of modern governance that continues to haunt the Haitian imagination. His attempt to define the public good and build an independent Haitian state—one rooted in dignity and ambition—resonates all the more today, when measured against the collapse we now endure.

Estimé had already proven himself as a cabinet minister under President Sténio Vincent, overseeing public education, agriculture and labor. In his 1946 inauguration speech, he declared, “If we, the shepherds of the flock, become its wolves… if we betray our solemn commitments, the day will come when we must be judged and held accountable.”

Despite some authoritarian tendencies—closing opposition newspapers, banning political parties and trade unions, and aligning with U.S. anti-communist policy—Estimé led with a constant intent: to rebuild Haiti after the U.S. occupation through reforms rooted in social justice and nationalism. As the late historian Leslie Manigat described him, Estimé embodied the ideals of a “progressive nationalist,” born from the unrest and aspirations of 1946.

Concrete reforms, lasting impact

Few presidential speeches have resonated as deeply as Estimé’s March 25, 1947, address, in which he called on Haitians to finance their own freedom. His phrase “Heureux mécompte”—a fortunate miscalculation—became a rallying cry.

Estimé’s presidency, though short, saw landmark measures:

- In 1946, Estimé launched three new high schools and built about 40 rural schools. Teacher salaries in Haiti rose from 70 to 200 gourdes per month, equivalent to approximately $225 to $642 in today’s U.S. dollars. Girls gained access to secondary and university education. He established the École Normale Supérieure and the École Polytechnique and opened public libraries across the provinces. Top students earned study-abroad scholarships.

- 1946 Estimé founded and launched the National Coffee Office in 1946 to empower and support small farmers.

- In 1947, during a financial crisis, the U.S. refused to release Haitian reserves. Estimé responded by launching a national campaign. Within three months, Haitians of all backgrounds raised US $5 million in three months to reclaim control of the National Bank, freeing the country from debt obligations dating back to the 1800s.

- That same year, Haiti repatriated its National Bank from foreign control.

- In 1947, he laid the groundwork for the Péligre Dam. The construction began on the Péligre hydroelectric dam, completed in 1971

- In 1948, Estimé established the Artibonite Valley Development Organization (ODVA) with a $4 million loan to expand agriculture.

- From Dec. 8, 1949, to June 8, 1950, Port-au-Prince hosted the 1949-1950 Bicentennial Exposition, the only world’s fair held in Latin America or the Caribbean. It celebrated Haitian culture and launched a new era of tourism and showcased Vodou-inspired art. The exposition attracted more than 250,000 visitors—despite accusations of corruption and a staggering $26 million cost. Vodou entered the artistic mainstream. Naïve painting, West African-inspired music and popular art were celebrated.

- In 1948, Estimé inaugurated Belladère, a model town complete with modern amenities, to counter neighboring Elías Piña in the Dominican Republic. The border town later declined after Trujillo’s retaliation.

Legacy of dignity in an era of despair

The Bicentennial Exposition’s star power drew global attention. Artists such as Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Marian Anderson and Celia Cruz performed; art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York adorned public squares. Under the design of New York architect August Ferdinand Schmiedigen, theaters, casinos, cinemas and museums were built. But the extravagance came at a price—$26 million

Diplomatically, Estimé elevated Haiti’s voice. Ambassador Emile Saint-Lot helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and was the first to read it publicly. Saint-Lot also cast the decisive vote to establish Israel and later, Libya’s independence.

Allegations of embezzlement, especially the rumored disappearance of $10 million, turned public sentiment. Critics accused Estimé of squandering the nation’s limited resources on spectacle while urgent needs went unmet. Yet, in that moment, Port-au-Prince became a cultural capital, and Haiti emerged as a destination. Tourism flourished, energizing hotels, artisans and artists alike.

When he landed in New York on May 15, 1950, five days after the coup, his family deposited $70,000 in savings. His pension was set at $300 per month. That modest sum symbolized a leader who governed with integrity, despite the political battles that consumed his presidency.

I still remember the quiet dignity of Estimé’s sons, Paul and Lionel, in the neighborhood of Pétion-Ville. Friends of my family, they lived without extravagance until their deaths—an echo of their father’s values, grounded in humility and service.

Today, as Haiti reels from institutional collapse and relentless crises, Estimé’s name stirs a longing for vision and decency. While time must judge his leadership in full, the contrast with today’s dysfunction sharpens his legacy. Even Magloire, who helped remove him, tried to build on some of his reforms. In the national imagination, the period from 1946 to 1950 has come to represent a golden era—a rare moment when leadership felt tied to purpose, and when ordinary Haitians felt seen.

Seventy-five years after his fall, Dumarsais Estimé’s vision endures. We must ask why his name endures—often with admiration—long after so many others have faded. And perhaps what Haiti needs most today is for history to remind us of what is still possible.

Without romanticizing or retreating into nostalgia, perhaps the best thing that could happen to Haiti now is for history to call upon history.

Stéphane Pierre-Paul is a journalist native of Petit-Goâve, Haiti, with more than three decades of experience in the field. A founding member of the independent broadcaster Radio Kiskeya, he has served as reporter, news anchor, editor-in-chief, and now news director. He is also a linguist and a poet.

Source: Haitian Times