A Flawed “Model” Should Not be Used in the U.S. The “Truth” About South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Vantage Point Vignettes

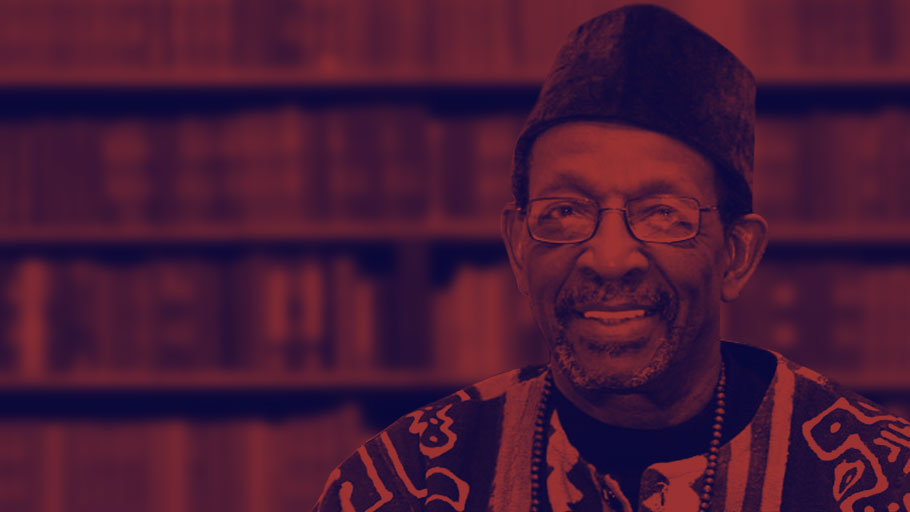

Comments and Commentary by Dr. Ron Daniels

As the quest for Reparations for African Americans is surging and the enactment of HR-40 is in site, there is concern among reparations advocates that the concept of “reconciliation,” popularized by the world renowned process adopted in South Africa, will be viewed by some as an acceptable alternative. First introduced in 1989 by the late Congressman John Conyers, the original bill was simply designed to establish a commission to “study” whether restitution for enslavement was warranted. The bill was a useful tool that reparations advocates utilized to create greater public awareness, support and the endorsements from numerous organizations and leaders.

However, in 2015 at the Request of the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC) and the National Coalition for Reparations for Blacks in America (N’COBRA), HR-40 was changed from a mere study bill to a remedy bill. Inheriting the torch from Congressman Conyers, under the leadership of Lead Sponsor Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, the revised bill will establish a Commission to study and develop reparations proposals for African Americans; not just to study, but to actually utilize decades of data and information to formulate proposals to repair generations of damages suffered by Africans in America as a consequence of enslavement and the derivative racially-exclusionary policies and practices after Emancipation to the present. This is the bill which is on the verge of being enacted by act of Congress or Presidential Executive Order.

But, as demand for reparations around the country grows louder and HR-40 moves closer to the goal post, there has been an intensified push for “reconciliation” type proposals to address the long history of racial oppression and exploitation of African Americans. Real “truth telling” about this horrific history of systemic racism is the pathway to “reconciliation. There is a popular assumption that the truth and reconciliation process healed the deep and painful scars of the brutal apartheid system in South Africa. The image of long suffering and resilient Black folks who are willing to forgive their oppressors has a compelling appeal to some liberal allies of the Black freedom struggle. Some Black folks are even enamored with this idea. I’m certain that the revolutionary psychiatrist Frantz Fanon and today’s African-centered psychiatrists and psychologists would beg to differ. And the truth is that increasing numbers of South Africans view the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a flawed process.

I address this matter in my book Still on this Journey: The Vision and Mission of Dr. Ron Daniels in an article entitled The Passing of Mandela and the Unfinished Freedom Struggle in South Africa:

In the face of fierce and unrelenting resistance inside the country and internationally, after 27 years, February 11, 1990, the illicit regime in South Africa was compelled to free Madiba, Nelson Mandela, the courageous leader and symbol of the movement for freedom, democracy and economic elevation of the masses of South Africans! What a memorable day. It seemed that the whole world watched as Mandela strode, tall, proud and confident out of the gates of imprisonment with Winnie Mandela at his side.

Now Mandela and the ANC were faced with the daunting task of transforming a resistance movement into a governing Party and to navigate a risky path of negotiating an agreement with the National Party that represented the White minority. While the ANC had a military wing that had engaged in armed struggle, its forces were far too weak to seriously threaten the vastly superior might of the South Africa security forces, whose ultimate mission was to protect the economic interests of the elite. Under these circumstances, Mandela led the way in encouraging a “truth and reconciliation” process which essentially allowed those who had committed crimes against humanity to confess their transgressions in exchange for immunity from prosecution (persons with the resistance forces were also requested to confess their transgressions). The National Party was also provided certain constitutional guarantees to protect the political interests of the White minority.

While we might debate whether this was a wise decision, the truth is that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was a concession, a compromise that paved the way for Black majority rule with the ANC ascending to power and Mandela to the office of President. Perhaps, this was the best short-term outcome that could have been negotiated given the imbalance of military power between the military wing of the ANC and the Armed Forces of the Apartheid regime. But it was a concession that would not actually heal the trauma resulting for generations of racial oppression or provide economic justice for the stolen labor that created vast wealth for the White minority!

The growing crescendo of discontent with the results of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which I heard first hand during my visit to South African with a Door of Return to Africa Delegation in 2019, is echoed in moving interview in the New York Times conducted by David Marchese with Professor Pumla Gobodo Madikizela. She served as a psychologist for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and is currently on the Faculty of Stellenbosch University. The article is entitled: What Can America Learn From South Africa About Healing? The following answer in response this question from Mr. Marchese is quite revealing:

Does that suggest that any real reconciliation would have required more of an economic-reparations aspect? “Absolutely. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission did bring the country together. The point that I’m making is that we made it too easy. You tell your story, the other person is moved and we express a sense of forgiveness. Which is great. I’m not undermining that. There is suffering, but at the same time we needed to do something to mitigate the impacts of this pain. This is where addressing economic injustices comes in. That didn’t happen at the right time, and now it’s not happening. The language of reconciliation is limited when used in isolation from other critical issues of social justice. Some things have changed. I mean, I am a professor at a university. But the structural problems still do exist.”

[ Read What Can America Learn From South Africa About National Healing? By David Marchese ]

The truth is what we can learn from the South African experience with “healing” by way of their Truth and Reconciliation Commission is that reparations must come first. There can be no reconciliation without reparations! Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee has correctly suggested that reparations are intended to eradicate systemic racism in this country. HR-40 is the umbrella policy prescription which has the potential to address white supremacy and structural, institutional racism and lead to reconciliation. The push for reconciliation, no matter how well meaning, must not detract from the strategic objective of enacting HR-40.