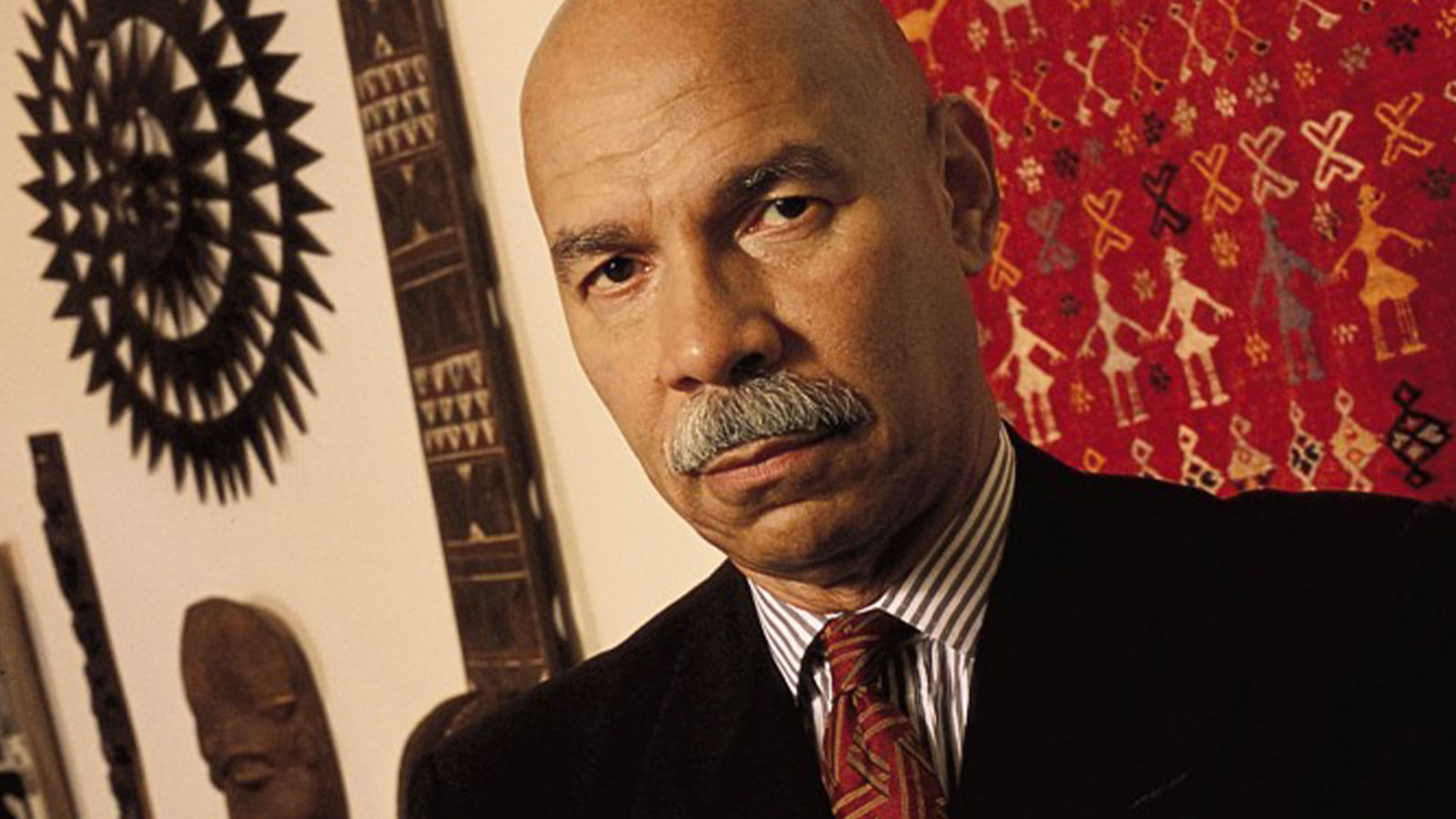

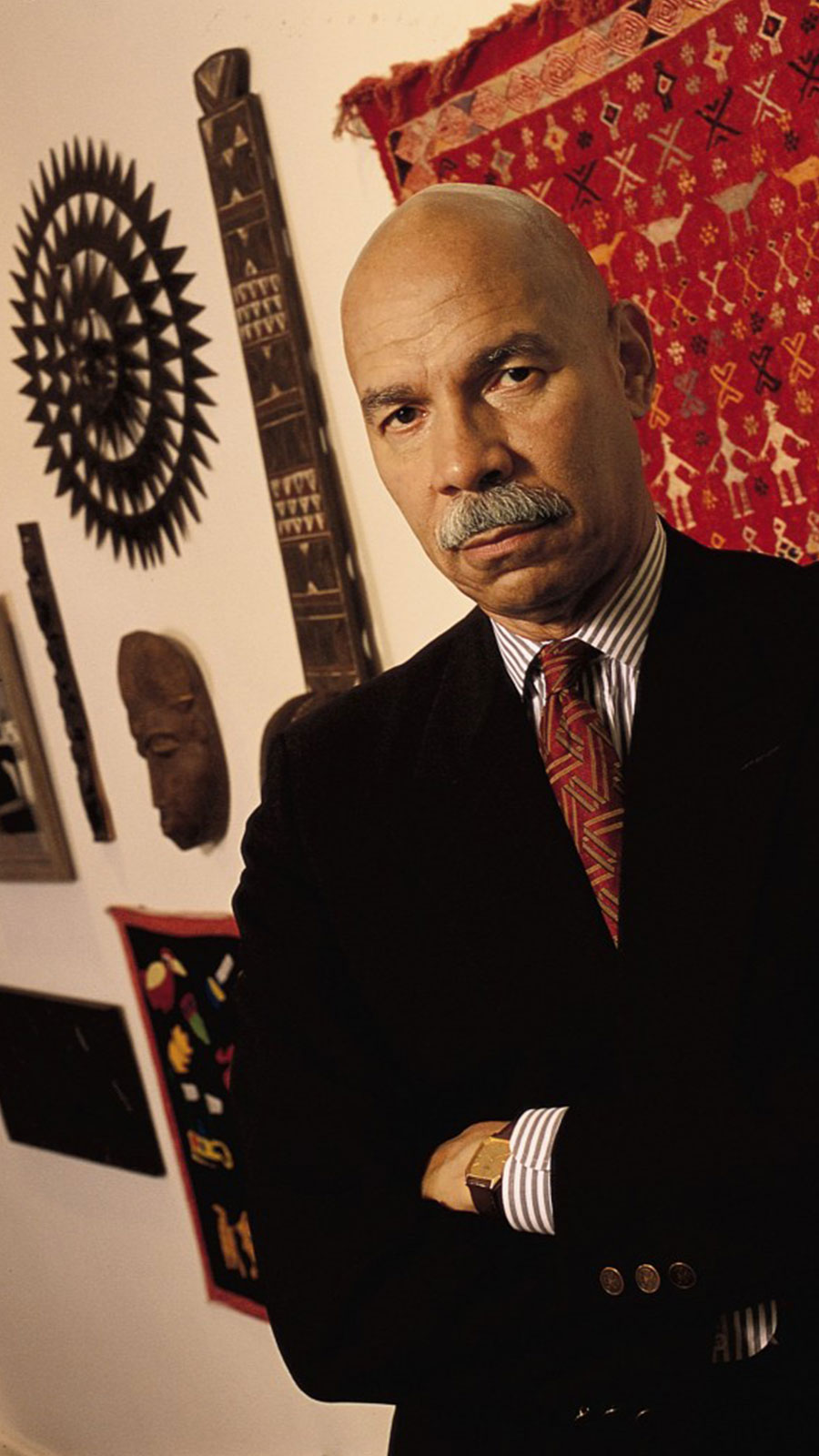

When a notice appeared that Randall Robinson, the exemplary human rights activist, law professor and man of letters had transitioned, journalists around the world recalled his unimpeachable commitment and global influence, many of their voices gathered on Journal-isms where the esteemed editor Richard Prince is at the helm.

On Saturday, as word spread of Robinson’s demise, James Hudson of TransAfrica, the platform established by Robinson in 1977, told Journal-isms that Robinson had been hospitalized in St. Kitts where he died on Friday morning at 81. According to Hazel Ross-Robinson, his wife, the cause of death was aspiration pneumonia.

Randall Robinson (July 6, 1941 – March 24, 2023)

Given his prominence as an activist, information about him from Historymakers to Encylopedia.com is available, where it is noted he was born July 6, 1941 in Richmond, Virginia. After attending Norfolk State College and Virginia Union University, he was a student at Harvard University in 1970, when his older brother Max began to gain national attention as a newscaster (He died of AIDs in 1988). Rather than pursue a more lucrative path in corporate law, Robinson, with his law degree intact, ventured to Tanzania on a Ford Fellowship and then returned to Boston to work as a lawyer for a legal aid project.

It was here that he began to fulfill his mission to live a principled life. In 1975, he was an aide to Rep. William Clay of Missouri, and a year later an administrative assistant to Rep. Charles C. Diggs, Jr. of Detroit where he was critically involved in a congressional trip to South Africa. This exposed him to a more intimate view of apartheid and almost immediately began thinking of ways to extend the advocacy spirit of the Congressional Black Caucus. As executive director of the newly formed TransAfrica, Robinson instituted programs that challenged President Ford’s “policy of tolerance toward white rulers.”

Within five years the group had grown exponentially and morphed into the TransAfrica Forum, the research and educational affiliate of TransAfrica, thereby expanding its global policy of education and publications. “You don’t change policy under the presumption that you must have a majority opinion on your side,” he told Black Enterprise. “In the final analysis, you need to organize a critical mass of people, which is not necessarily the majority of the Black community.” By 1984, some elements of that critical mass were evident. That was certainly the case two years later when TransAfrica, aided by other groups, pushed the U.S. Senate to override President Reagan’s veto to pass a series of sweeping sanctions against South Africa. In effect, this launched the Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.

Six years later, with TransAfrica applying additional pressure, was instrumental in more dramatic reforms in South Africa, several of which led to the first free and fair multiracial elections in the spring of 1994. Bringing about change in South Africa was just one of several crucial issues on Robinson’s agenda. He planned a hunger strike in protest of President Clinton’s policy on Haiti of stopping Haitian refugees at sea and returning them to their homeland. The Clinton administration vowed not to be influenced by Robinson’s defiance, but many believe Clinton finally capitulated after the activist’s nearly month-long fast, which eventually led to his hospitalization.

As Robinson struggled during the fast, the White House offered no comment on his worsening condition. Meanwhile, Robinson’s second wife was constantly at his side. “It is difficult to watch the one you love deprive himself of one of the most basic human activities to sustain life and maintain health,” she told reporters. She said she had never tried to discourage him because “I think it is a just cause.” In An Unbroken Agony, Robinson writes of this ordeal and the Haitian experience at length.

Out of the hospital, Robinson renewed his commitment to other human rights issues, particularly in Ethiopia, Kenya, Zaire, and Malawi. In 2000, reparations was a chief concern and his book The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks gave the cause additional resonance. He followed this popular publication with Reckoning: What Blacks Owe Each Other. Here the ever insightful Robinson flipped the script as he examined crime and poverty in urban America at the same time urging Black Americans to intensify the quest for social and economic success. Other topics discussed included ramifications of the prison industrial complex.

To some extent this was a harbinger of his passing the baton of struggle to the next generation and by 2001 he relinquished his leadership of the two groups he founded. Disgusted with the persistence of racism and discrimination in America, he moved his family to the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, Hazel’s home. “America is a huge fraud, clad in narcissistic conceit and satisfied with itself, feeling unneeded of any self-examination nor responsibility to right past wrongs, of which it notices none,” he explained to reporter Ellis Cose of Essence why he left America. He elaborated on this point in 2004 in his book Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land. His other books are The Emancipation of Wakefield Clay: A Novel and Defending the Spirit: A Black Life in America.

Robinson’s last book was Makeda, which Essence magazine described as a “hypnotic” novel about the bond between a remarkable Black matriarch and her grandson. It was published by Open Lens, an imprint started by three Black women who were determined to get the book published.