By Herb Boyd —

It was almost a year ago that Arizona State University named its film school after Sidney Poitier. They enshrined him before the ages claimed him. Poitier, the pioneering actor and author, died on Friday, January 7, according to Fred Mitchell, a close family friend, and minister of foreign affairs of the Bahamas. Among a collection of firsts, most notable was his achievement as the first African American to win an Oscar as Best Actor in 1963 for his role in “Lilies of the Field.”

That his death was confirmed by the Nassau Guardian and Mitchell was affirmation of the islands where he grew up, though he was born in Miami, Florida. He served as a non-resident Bahamian ambassador to Japan from 1997 to 2007 and for this exceptional honor was knighted as Sir Sidney. The western bridge that connects New Providence to Paradise Island is named in his honor.

At the beginning of his illustrious acting career he had to overcome his Bahamian accent. “I had this horrible accent,” he wrote in his autobiography “This Life” (Alfred Knopf, 1980). “Well, I had to rid myself of the accent and I had to learn to read well. How do you rid yourself of an accent? I asked myself. I decided the best way was to listen to the way Americans speak, and to copy it… The best thing was to get me a radio. That very same day I went back to the want ad section of the Amsterdam News and picked out a dishwashing job. Out of the first week’s salary, I bought a thirteen dollar radio. For the next six months…I listened to that radio morning, noon, and night. Everything I heard, I would repeat it, it didn’t matter what it was….”

Perfecting his English and pronunciation brought him an assignment delivered to him by Frederick O’Neal, once he became a member of the American Negro Theater (ANT) at the Schomburg Center. It was also from reading the Amsterdam News that he saw the ad seeking actors for a little theater group. This part of his journey to the world of film followed his birth in Florida on Feb. 20, 1927, his coming of age on Cat Island in the Bahamas, completing a short but rough stint in the military, and arriving in New York City for the second time in 1944.

It was during these emerging stages of his career that he encountered Harry Belafonte, and in the beginning things did not go well in their competition as actors in the American Negro Theater. One day when Harry failed to show up for a role in which Sidney was the understudy, it was a propitious opening. “Once Sidney and I got past that rough introduction, we started hanging out together,” Belafonte recalled in his memoir “My Song” with Michael Shnayerson, (Knopf, 2011). “This was more than a casual new acquaintance for me. Sidney was my first friend—my first friend in life.”

His training at ANT was rewarding and after a failed first round––mainly because he was tone deaf and unable to carry a tune––he succeeded in landing a role in the Greek comedy “Lysistrata,” in which, despite its short run, his performance was noteworthy. When he chose to leave the stage and take a role in “No Way Out” (1949) where he was in racist conflict with a character portrayed by Richard Widmark, he was on his way to bigger and better parts, including “Cry, the Beloved Country” with his Black predecessor on screen, Canada Lee. But he really made his mark in 1955 in “Blackboard Jungle.”

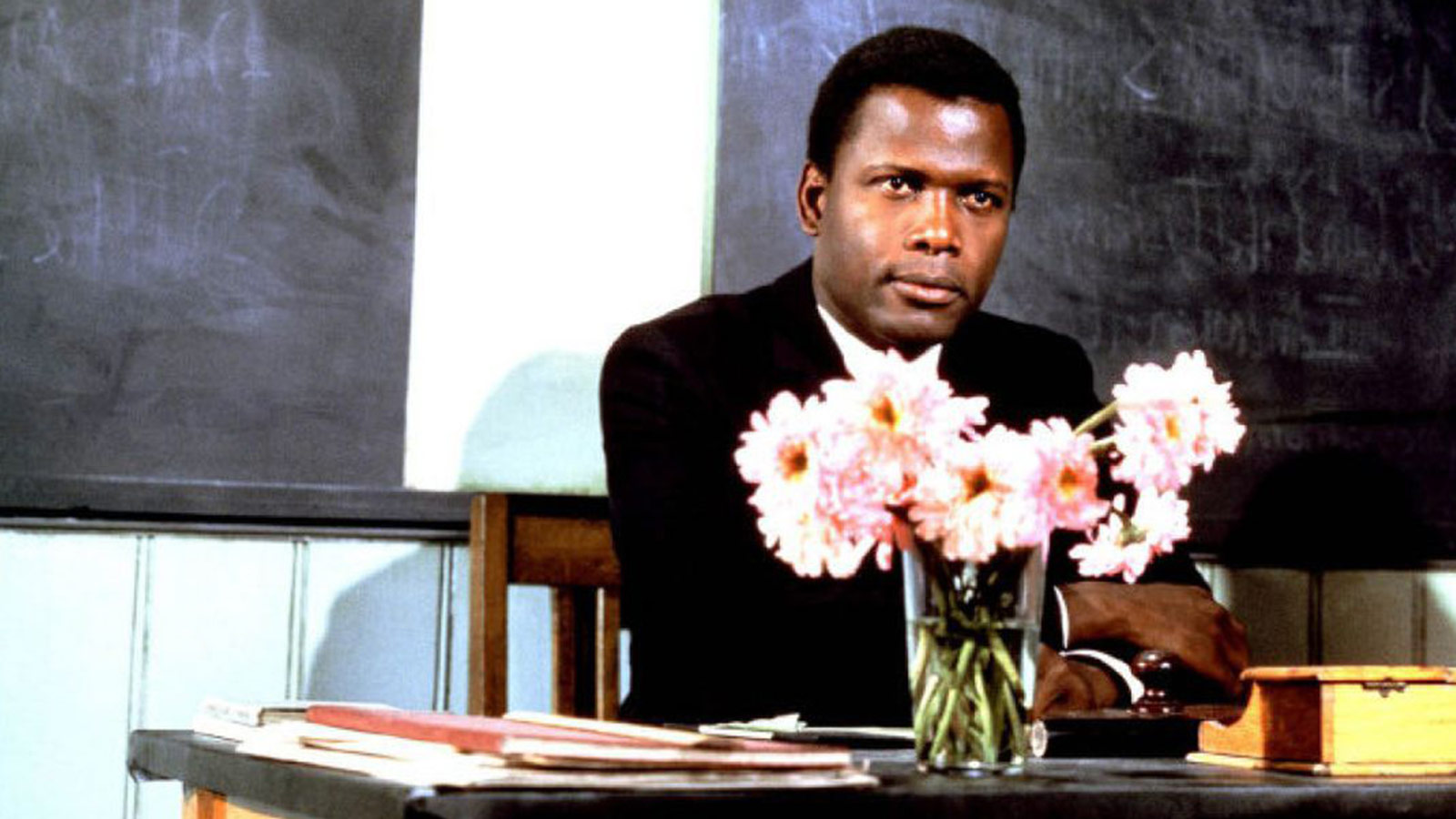

Three years later he starred with Tony Curtis in “The Defiant Ones,” another film where racial tension was the central theme. Both actors were nominated for Best Actor, a first for Sidney and Black Americans. In 1959, he began a succession of highly regarded films—“Porgy and Bess” (1959), “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), and “A Patch of Blue” (1965.) Of course his Academy Award winning performance was in “Lilies of the Field” in 1963. The problems of race were highlighted in such films as “To Sir, with Love” (1967), “In the Heat of the Night” (1967), and his unforgettable words of “they call me Mr. Tibbs.” Topping off this banner year for him was “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” with the formidable duo of Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. “Buck and the Preacher” (1971) was an opportunity for him to showcase his directorial skills, thanks to the tutoring of William Wellman. It also put him on screen with his lifelong friend Belafonte. The film came at a time when Blaxploitation films were commanding wide attention, if not praise.

So when Sidney was offered another chance to direct, Belafonte cautioned him against such a move but eventually signed on to him with “Uptown Saturday Night,” which was so successful that two sequels followed—“Let’s Do It Again,” and “A Piece of the Action,” and getting Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor as characters certainly didn’t hurt him at that box office.

Citing each movie in Sidney’s filmography would consume this space to say nothing of the documentaries in which he was a key figure as informant or narrator. Beyond the realm of cinema, Sidney was often a prominent citizen for civil and human rights, and he participated in several fundraising events, one of them a harrowing venture into Mississippi thanks to being induced to do so by Belafonte.

After his marriage ended with Juanita Hardy (1950-65), and after a nearly ten-year affair with actress Diahann Carroll, he married Joanna Shimkus. He had four daughters with Juanita (Beverly, Pamela, Sherri, and Gina) and two with his second wife (Anika and Sydney).

Almost as extensive as his filmography are the honors and awards—a Grammy, two Golden Globes, and a British Academy Award. There was an AFI Life Achievement Award and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1994. He was a Kennedy Center Honor in 1995 and in 2009 President Obama presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Earlier, in 1974, he was saluted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth.

“We have lost an icon, a hero, a mentor, a fighter, a national treasure, and” said the Bahamas Deputy Prime Minister Chester Cooper. “I was conflicted with great sadness and a sense of celebration when I learned of the passing of Sir Sidney Poitier.”

And these sentiments are sure to be part of a groundswell of recollections and tributes.