The 50th anniversary of the assassination of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (Malcolm X) came and went on Feb. 21 of this year. And just as in other years when the date of Malcolm’s assassination came around, his name trended for a few hours and then the stifling silence rolled back in, erasing his name from the social media landscape almost as quickly as it had re-emerged.

This year the occasion didn’t go completely unacknowledged, and some would even say that Malcolm was recognized in all the ways that mattered. There was massive coverage of the occasion right here at The Root, as well as other sites geared to black audiences. There was a CNN special that gave us a glimpse into the last moments of Malcolm’s life via the people closest to him that day. And the Shabazz Center organized a spectacular program in his honor—with a diversity in the ethnic, racial, religious and cultural DNA of the crowd in attendance that was a powerful reflection of the man himself.

But we need to do more to remember Malcolm. And we could do more this weekend, when all eyes turn to Selma, Ala., to recognize the 50th anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” massacre that took place on March 7, 1965, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

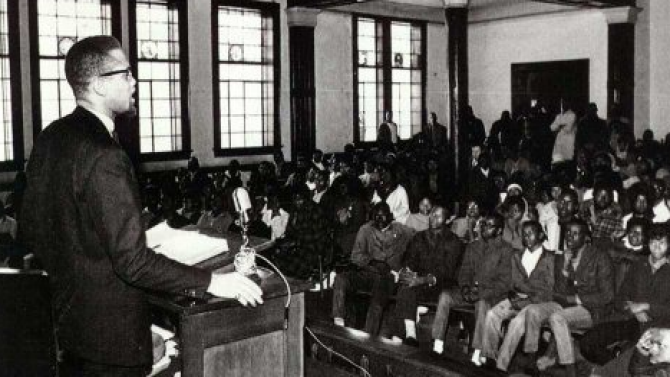

Malcolm’s presence in Selma on Feb. 4, 1965, 17 days before he was assassinated, is not often talked about. Martin Luther King Jr. was in jail in Selma at the time, and Malcolm was invited by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to make it plain for the young civil rights activists as only he could.

Speaking from behind a podium at Brown Chapel AME Church, Malcolm compared the “house Negro” and the “field Negro” and talked about the importance of not becoming complacent in “massa’s house” or comfortable with the status of being an oppressed people. Even before making the trip down South, and after seeing King get knocked down by racists on television that January, Malcolm had written to George Lincoln Rockwell, head of the American Nazi Party, and told him that the days of turning the other cheek were over.

After being told that Malcolm had addressed the crowd that day in Selma, Coretta Scott King said that she was asked by King’s aide Andrew Young—who went on to serve as a congressman, mayor of Atlanta and the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations—to calm the crowd, but she refused. Instead, Coretta Scott King had a brief heart-to-heart conversation with Malcolm that changed her perception of him.

In Scott King’s 1988 Eyes on the Prize II interview with Jackie Shearer, she said the following about Malcolm:

He leaned over and said to me, ah, “Mrs. King, I want you to tell your husband that I had planned to visit him in jail here in Selma, but I won’t be able to do it now. I have to go back to New York, ah, because I, I have to attend a conference in Europe, an African student conference, and I want you to say to him that I didn’t come to Selma to make his job more difficult, but I thought that if the white people understood what the alternative was that they would be more inclined to listen to your husband. And so that’s why I came.” … And of course within about a couple weeks or more he was assassinated, and it affected me very deeply … for days I had this pain, almost like this feeling in my chest, a feeling of depression, and, ah, just feeling as if, ah, I had lost someone very dear to me, and I, you know, I couldn’t quite understand, but then I began to realize, ah, I guess what an impact he had made on me in that very short period of time in knowing him.

Perhaps most importantly, Scott King said that she believed that Malcolm X would have been a “tremendous bridge” and that he and King would eventually have been unified in purpose: “I think if he had lived, ah, and if the two had lived … I am sure that at some point they would have come closer together and would have been a very strong force in the total struggle for liberation and self-determination of black people in our society.”

That moment is now.

The movements for which King gave his life, and the fight for human rights for which Malcolm X gave his, have merged. Key pieces of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 have been dismantled. Police officers are gunning down unarmed black men and women and rarely face repercussions. Politicians tap-dance during election season, but it’s going to take more than pretty words and political pandering to sway today’s activists—no matter how many of them show up in Selma this weekend to march.

During #MX50Forever, Democratic New York state Sen. James Sanders said that the spirit of Malcolm X is everywhere, flowing freely through the #BlackLivesMatter movement. “I saw him in Staten Island; I saw him in Ferguson. Anytime a young person does something to rebel, Malcolm is alive,” Sanders said.

A month before the pivotal attempt to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Malcolm said to that intent crowd in Selma:

I pray that God will bless you in everything that you do … I pray that all the fear that has ever been in your heart will be taken out, and when you look at that man, if you know he’s nothing but a coward, you won’t fear him. If he wasn’t a coward, he wouldn’t gang up on you. He wouldn’t need to sneak around here. This is how they function. They function in mobs—that’s a coward. They put on a sheet so you won’t know who they are—that’s a coward. No! The time will come when that sheet will be ripped off. If the federal government doesn’t take it off, we’ll take it off.

Whether or not it’s ever said, the spirit of Malcolm X—his life, his teachings, his assassination—was also stirring on that bridge in Selma on a bloody Sunday in 1965. And it’s only right that he be recognized.

Kirsten West Savali is a cultural critic and senior writer for The Root, where she explores the intersections of race, gender, politics and pop culture. Follow her on Twitter.