As Cuban President Raúl Castro stepped down from office today, Cuba is expected to enter a period of dramatic change. Eager to witness the final days of the nearly six decades of Castro rule in Cuba, my son and I recently visited the island nation. We were provided a view of a communist country marked by profound continuities and changes in Cuban culture, the arts, and technology.

We arrived on February 20, while a Congressional delegation headed by Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont was there meeting with Castro, Cuban ministers, entrepreneurs, and ambassadors from several foreign countries. The delegation held meetings regarding the presidential transition, immigration, diplomacy, and new US Treasury Department regulations which re-impose travel restrictions on US citizens visiting Cuba. Travel restrictions had been reduced in 2016, when Obama made a historic visit to Cuba, meeting with Raúl Castro.

Under President Trump, however, US policy has returned to pre-Obama restrictions. As a result, American tourism to Cuba has plummeted, and US citizens are again far outnumbered by Canadian and European visitors. Those wanting to travel directly from the US – as opposed to going through Canada or Mexico – must obtain a visa and check one of 18 boxes explaining the purpose of one’s travel. These include family visits, official business, educational activities, humanitarian projects, and “support for the Cuban people.” We checked the “journalistic activities” box.

As our departure date approached, my son and I were warned by experts on the country and a Cuban expat who used to work for the University of Havana that we would need to be very careful in how we conducted ourselves there. They explained that foreigners – especially Americans – must obtain a journalistic visa from the Cuban government to conduct journalistic activities and that people we interview there could also get in trouble for talking to us. They advised that since there was no time to obtain a journalistic visa we should pose as tourists and avoid asking political questions, especially in public places. They further warned that many Cuban residents will report “suspicious” activities.

We took their advice and determined we would report on contemporary Cuban culture, the arts, and technology. These turned out to be excellent choices: they opened doors that revealed fascinating aspects of Cuban life. And, sure enough, when we did broach political questions, nearly everyone we spoke with clammed up.

“I can speak whatever I want but not so much that can get me into trouble or in prison,” one musician we interviewed explained. “In Cuba you can go to prison for ten or fifteen years if you say something bad about the Cuban revolution. You cannot go to the Plaza de la Revolución and shout ‘Down with Castro brothers,’ because you’re risking to get imprisoned.”

Having traveled to Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and several other Caribbean countries, we were totally unprepared for the culture shock we experienced on our first visit to Havana. With its vintage cars, colonial architecture, and communist government, in many ways Havana appears stuck in time some 50 years ago. Yet there has been some significant change over the past several years and, with Raúl Castro stepping down, the pace of change may be poised to accelerate.

Over 90% of the ubiquitous, well-maintained, vintage American cars in Havana are taxis. Photo by Daniel Winthrop

A major economic change, which started around 2010, has been the slow introduction of free enterprise. This started with Cubans being allowed to own their own taxis, casa particulars (B&Bs), and small restaurants. With the government typically paying doctors, lawyers, professors, other professionals, and government workers between $20 and $40 USD a month, these small-time entrepreneurs can earn far more. Indeed, many doctors, lawyers, and others have quit their jobs to open restaurants, B&Bs or operate taxi services, car repair shops or other small businesses. Most other government employees moonlight to break out of their subsistence lifestyles.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had offered major financial support to the island, oil-rich Venezuela under Hugo Chávez stepped in to fill the gap. But when the price of oil plummeted in 2008 it hurt the Venezuelan economy and had a ripple effect on Cuba. And the global recession of 2008-09, while it didn’t impact Cuba as directly as most western countries, only made matters worse.

A that time, “the government told 800,000 people, ‘Sorry, we don’t have jobs for you but you can open your own business,’ what they call the private sector,” according to one Cuban we spoke with.

While quality health care and education are free, the majority of Cubans are very poor and live hand-to-mouth. Many agricultural workers make only about the equivalent of $5 a month. An elderly couple we met on the street invited us to visit their tiny, squalid apartment next door to a tourist restaurant featuring Ernest Hemmingway décor. They complained that the government told them 15 years ago they would be moved into a decent house, but they’re still waiting.

“Marc” (he asked we not use his real name so he could speak candidly), a Polish émigré musician who splits his time between London and Havana, spoke at length with us about his time in Cuba. When he first visited the country in 1999, after seeing Wim Wenders’ Buena Vista Social Club, he fell in love with the Cuban people. “How can I explain this?” he started. “Let’s say someone has a fridge and in it he has one sausage and one egg and nothing else. And say I invite you to this house, and this is his fridge. And he’ll give you his last piece of meat. He won’t even think about tomorrow. And you’ll think, ‘Oh that’s very nice,’ but you won’t know the truth is that you just ate his last piece of food. And this is something amazing.”

“Cubans have developed a sense of improvisation, of invention to help them survive – and a spirit of solidarity,” another European visitor we met observed “If you cannot get on your feet, they will help you.”

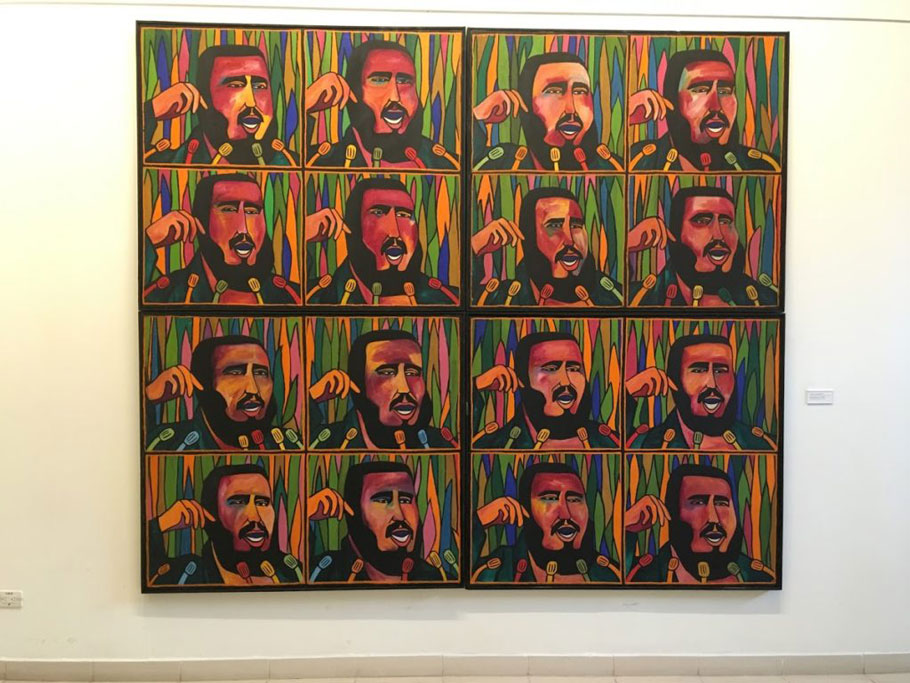

Oye America (1967) by Raul Martinez on display at Havana’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Arte. Photo by Daniel Winthrop

Havana has rich and thriving arts and music scenes. Carlos Miguel Ramos, a prominent drummer who has travelled the world with Rubén Blades and others, invited us to his family’s attractive house on the edge of Old Havana near the shore. Ramos comes from a family of performers. “Before the 1959 revolution my grandfather was a corporal in Batista’s army. Then he became a bass player; he played upright bass with Benny Moré – one of the greatest Cuban singers with worldwide recognition,” Ramos noted with pride. “My dad was a dancer in the Tropicana night club for ten years. My mother was also a dancer.”

“I do not have a state-paid job, because I would only be paid 30 CUCs [Cuban convertible pesos] a month and there is not much I could do with that money,” Ramos continued. One Cuban peso is roughly equivalent to one US dollar. “A kilo of chicken costs four CUCs, a bottle of oil costs three CUCs, a bag of powdered milk costs six or eight CUCs. And when you see that you only make 30 CUCs, you realize that you cannot buy enough food.”

“The lives of musicians, artists and sportspeople in Cuba are very difficult. We get good meals and money to get by, but it’s not enough to wipe your ass,” Ramos concluded. “We are not happy with the way the economic system operates in the country.”

Cuban art is an exceptionally diverse cultural blend of African, South American, European and North American influences. The Museo de Belle Artes Cubano contains a very impressive body of work, from the Spanish colonial period up to very recently.

“I don’t think there is a country that per capita produces more great art than Cuba,” explained Jorge Pérez, an Argentine-born son of Cuban parents and the author of On the Horizon: Contemporary Cuban Art.

In the early years after the revolution, because art was state sponsored, an implied censorship occurred; artists didn’t want to make art against the revolutionary movement that funded their work. But during the 1980s, Cuban art began to reflect more unfiltered expression, and since then modern art has experienced an impressive and dynamic revival. Recently the art scene has been reinvigorated by the emergence of a new generation of Cubans who didn’t experience the revolution directly.

Soon after our arrival, we met one such artist, a very successful photographer and teacher, Alfredo Sarabia. To sell their work for higher rates, Sarabia and many other artists cater mainly to tourists. Sarabia’s photos can fetch hundreds of dollars each. He says the Cuban Ministry of Culture respects Cuban visual artists, allowing them to mostly operate outside government control.

Young Cubans mingle with foreign tourists at the ultra-hip Fábrica de Arte Cubano. Photo by Daniel Winthrop

Foreign tourists and young Cubans alike frequent the Fábrica de Arte Cubano (Cuban Art Factory, FAC), an olive oil factory converted into an art gallery, performance space, and night club to experience a younger and edgier Cuban culture. Local teenagers who don’t have a lot of money can go dancing there from 8:00 – 4:00 am four days a week for a $2 cover charge. An average of 2,000 visitors visit the FAC nightly. A Trip Advisor reviewer called it “the hippest place I have ever been.” When we left at around 1:00 am, the line was longer than when we arrived at 8:00 pm.

Cuban musician X Alfonso founded the space four years ago. X Alfonso is a popular Cuban rocker and artist who manages to keep the place in operation without running afoul of Cuban authorities. The FAC is classified as a “community project,” allowing it to occupy government property but operate with a broad degree of independence. It has come under criticism in state media for appearing too much like a thriving, capitalistic enterprise, and some of its art pushes political boundaries.

“I really believe that Cuban artists have complete freedom in making their art,” 27-year-old assistant curator Lisset Alonzo told us, echoing the photographer Sarabia. “The idea here was to create a space where all the arts could be together: design, visual arts – a complete program that includes classical music, other kinds of music, dj programs, and also theater and dance.” The FAC’s mission is to rescue, support, and promote the work of thousands of Cuban artists of all art branches including music, dance, theater, visual arts, literature, photography, fashion, graphic design, and architecture. It rivals any gallery/performance venue that New York, London, or Berlin has to offer.

Another dramatic change Cubans are experiencing is through the internet, which became available to the general public less than three years ago in the form of Wi-Fi hotspots in a few public parks and other locations. At $1 – $2/hour, the web is incredibly expensive by Cuban standards and out of reach for many Cubans; Wi-Fi in private homes is strictly illegal. The government sees opening that world of multi-faceted ideas, opinions, and cultural phenomena as a threat – though many Havana residents we spoke with expect that to change very soon.

Facebook Messenger has also become quite popular in Cuba in the year or so that access has been available. Most other US websites are blocked. Some creative Cubans have gotten around the expensive connection fees by hacking into the system and sharing the connection with friends for a discount.

All internet service in the island nation is controlled by the state-owned telecom company ETSECA and primarily provided through roughly 237 crowded government-approved paid Wi-Fi hotspots around the country – not a lot of internet access for a country of 11 million people. According to the Miami Herald 37% of Cubans use Wi-Fi weekly – one of the lowest rates in the Western hemisphere; only a small percentage use it daily. Many Cubans credit Obama’s policies toward Cuba and his 2016 visit for the relaxation of government restrictions on the internet. After the visit, Raúl Castro pledged that Cuba would accelerate internet access for its citizens.

Cristo Parc, one of the many popular wi-fi (pronounced wee-fee) hot spots in Havana. Photo by Daniel Winthrop

“We want every person in Cuba to be able to be connected,” US Secretary of State John Kerry said when he was in Havana in 2015 for a flag-raising ceremony at the US Embassy. “We have offered to and we will help in every way possible to help provide that connectivity.”

However, where connection is possible, the speed is often so slow there is very little Cubans can do online but check email and surf sluggish websites. Some critics say Cuba has poor internet by design, to prevent most Cubans from accessing outside culture or information. In any case, the lack of wider access does limit Cubans’ commercial use of the net for income.

It’s common in Havana to see young Cubans – and foreign visitors – perched on park benches tapping at laptops, leaning against building walls or sitting on curbs staring at tablets or cellphones, chatting or sending selfies and other photos to friends and family abroad and around Cuba.

“People tell me, ‘I want to go to Cuba right now, before it changes,’” said Marc. “I heard this 15 years ago, and I heard it again two months ago. If you think this, don’t worry, Cuba’s not going to change for another ten years.” But he allowed that increased web access and lower prices could hasten the pace of change.

While we were waiting in line to visit the FAC, we met Yoan Serrats, a Spaniard visiting Havana to cast Cubans for a theater production to tour Europe. “It’s been 50 years of endurance and now Cubans want to live better and to open the doors a little bit more,” said Serrats. “But they don’t know if they are going to succeed, so they don’t want to let the doors wide open all of a sudden.”

“You can’t expect there will be fast change, that one morning you’re going to wake up into a new modern, democratic system. No,” Marc opined. “That’s what we did in Poland: I remember this very well, that overnight we changed the system and we woke up to a completely different world. At that time there was no textbook as to how we’re going to live, what we’re going to do. That was crazy.”

Added drummer Carlos Ramos, “The Cuban government will never die, never.”

A bust of José Martí, hero of the 1898-99 war of independence from Spain, is part of a popular cordoned off block of street art in the middle class Vedado section of the city. Photo by Daniel Winthrop

The newly elected National Assembly inaugurated on April 18 just nominated Cuban First Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel to be the unopposed candidate to replace Castro as president. Castro himself will remain head of Cuba’s Communist Party, still a very powerful position. The 57-year-old Diaz-Canel is expected to continue the communist legacy of the Castro brothers. “Imperialism can never be trusted, not even a tiny bit, never,” he recently said.

In a leaked videotape taken at a private meeting with Communist Party members last summer , Díaz-Canel lashed out against Cuban dissidents, independent media, and embassies of several European countries, accusing them all of supporting subversive projects and seeking to undermine the Castro government, according to Nora Gámez Torres of the Miami Herald.

Other Cuba analysts have speculated that Díaz-Canel’s sometimes moderate views will prevail. The few Cubans who commented to us about the impending leadership change said they feel that, in terms of the government’s crackdown on dissent and free speech, they expect things to get worse before the trend toward easing restrictions resumes.

When Díaz-Canel assumed the leadership of Cuba today, April 19, he praised the Castro brothers, pledged to resist any attempts by the US or other nations from subverting Cuba, and promised to continue “perfecting” the socialist model passed on to him after nearly 60 years of communist governance.

“The revolution continues,” he told Cuban state television.

Che Guevara’s giant image adorns the façade of the Cuban Ministry of the Interior in the Plaza de la Revolución. To this day Che is more visible and iconic in Havana than either Castro brother. Photo by Daniel Winthrop

By way of a footnote: on reentering the US in Charlotte, NC, my son and I were waived through customs in two minutes. When I asked if anyone wanted to see the itinerary we were told we had to keep as journalists, the customs official smiled, saying “Oh, you don’t need to worry about that.” Most US tourists traveling with us checked the box “Support for the Cuban People,” and were also told to keep an itinerary or journal, but nobody checked. Based on our experience, virtually anybody can freely travel to Cuba for any reason without fear of scrutiny.

Nat Winthrop is an independent film producer living in Montpelier. He is former publisher of the Vanguard Press and Vermont Times in Chittenden County, and he has had feature articles published in the Rutland Herald/Times Argus Sunday Magazine, Seven Days, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and Vermont Magazine. He studied documentary filmmaking at MIT and Goddard College in the 1970s. He was executive producer of the collaborative six-part Freedom & Unity: The Vermont Movie (2013) among other documentaries. He is also the Vice President of the Toward Freedom board.