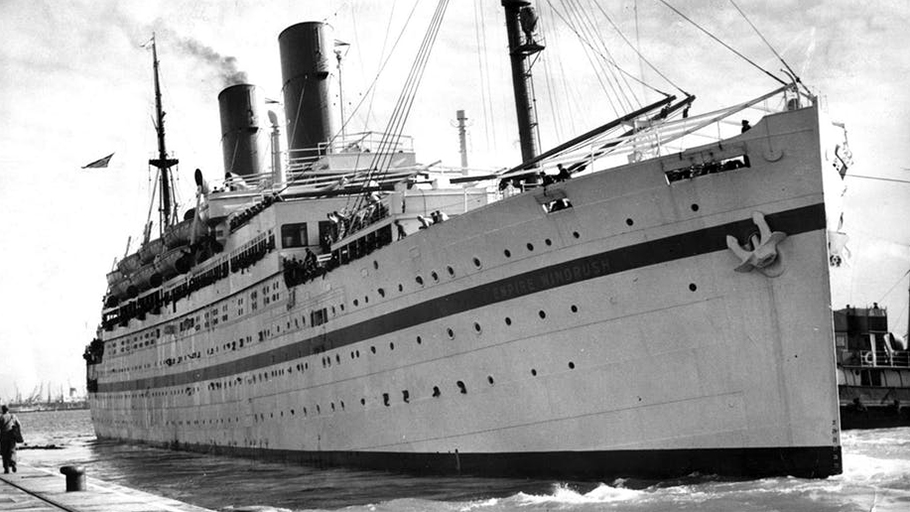

The Empire Windrush, photographed a few years after its famous journey from Jamaica to Tilbury Docks. PA Archive

By James Procter, The Conversation —

Amid the celebrations to mark the 70th anniversary of the arrival of Empire Windrush from the Caribbean in 1948, much has been made of the warm welcome that once greeted those migrant men and women in Britain’s hour of need, as postwar reconstruction got underway.

But it’s important Britain remembers that moment for what it was: a story of mixed reception.

Despite and because of its legendary status, the sources of information we now use to tell the story of the Windrush tend to be both highly selective and repetitive. But thanks to the BBC Written Archives, I’ve been able to study a curiously overlooked series of documents for BBC radio that scripted the ship’s reception at the time.

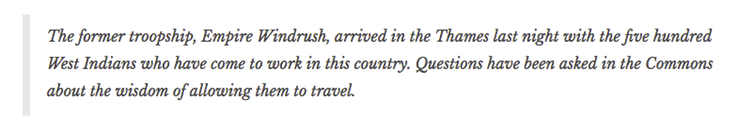

In contrast to the contemporary newspaper headlines typically gathered to commemorate the event – “Welcome Home” (Evening Standard), “Five hundred pairs of willing hands” (Daily Worker) – the BBC’s home service news bulletin offered a stark, even stern, summary of the ship’s arrival on the morning on June 22, 1948, mentioning questions asked in parliament.

Bulletins later that day referred to the 18 stowaways on board who were sentenced or fined accordingly.

Bulletins later that day referred to the 18 stowaways on board who were sentenced or fined accordingly.

Mood of the new arrivals

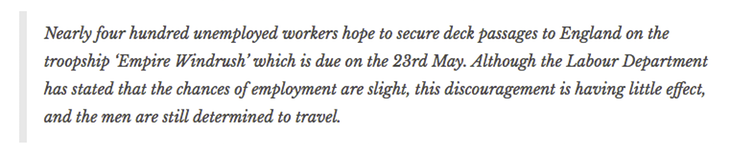

A month before the Windrush docked at Tilbury, “Calling the West Indies”, the BBC’s overseas broadcast from London to the Caribbean, captured the prevailing mood of the metropolitan centre when it reported that there might not be readily available jobs for all the newcomers.

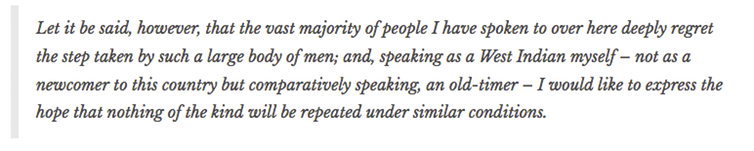

In the week of the ship’s arrival the Jamaican journalist, W A S Hardy reported “on the latest arrivals of West Indians who have come to try their luck in Britain”. His account was framed by details of a House of Commons session a few days earlier which agreed that the Welfare Department had done a “very good job” of accommodating the arrivals. Hardy, who had lived in Britain since the 1930s, added that while he was satisfied all was being done for the Windrush passengers, he had heard widespread regret about their arrival within Britain.

In the week of the ship’s arrival the Jamaican journalist, W A S Hardy reported “on the latest arrivals of West Indians who have come to try their luck in Britain”. His account was framed by details of a House of Commons session a few days earlier which agreed that the Welfare Department had done a “very good job” of accommodating the arrivals. Hardy, who had lived in Britain since the 1930s, added that while he was satisfied all was being done for the Windrush passengers, he had heard widespread regret about their arrival within Britain.

The overall mood of the new arrivals, he said, is “one of disappointment”.

The overall mood of the new arrivals, he said, is “one of disappointment”.

On another broadcast, the Jamaican poet John Figueroa, a key personality on the “Caribbean Voices” programme, witnessed the hospitality received by the Windrush arrivals, around 200 of whom were without exact plans and had neither friends nor relatives in Britain. He referred to their temporary accommodation at the Clapham Deep Shelter, their welcome by Colonial Welfare, and the warm reception they received from local churches and the mayor of Lambeth. But he added, more soberly, that their arrival was a great burden on the government.

By August 1948, and against the backdrop of the Windrush story, Figueroa was telling West Indian listeners of an “unpleasant and unfortunate” colour bar emerging around housing which prevented West Indians from finding suitable accommodation.

By August 1948, and against the backdrop of the Windrush story, Figueroa was telling West Indian listeners of an “unpleasant and unfortunate” colour bar emerging around housing which prevented West Indians from finding suitable accommodation.

Radio stars

But elsewhere, BBC programmes embraced the Windrush passengers more wholeheartedly to resource upbeat variety-style entertainment programmes. “West Indian Rendezvous” brought Mona Baptiste to the microphone on several occasions that summer. She was billed as one of the singing stars to recently arrive from Trinidad on the Windrush. Baptiste had modestly declared her occupation as “clerk” on the Windrush passenger list. But as the BBC broadcast noted, she was also a “well-known Blues singer” and went on to record hit songs and films in both London and Germany.

Other guests on the programme that summer included the calypso singer, Lord Beginner, who travelled on the Windrush with Lord Kitchener (of “London is the Place for Me” fame). Beginner delivered a calypso called “Hello to the Folks Back Home”, specially written for the BBC, which captured his journey with the characteristic exuberance of the calypsonian.

Windrush guest appearances had become so frequent by the end of July 1948 that the programme’s compere could declare they had nearly got through the whole passenger list.

Windrush guest appearances had become so frequent by the end of July 1948 that the programme’s compere could declare they had nearly got through the whole passenger list.

Prospective Caribbean migrants in 1948 could be forgiven for being confused by the mixed messages that emerged across such broadcasts. It’s not surprising that, in spite of the cautionary media narratives, so many threw caution to the wind and followed on other boats throughout the 1940s and 50s. Nor is it surprising to discover that Britain’s contemporary culture of “hostility” towards immigrants has a much longer history, as old as the Windrush itself.

Prospective Caribbean migrants in 1948 could be forgiven for being confused by the mixed messages that emerged across such broadcasts. It’s not surprising that, in spite of the cautionary media narratives, so many threw caution to the wind and followed on other boats throughout the 1940s and 50s. Nor is it surprising to discover that Britain’s contemporary culture of “hostility” towards immigrants has a much longer history, as old as the Windrush itself.