Get your credit card and check books ready

for this year’s King Holiday.

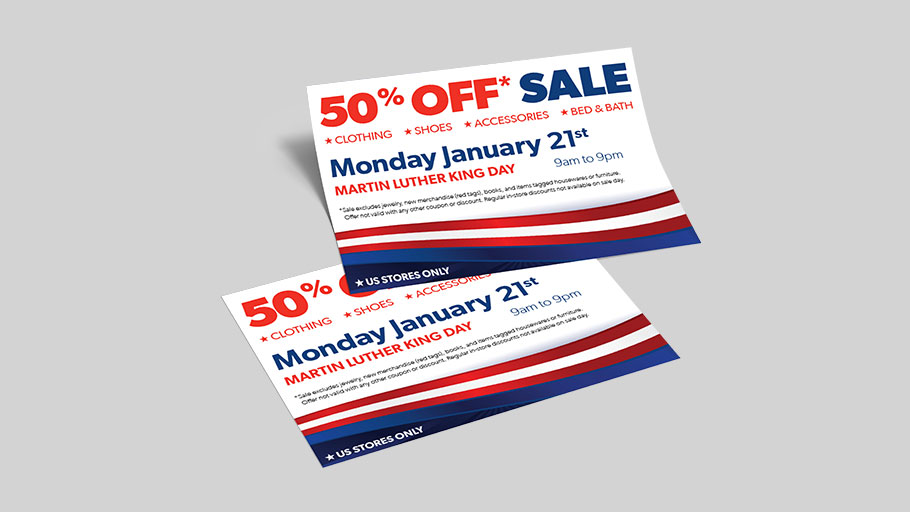

Here’s what The Gap Clothing retailer blazoned in an ad, “Over 500 styles MLK Event Huge Savings! Up to 50% off on items.” Macy’s quickly joined in and announced its MLK Day sale noting

“20 percent off sitewide with free shipping on qualifying orders. Further details are expected to be announced over the weekend.” Bloomingdales not to be left out announced a number of deals on home goods and sale items over the King Day weekend and throughout January. The Pottery Barn, Saks Fifth Avenue, Phonevite, and dozens of others are hawking every imaginable clothing item and product during King week.

The King holiday by the fifth decade after his assassination has become big, and a very profitable business, for retailers. There are the predictable grumbles that having sales and commercializing the King Holiday is virtually sacrilege and mocks everything that he stood for. Turning King into big business certainly does that. But it wasn’t hard to predict this would eventually happen.

Every major American holiday from Christmas on down has been transformed into a day not of religious observance (Christmas) or historical reverence (Presidents or Memorial Days) but a chance to make a buck. The bucks that are made are often the chance for big and small businesses to pad their profit margin with stepped up merchandise sales. For others, it can mean the difference between whether they stay afloat or close their doors. Despite the protests that commercializing holidays defames the significance of them, consumers have happily given their assent to the commercial hype by packing the stores on these days. So, the buy spirit is a two-way street, retailers promote, and consumers are conditioned through years of ad pitches and price enticements to shop and purchase on those days.

The King Holiday’s trajectory to becoming a commercially hyped holiday has been tortured. In the early years, it was widely shunned by a wide swatch of the public. Or, seen by many as a “black holiday.”

Major businesses, at least, in the beginning largely heeded the admonition of the King family and civil rights activists to keep their commercial hands off the holiday. It was to be celebrated as they repeatedly shouted as a day of remembrance of King’s dedication and commitment to civil rights and social change in America and globally. This was the noble, high road motive. The crasser reason was that most businesses simply did not see the day as important or popular enough to nudge large numbers of buyers into department stores. Who would think of giving a King Day gift or card?

The appeal by the King Center to make the day a day of service, oddly, did not seem to conflict with the retailer’s pitch to make it a day of profit for them. At no point, did the King Center expressly chide businesses for pumping the King Holiday as a day to buy. The silence, while not exactly condoning the increasing commercial bent of the day, gave implicit consent that the notion of performing a service act in the name of King and making a dollar off King were not inherently incompatible.

King would be repelled by the morph of his name into a dollars and cents proposition. There are many quotes sprinkled throughout his speeches and writings where he repeatedly condemned the unbridled quest for profit and materialism. In his 1967 speech denouncing the Vietnam War called the blind pursuit of wealth the corroded symptom of a “thing oriented” society. He went further and demanded that the nation undergo a “radical revolution of values.”

It isn’t just his words that give a tip as to how King regarded the unabashed pursuit of profit in his name. There was his personal life. He was an austere man and that extended to his household. He lived in a modest, rented home. It was dubbed “spartan-like simplicity.” He drove a 1960 Ford with more than 70,000 miles on the odometer. There were no second cars, maids, or helpers. The burden for caring for the children fell almost exclusively on Coretta’s shoulders. He donated his speaking fees, honorariums, and royalties from book sales to SCLC.

Then there was the Nobel Prize. It carried with it a purse of $54,000. Coretta wanted some of the money used for an education fund and other family necessities. King said no. He was emphatic that the prize money be used for civil rights activities and not for his and his family’s personal benefit. While King was not a pauper, by no standard could he be considered anywhere near wealthy at the time of his murder.

So, bargain sales, discounted items, and advertisements imploring shoppers to buy, buy, buy in his name are hardly the values revolution that King had in mind.

King almost certainly would not have been surprised that his name had become a commodity. He understood the fetish that a nation that put profit before people could operate in no other way than to turn anything of value into a sellable item. His murder, the holiday, and subsequent enshrinement as a towering historical figure, virtually guaranteed that one day he too would be just that; for many, namely a saleable item.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. He is the author of Fifty Years Later: Why the Murder of Dr. King Still Hurts (Middle Passage Press) He is a weekly co-host of the Al Sharpton Show on Radio One. He is the host of the weekly Hutchinson Report on KPFK 90.7 FM Los Angeles and the Pacifica Network.