Ras Baraka gave the Rev. Jesse Louis Jackson the key to the city on Saturday. He talked about why this had to be: all the struggles for social justice during a half-century. But knowing how hard it is to lead Black people, Baraka joked,“He gets it just for that.”

Jackson returned the joke, remembering how Baraka was a hell-raising undergraduate student at Howard University when Jackson lived in D.C. as a Shadow Senator in the early 1990s.

There were a lot of sharing moments like that at the Metropolitan Baptist Church fundraising dinner. During events like these in Newark, where seemingly everyone over 60 has a Civil Rights or Black Power story, time ceases to be linear, and instead seems to travel in connected circles.

This is important to say because, one day soon, Jackson will be silenced by a debilitating side-effect of his eldership. His Parkinson’s diagnosis hit some parts of Black America hard two years ago, and now hushed words swirled around and outside Saturday’s event, claiming that Rev is fading swiftly and his spoken flowers need to be delivered now. He seemed okay, cooking up his usual blend of African-American history, facts-’n’-stats and down-home-folkisms, leading chants—the whole soon-to-be-only-a-YouTube-memory schtick.

But yesteryear, the emperor had a much larger voice and wore serious, powerful vines. Jackson was recalled walking the streets of Newark in 1970, helping Amiri Baraka to get the fashioned-challenged Ken Gibson elected as the city’s first Black mayor. Gibson had on high-water pants, and his hair was cut too low, recalled Jackson, who was styling Black Power back then.

But yesteryear, the emperor had a much larger voice and wore serious, powerful vines. Jackson was recalled walking the streets of Newark in 1970, helping Amiri Baraka to get the fashioned-challenged Ken Gibson elected as the city’s first Black mayor. Gibson had on high-water pants, and his hair was cut too low, recalled Jackson, who was styling Black Power back then.

The elder Baraka, said Jackson, had “courage,” because “people in Newark were scared of [Anthony] Imperiale,” the Donald Trump of his day. On Gibson’s victorious Election Night, the masses poured out of the housing projects into the streets “as if Newark belonged to us.”

Now, the fading uncle, receiving the key, is publicly proud of the nephew who gave it, one who is and isn’t of his direct lineage. Mayor Baraka contains a lot of memory and genealogy within him, because he must. He is permanently surrounded, on both land and in the very air he occupies, by his father’s history, a multilayered one that has Jackson and other soon-to-be-Ancestors as co-stars.

Jackie Jackson kept the gratitude circling with the memories. She claimed that their life of public struggle, their 56 years of protest and pain, was no sacrifice, but a positive reaping of help that easily matched the one they had sown. She talked about how she thought she was doing Jesse Jr. a favor by writing to him in prison every day to make him strong, but the act was really making her stronger.

Jackie Jackson kept the gratitude circling with the memories. She claimed that their life of public struggle, their 56 years of protest and pain, was no sacrifice, but a positive reaping of help that easily matched the one they had sown. She talked about how she thought she was doing Jesse Jr. a favor by writing to him in prison every day to make him strong, but the act was really making her stronger.

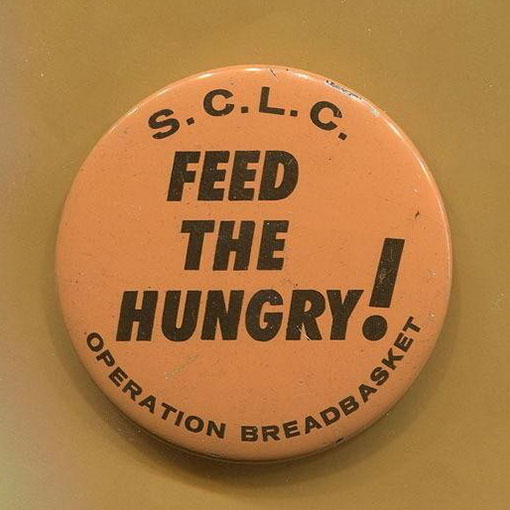

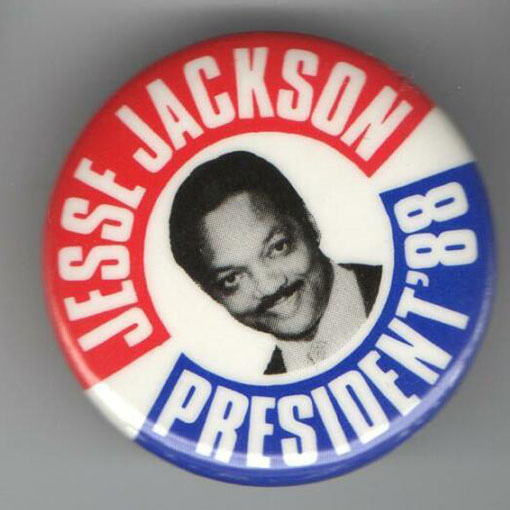

Strength and faith are the keys to Jackson’s city. With all of his faults, Jackson constantly raised self-esteem, even those of little children. Repeatedly, the audience pulled themselves back into 1988, when Jackson was running to push African-Americans further, into their own imaginations, past even what could not be seen at that Reagan-apartheid moment.

Ironically, it’s sometimes hard to see history’s bottom-rung ladder as 20-20 approaches. Next to this writer, a man had to explain to his young son who Jackson was: “He ran for President,” the father told a teenager who probably only remembered the president being Barack Obama, who only knew that entitled victory. The former president is Jackson’s legacy whether both men like it or not.

“We’re not the bottom; we’re the foundation,” said the man of yesterwhen’s honor. But that foundation, that soil, is filled with recent bodies. Jackson, 77, mentioned that most of his friends are either dead, crippled, maimed or have dementia. (“They be singing Easter songs at Christmastime,” he declared to exploding laughter.) Jackson will soon run and gab no more. But the most permanent statues remain forever beautiful in their stillness and muteness, and the stimulation they hopefully create.

“We’re not the bottom; we’re the foundation,” said the man of yesterwhen’s honor. But that foundation, that soil, is filled with recent bodies. Jackson, 77, mentioned that most of his friends are either dead, crippled, maimed or have dementia. (“They be singing Easter songs at Christmastime,” he declared to exploding laughter.) Jackson will soon run and gab no more. But the most permanent statues remain forever beautiful in their stillness and muteness, and the stimulation they hopefully create.

Todd Steven Burroughs is the author of “Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates” and “Warrior Princess: A People’s History of Ida B. Wells.”