It was a festive occasion at City College on Nov. 20, 1998 when the great writer George Lamming was saluted with the Langston Hughes Medallion, a tribute to his remarkable literary career. Only a few of the younger students in attendance were fully aware of this eminence grise whose wide-ranging speech centered on the history of anti-colonialism, but they were riveted by his lyrical voice that retained a certain West Indian twang.

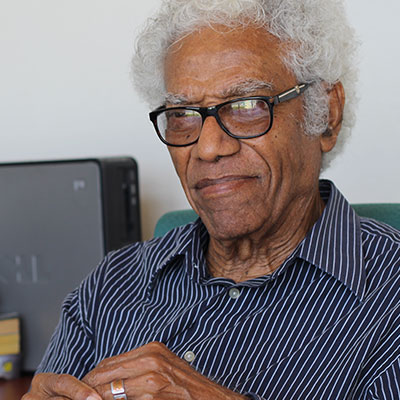

George Lamming

That melodious voice was silenced on June 4, but his words are forever with us, most rewardingly in his novel, In the Castle of My Skin, published in 1953. He was 94. According to another famed scribe, C.L.R. James, a close friend and associate of Lamming, his colleague’s “novels are permeated by the sense of the role of different classes in West Indian society. His work is an expression of Barbados,” James cited in Spheres of Existence. And that was perfectly logical because Lamming was born on the island nation in 1927 and never lost a probing and enlightened intimacy with it, despite spending part of his early manhood in England.

His first novel was imbued with a broad mix of genres—it was part roman clef, an extended epigraph, an amalgam of experiences that taken together captured the essence of a people determined to obtain their liberation from oppression. Again, James summarized a portion of Lamming’s style, intensity, and his singular quality by quoting the author himself. “Free is how you is from the start, an’ when it look different you got to move, an’ when you movin’ say that it is a natural freedom that makes you move.”

Lamming indeed moved with a natural unbridled freedom and it resonated from each of his books, particularly, The Emigrants that followed on the heels of his first novel; Of Age and Innocence (1958); and Season of Adventure (1960); The Pleasures of Exile (1960); Water with Berries (1971); and Natives of my Person (1972). These books were interspersed with numerous essays and lectures, many of which engrossed students at Duke, Brown, Cornell, and other prominent academies. In one interview he stated that “I became a West Indian in England,” and some of that coldness, both from people and the weather, flows without apology from The Emigrants and Season of Adventure.

When the news of Lamming’s passing reached the students and faculty at the University of the West Indies, said Professor Sir Hilary Beckles, the university’s Vice Chancellor, “it punctured the peace of mind of the academic community…where he was Professor in Residence at the Cave Hill Campus. It was there in his office at the George Lamming Pedagogical Centre, that we last met and occupied ourselves for a few hours with one of Miles Davis’ last statements: that time is never enough to exhaust the ever giving, producing, creative imagination of the dedicated intellect.

“George was a phenomenal philosopher,” Beckles continued, “who erupted in the literary world early in life with the publication in 1953 of a classic novel of anti-colonial consciousness—In the Castle of my Skin—written during his 23rd year of life. From his Bridgetown Village, he traversed the intellectual universe and provided it with pedagogy of liberation that underpinned Pan-Africanism, socialism, and a 20th century humanism that included feminism, dialectical materialism, and the Caribbean Cultural Revolution. His embrace of Cuban socialism became a template for his support of Maurice Bishop and Walter Rodney in their quests to detach the neo-colonial region from the scaffold of rejected imperialism.”

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, echoed Sir Beckles’s sentiments, noting that “Wherever George Lamming went, he epitomized that voice and spirit that screamed Barbados and the Caribbean.”

And that scream, that undeniable rebel yell that characterized his activism will be unceasing so long as his books are read, his poems recited, his lectures quoted and passed on to future generations.

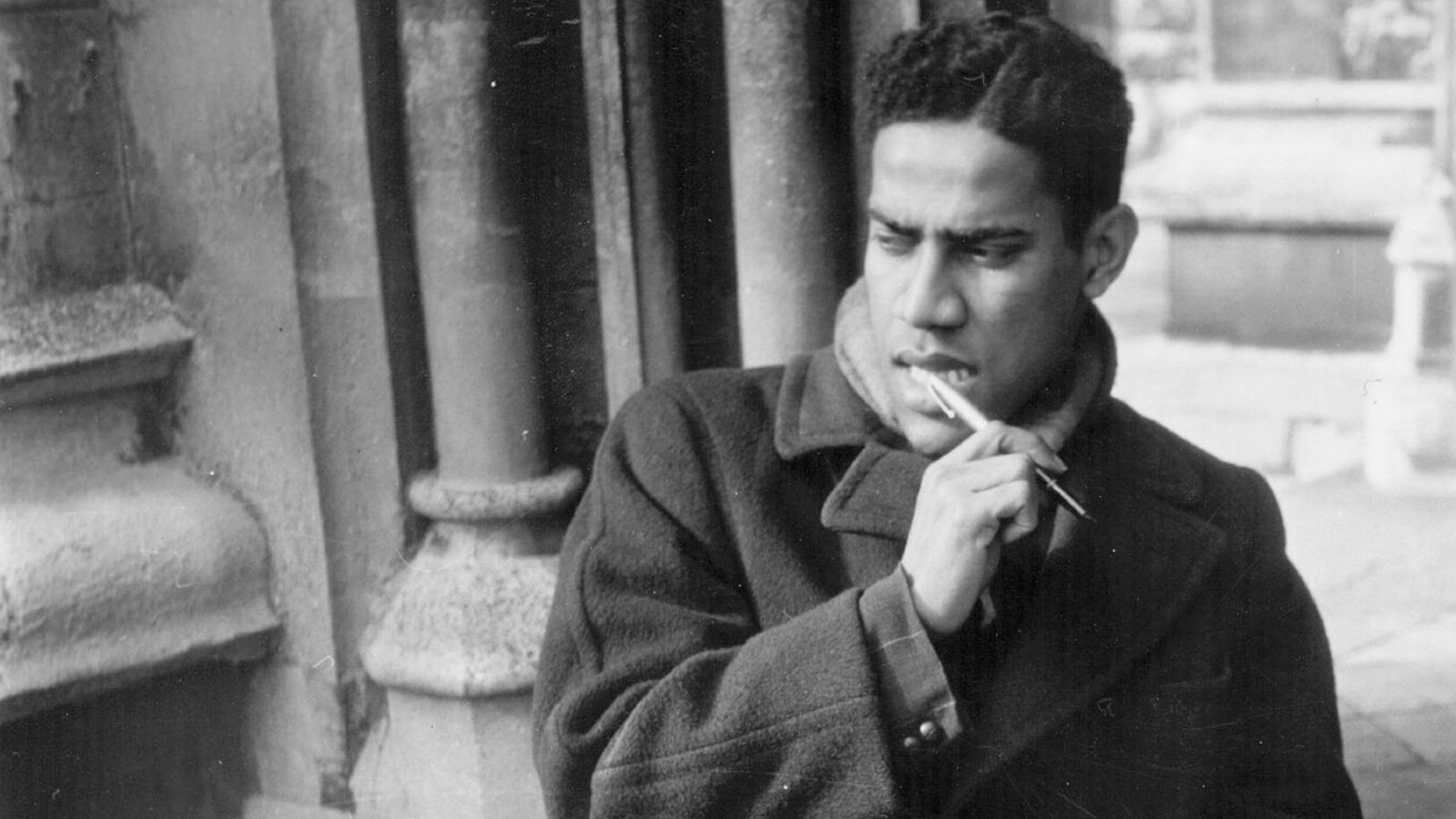

Featured image: George Lamming in London in the early 1950s. Photograph: George (Douglas, Getty Images).