As the leader of the police union has raged, incited and poured rhetorical gasoline on a tense city, every other significant labor union has gone mute. Not one of them seems able, or willing, to speak up and blunt the din unleashed by the PBA at the mayor, protesters and just about anyone who doesn’t share Pat Lynch’s world-view.

Prisons employ and exploit the ideal worker. Prisoners do not receive benefits or pensions. They are not paid overtime. They are forbidden to organize and strike.

There were two big takeaways from President Obama’s Cuban opening. The first is obvious. After 55 years of U.S.-backed invasions, covert efforts to sabotage and overthrow Fidel Castro…

This has not been a good year for black males and law enforcement officers but it is also a year that has dramatized the troubled nature of national security in America.

Black sororities must remember their real brand is Black womanhood; intelligent, strong and culturally conscious, and not Greek letters

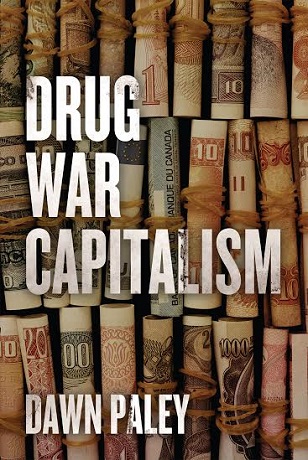

If there really was a war on drugs, it wouldn’t make for very good media fodder: bullet-riddled packets of cocaine (or cigarettes, for that matter) don’t bleed, and following the newspaper industry rhyme…

The word “Ferguson” has become synonymous with racism and police brutality in the U.S. today, in the same way that the name “Rodney King” did in 1992. And yet there remains a persistent and reactionary response from some white Americans who vehemently view themselves as the victims and black Americans as “violent thugs” who deserve the treatment they receive from police and the criminal justice system. The doublethink of domination and victimhood is central to the pathology of white supremacy in the U.S. It is used to dupe and confuse us into believing that there is nuance in brutality and justice in murder.

This Friday, December 12, 2014, the Jamaica National Movement and the Jamaica Progressive League will hold a panel discussion on the legacy of the former Jamaican Prime Minister, Michael Manley.

With each successive march on the nation’s capital we seem to move further away from the substance and critical organizing that marked the 1963 march.

Jess Zimmerman: Hi, Rebecca! First of all, thanks for talking this out with me, and I hope I don’t come off like a jackass. The internet exerts a powerful jackass ray, and lord knows so does talking about race, and we are essentially crossing the streams here. Anyway, after the Ferguson grand jury verdict came down, I tried to spend the night just RTing black folks on Twitter.

A strange coalition has formed around the police officer-worn body camera.