By Peniel E. Joseph, New Republic

Even in the splintered and often fractious world of social justice movements, Black Lives Matter doesn’t fit easily into existing categories. Few grassroots uprisings have done as much, in such a short period of time, to focus attention on long-neglected issues of racial justice, gender, and economic inequality. Yet so far, BLM has not followed up on its initial victories by building the kind of lasting, hierarchical organizations that grew out of the civil rights movement; nor has it dedicated itself to a single, easily identifiable goal, like enacting the Voting Rights Act. How are we to make sense of organizers who themselves remain so loosely organized? And if Black Lives Matter isn’t devoting itself primarily to bringing about substantive legal and legislative change, then how can it hope to transform its resistance into lasting and meaningful gains in human rights?

Such questions are understandable, given the course that BLM activists are charting for their organization. But comparing the group to the civil rights movement betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of both its importance and its broader agenda. BLM was certainly inspired, in no small measure, by the nonviolent civil disobedience that was so effective during the civil rights era. But its unique contribution comes from the way it has married those grassroots tactics to the radical structural critique of institutional racism and economic injustice developed by the Black Power movement. In so doing, it has issued a clarion call to an entire generation of social justice activists, placing the fledgling movement on the cutting edge of civil rights activism for the twenty-first century.

Comparing BLM to the Black Power movement, of course, is not without pitfalls. Many critics have been quick to dismiss BLM for trafficking in the angry polemics exemplified by groups like the Black Panthers. Indeed, Black Power is often viewed as the evil twin of the civil rights movement, one that undermined the heroism of more mainstream leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. In the popular imagination, Black Power exists as a kind of fever dream, populated by gun-toting Black Panthers, student militants who took over university campuses, Muhammad Ali’s refusal to fight in the Vietnam War, and Malcolm X’s insistence that black Americans would be justified in resorting to violence to defend themselves from the violence of entrenched racism.

The reality is richer—and far more resonant to our current moment. The Black Power movement’s greatest achievement was turning racial consciousness into a weapon that could be used to promote institutional change. Transforming “Negroes” into proud black people wasn’t a rhetorical flourish—it was an essential and strategic move that helped bring about a corresponding transformation across a broad spectrum of racial identity.

Black Power inspired sweeping changes in American literature, art, and poetry; created a new wave of black scholarship in higher education; and helped elect two generations of black officials at every level of government. Without the consciousness-raising of the Black Power movement, there would likely be no King holiday or Black History Month, no movements to end mass incarceration or apartheid, no free breakfasts in public schools (an outgrowth of hot-meal programs launched by the Black Panthers), no black studies programs at Harvard and other major universities, no Do the Right Thing or Lemonade, no Barack Obama.

Like BLM, which was born in the wake of widespread incidents of police brutality, Black Power came of age in the violent racial landscape confronted by civil rights activists. If Martin Luther King presented himself as a shield capable of defending the black community from the evils of racial segregation, Malcolm X entered the world stage as a sword capable of defeating a Jim Crow system that excluded and brutalized black Americans. “Message to the Grassroots,” Malcolm’s historic speech in Detroit in November 1963, offered a blueprint for a black revolution, one sophisticated enough to recognize white supremacy as a national issue, rather than a regional concern, and bold enough to deploy radical strategies—including armed self-defense and political self-determination—to defeat it.

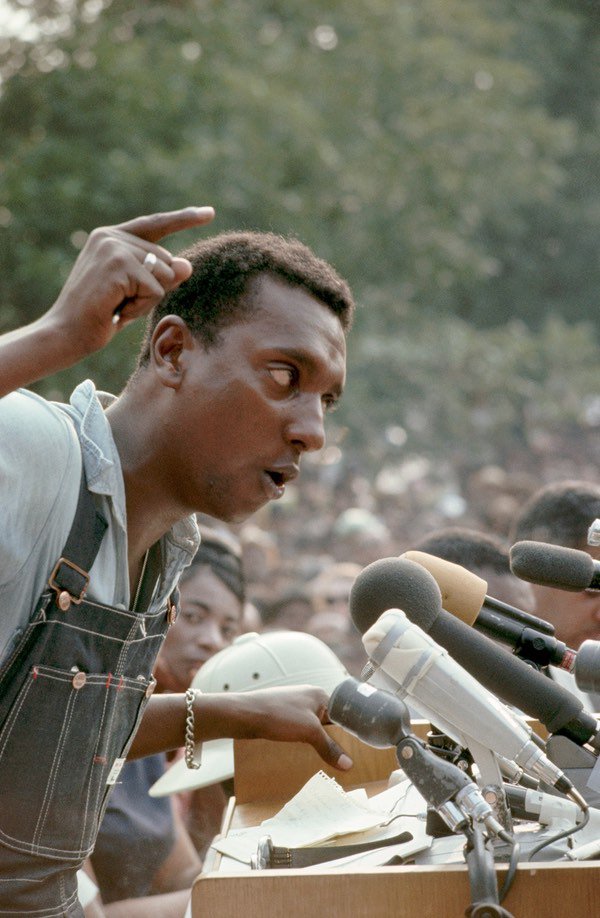

The movement gained its name three years later when Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture), a Trinidad-born student activist who became a leader among the Freedom Riders and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, gave a speech in Greenwood, Mississippi, calling for “Black Power.” To Carmichael, Black Power was a call for radical self-determination: social, political, economic, and cultural. Black people, he insisted, had the right to define the framework of racial oppression—and the tools to combat it—for themselves.

Stokely Carmichael’s 1966 “Black Power” speech in Greenwood, Mississippi, called for black self-determination and self-defense. Flip Schulke/Corbis/Getty Images

“A new society must be born,” Carmichael insisted in one of his most important and powerful speeches, before 10,000 people at the University of California in Berkeley. “Racism must die,” he said, and “economic exploitation of nonwhites must end.” He then posed a fundamental question that BLM activists implicitly continue to ask: “How can white society move to see black people as human beings?”

The Black Panther Party answered this question with a vengeance. Inspired by Malcolm X, anti-colonial movements in Africa and Latin America, and an eclectic reading of Marxist-Leninism and the literature of Third World revolution, the Panthers (whose leadership at times veered toward authoritarianism and violence) deliberately cut a combative posture to strike fear in white Americans. But like BLM, the group quickly expanded its initial focus on police brutality to embrace a ten-point program that called for the radical transformation of American democracy. Within a year of their founding, the Panthers ended their armed surveillance of white police officers, and created local chapters in poor black neighborhoods that provided free breakfasts, health care, legal and housing aid, drug rehab, and transportation to visit relatives in prison. Equally important, the group’s revolutionary politics evolved into a full-blown anti-imperialist framework that connected racism and economic injustice at home with America’s wars in Vietnam and beyond.

Like the Panthers and others in the Black Power movement, BLM rose to prominence in a landscape of police violence and entrenched racism. The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was created in 2013 by Opal Tometi, Patrice Cullors, and Alecia Garza, three queer, black activists who were outraged at the acquittal of the “neighborhood watch” volunteer who shot and killed 17-year-old black Trayvon Martin. BLM evolved into a full-fledged movement during the urban rebellions in Ferguson in 2014 and Baltimore in 2015. Those political uprisings, like the larger conflagrations that spread throughout America during the long, hot summers from 1963 to 1969, represent a direct confrontation of institutional racism and economic injustice.

But BLM has moved beyond many of the blind spots and shortcomings of its predecessors, embracing the full complexity of black identity and forging a movement that is far more inclusive and democratic than either the Panthers or civil rights activists ever envisioned. Many of its most active leaders are queer women and feminists. Its decentralized structure fosters participation and power sharing. It makes direct links between the struggles of black Americans and the marginalization and oppression of women, those in LGBTQ communities, and other people of color. It has made full use of the power and potential of social media, but it has also organized local chapters and articulated a broader political agenda.

Last summer, following critiques that they had failed to put forth specific demands, BLM activists and affiliated organizations published “The Movement for Black Lives,” a detailed and ambitious agenda. Divided into six parts, it includes a host of interconnected demands: a shift of public resources away from policing and prisons and into jobs and health care, a progressive overhaul of the tax code to “ensure a radical and sustainable redistribution of wealth,” expanded rights to clean air and fair housing and union organizing, and greater community control over police and schools. More detailed than the ten-point program issued by the Black Panthers, the BLM policy agenda offers a remarkably pragmatic yet potentially revolutionary blueprint—one that it aims to implement through the concerted use of both protest and politics.

Unlike the activists of the civil rights era, those in BLM do not feel forced to make an either/or choice about which model of black liberation struggle they follow. Instead, BLM has merged the nonviolent civil disobedience of the civil rights movement with the radical structural critique of white supremacy and capitalist inequality articulated by Black Power activists. Indeed, the decentralized organizational philosophy of BLM most closely mirrors that of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Founded in the aftermath of the sit-in movement that swept the South in 1960, SNCC became the most important grassroots social justice organization of the era. It served as a convergence point for several overlapping, at times contradictory, political tendencies. Christian pacifists, black nationalists, liberal integrationists, black and white feminists, and peace activists were all, at various points, a part of the group, which successfully straddled the competing models of black identity advocated by the civil rights and Black Power movements.

Like SNCC, BLM embraces what we now call the intersectional nature of black identity. By placing the lives of trans and queer black women, young people, and the poor at the center of its policy agenda, the group has enlarged our collective vision of what constitutes membership in the black community. In doing so, it has expanded the terrain of what it means to be human in a society that has, since its inception as a democratic republic founded in racial slavery, insisted that black lives were disposable. Whatever future success it achieves on the policy front, BLM recognizes that what Malcolm X called a struggle for “black dignity” has always traveled a path toward universal human rights. Freedom for black Americans, the group reminds us, ultimately means a better nation for all. Until the most marginalized among us—the trans teenagers traumatized by dehumanizing legislation, the Latina and queer youth with no access to HIV treatment, the single black women struggling to raise their children while holding down three jobs—are recognized as part of our collective American family, we all remain imprisoned.

Peniel E. Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and professor of history and founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas, Austin. He is author of Waiting ’Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America and Stokely: A Life.