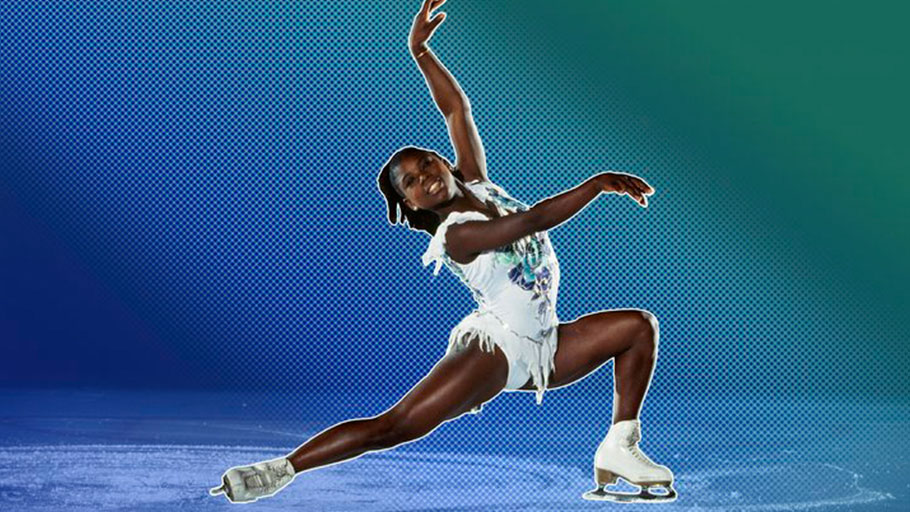

Illustration: Damon Dahlen/HuffPost, Photos: Getty Images

Surya Bonaly was art to watch. My mama, home on a rare half-day from work, was flipping through our local TV channels and, seeing a new black ice skater, hurried to record her on a VHS tape she reserved exclusively for classic movies and occasional Oprah Winfrey shows. After I got in from school, she slid it into the VCR. “Watch this little black girl,” she said as she smiled down at me. “She’s amazing.”

Surya glided onto the ice, all poise and confidence, her mahogany skin shimmering against the manmade glitters and sparkles of her sequined costume, and posed for her music to start. It was something classical — ice skaters always used classical music — but she moved around the rink less like a ballerina on blades and more like a bedazzled superhero.

She was sturdy and compact ― like me ― and the standard toe loops and salchows incorporated into her routine took on a completely different look when they were performed by Surya’s body. They were more powerful, more athletic, more demanding of space. Then, like a ninja warrior acrobat, she lifted herself off the ice, tossed her frame against the air and tumbled into a perfect aerial backflip to land on a single leg. She remains the only professional skater of any gender to successfully achieve the feat. Surya was Black Girl Magic before it had a name and a hashtag.

There’s a difference between having representation and having representatives.

This week, the Winter Olympics will commence in Pyeongchang, South Korea, and magnificent athletes are adding their names and credentials to the black history we’re already celebrating this month: Maame Biney, the first black woman to qualify for a U.S. Olympic speedskating team; Seun Adigun, Ngozi Onwumere and Akuoma Omeoga, the first Nigerian bobsled team in the Winter Olympics; Erin Jackson, the first black woman to join the U.S. Olympic long-track speedskating team and, at that, just four months after she took up the sport.

Some other young girl will watch them compete. They will become someone else’s Surya Bonaly.

We talk often about why representation is important, and it is. But there’s a difference between having representation and having representatives. Representation throws a spotlight on what is already great about blackness but is not often enough seen, much like the majesty that will unfold at the Olympic Games. Representation gives us films like ”Girls Trip” that highlight our humor and ”Black Panther” that highlight our power and creativity. Representation lets us see regular, degular girls like Cardi B rise to mainstream success. Representation brings blackness from the outskirts of culture into the mainstream for everyone to appreciate and for black people especially to rejoice in.

Representatives, on the other hand, are a conciliatory gesture to create the illusion of inclusion and appreciation. J. Crew puts black girls in bad hair and makeup and expects us to be thankful to just be on screen. ABC throws one black contestant in for a season of ”The Bachelor,” but she’s likely leave without a rose within the first two weeks, quickly forgotten. H&M puts a black boy in its new “Coolest Monkey in the Jungle” hoodie, seemingly without thinking twice about the implied racism.

Representatives are manufactured in the boardrooms of companies and institutions with little incentive to understand, much less celebrate, black people, but with the full intention to poach and commoditize black culture and its $1.5 trillion in consumer spending power. They toss a black person into their marketing mix to dodge the wrath of Black Twitter and the ire of the black think pieces because — look! — diversity. And black people take these potentially lucrative opportunities because they work hard and deserve to be seen (or at least paid). But that does not mean it doesn’t hurt to be tokenized. And it hurts in more ways than one.

Often, this act of finding race representatives excludes more people of color than it makes opportunities for them. Model Chanel Iman spoke out about designers who’ve dismissed her from fashion show opportunities, telling her they’ve “already found a black girl and don’t need another one.” Actress Zoe Kravitz has been open about turning down stereotypical roles of a girlfriend or someone in the projects.

It’s great to have an international platform to applaud the accomplishments and giftedness of black men and women.

True representation is intentional, purposed, meaningful. It seeks to implement lasting change in the way black people are portrayed, in the way our stories are told. Seeing a face that looks like mine, doing amazing things on screen, in books or in sports, reminds everyone ― not just black people ― that we are more than our struggles. We’re also our successes.

Representation lifts up the complexities and nuances of black folks’ experiences, not as a tidy acknowledgment during Black History Month but in real efforts to understand and circumvent the external systems that have created the dynamics we navigate, reconcile and overcome all year round.

It’s great to have a dedicated month to commemorate peak blackness. It’s even greater to have an international platform to applaud the hard-earned accomplishments and giftedness of black men and women who will set new personal bests, demolish existing records, do the undoable in big, audacious ways. It’s not an anomaly. Our people are in communities doing the amazing every day: teachers, activists, coaches, parents, mentors, counselors, storytellers, political leaders. They do the work. They deserve to be seen. They are our representatives. They are the administrators and protectors of black love and joy, and the spokespersons for black glory.

Spoiler alert: I didn’t grow up to be an ice skater. Even though my mama had been so excited to show me the saved footage of Surya Bonaly in action, I didn’t even bother to ask her for ice skating lessons (which would have almost certainly been clapped down with some variation of “you got ice skating lesson money?!”). I quietly admired Bonaly for her craft, and I started developing my own as a writer. I didn’t think about the challenges she’d experienced to get there, maybe even on her way to the ice just moments before she took the ice. I knew that her being there mattered. Because she could do the thing she chose to be great at, I could do the same. It wasn’t an exclusive permission, but it was an inspiration.

As I prepare to root for everybody black at this year’s Olympic Games, I’m reminded of all of the inspiration and motivation I got from seeing one black girl doing a backflip on national television. Imagine the world of creators, entrepreneurs, athletes and artists we could create if every time a little black kid turned on the TV or the radio or opened a magazine, they saw someone who looked like them, doing something amazing. Or simply just existing, in all their glory.