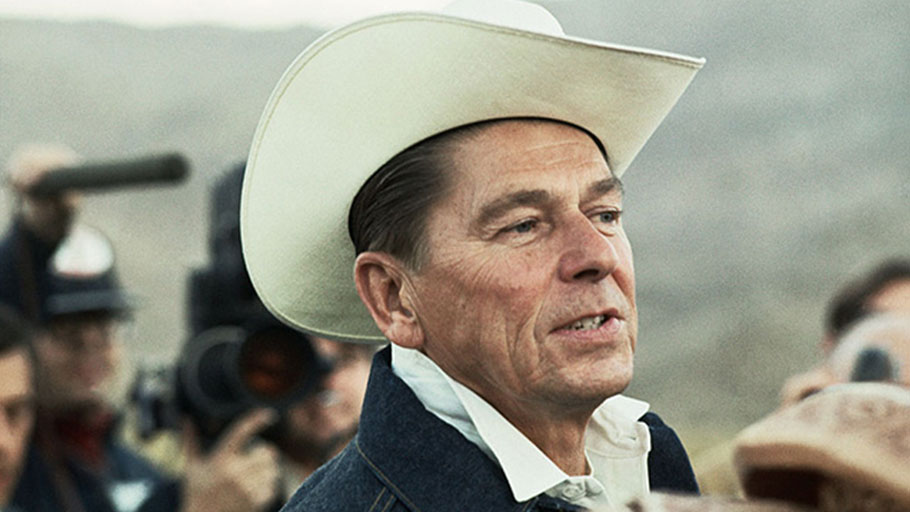

Then-Governor Ronald Regan speaks on December 5, 1968. He later went on to become president of the United States, ushering in a severe era of neoliberal economic policy that has continued to this day. (Photo: Bettmann, Getty Images)

By T.J. Coles, Clairview Books —

In the early 1970s, the Nixon administration pushed to eliminate what neoliberal advocates call “needless barriers to competition.” This was particularly true of the financial sector, where restrictions on local bank branches, prices for deposits (so-called regulation Q) and compartmentalization (i.e., allowing the interconnection of commercial, savings and insurance) were lifted.

Experts Campbell and Bakir identify four “pre-neoliberal attacks,” which transformed the US economy into a neoliberal one:

- Bank holding companies were established as a way of circumventing the McFadden Act 1927, which restricted the geographical competition of banks. Until the 1970s, the majority of America’s 14,000 banks were single units.

- Regulation Q meant that banks had to find creative ways of using money market instruments to finance businesses. New York banks in particular transformed into highly liquid markets to attract corporate customers. Negotiable Certificates of Deposit were issued to undermine regulation Q. The Money Market Mutual Funds, introduced in 1971, streamlined the process. They expanded the liquid secondary business markets from $3bn in 1976 to $80bn in 1980, then to $230bn in 1982. Most of this was worthless cash.

- The credit contractions of 1966-70 describe a period in which European banks essentially laundered US money to allow them to avoid Q-restrictions. By 1975, Euromarket loans had exploded from $25bn in 1968 to $130bn.

- Bank holding companies were also used to undermine financial regulations, particularly the rules on compartmentalization. A 1973 Congressional report found that bank holding companies were “act[ing] as investment advisors to real estate investment trusts and mutual trusts” by leasing personal and real property, providing services (including bookkeeping and data processing) and “operating insurance agencies.”

Things were getting messy and more volatile.

The Carter-Reagan Years

In 1978, the Supreme Court ruled that banks could export state usury laws. This led to the elimination of usury rate ceilings in several states and benefited bubble markets: liquidity firms and issuers of credit cards, especially Citibank.

In 1980, President Carter signed the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act, which increased deposit insurance from $40,000 to $100,000. The Act empowered savings and loan companies (S&Ls) and led to the crisis of the 1980s. S&Ls specialize in mortgage and real estate lending. The Act also phased-out interest rate ceilings on deposit accounts.

“Under Ronald Reagan we had the best corporate tax rate in the industrialized world,” writes Donald Trump in his book, Great Again (2015, p. 155). Ronald Reagan also oversaw major deregulations of the financial sector. Economists Diamond and Dybvig write: “In the 1950s and 1960s the banking industry was a symbol of stability. By contrast, recent years have seen the greatest frequency of bank failures since the Great Depression.”

In 1979, the Fed doubled interest rates to reduce inflation. As a result, savings and loan (S&L) associations issued their customers fixed-interest loans at lower rates than the borrowing rate. This led to mass insolvency among S&L companies, which failed to attract capital. In 1981, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board decided to allow S&Ls to get away with lax accounting procedures. This led to major fraud. The Board was then decentralized to oversee banks and S&Ls at the regional level, which weakened its regulatory power. The Federal Deposit Insurance Cooperation noted that the Board was so influenced by financial lobbyists that it was essentially a “doormat[…] of financial regulation.”

The Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act 1982 reduced the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s oversight and introduced restrictions on minimum stock ownership. Deregulation also allowed S&Ls to adjust mortgage rates and expand lending practices. In a move that essentially provided S&Ls with taxpayer coverage, S&Ls switched from state to federal charters.

New accounts were opened to allow companies to compete with Money Market Mutual Funds, which are short-term bond holders. “Nearly every state … still had strict usury laws on their books, but banks were able to charge any interest they wanted nationwide,” writes Matthew Sherman of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Under Garn-St. Germain, S&Ls were allowed to act more like banks and less like specialized mortgage lenders.

Savings & Loan Crisis Continues

By 1983, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation held only $6.3bn in reserves to rescue institutions like S&Ls, yet S&Ls were already $25bn in debt. S&L portfolios shifted away from home mortgage loans to risky real estate ventures, like condominiums. By 1986, S&L home mortgage assets had shrunk from 78% to 56%.

A bubble was blown by S&Ls issuing credit cards, lending up to 20% of their assets, investing up to another 20% in real estate and writing limitless cheques in a process called negotiable order of withdrawal accounts. Congress then passed the Economic Recovery Tax Act 1981, which allowed S&Ls to sell mortgage loans and offset losses against tax for a decade. Wall Street bought a load of bad S&L loans, some up to 60% of their value, and bundled them as taxpayer-backed loans through guarantees by the banks Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae and Freddie Mac. By 1986, the bonds were bought by S&Ls for $150bn.

In three years (1982-85), S&L assets grew by 56%, signalling a crash. S&Ls started making riskier and riskier investments as deregulation allowed them to hold certificates of deposit (i.e., federally-insured savings) at high interest rates. In addition, individual bankers were responsible for a large number of frauds and scams. Between 1986 and 1995, nearly a third of America’s 3,234 savings and loan associations crumbled. By 1989, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation closed or resolved 296 organizations, when it was replaced by the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC). Up to 1995, the RTC closed or resolved 747 institutions. The taxpayer forked out $100bn.

The Clinton Years

The final nail in the regulatory coffin was the Bill Clinton administration (1993-2001). Clinton repealed laws and prevented government intervention in speculative markets, until they collapsed. These deregulations built upon the Nixon-Reagan era and ultimately contributed to the Crash of 2007, the Crisis of 2008 and the ongoing Recession.

Clinton’s government approved NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement; a lengthy legal text between the governments of America, Canada and Mexico. It was drafted in secret and in opposition to the labour unions, which didn’t even get to see a draft copy until it was too late. NAFTA is the very symbol of “free trade” and neoliberal globalization. It created a customs union between the three signatories and eliminated barriers to trade. This was good for consumers because prices went down. It was bad for American factory workers because US companies not only relocated to Mexico, where they enjoyed cheaper labour and lower health and safety standards, but could also threaten to offshore as a way of intimidating unions.

NAFTA was devastating for Mexican farmers who could not compete with huge imports of mechanized American products. NAFTA is in part why so many Mexicans are seeking work in the US. NAFTA is also bad for Canada’s environment. NAFTA provisions allowed signatories to be sued for interfering with corporate profits. Under Chapter 11, Canada became the world’s most sued nation by corporations (mostly American) which challenged various environmental laws introduced by the Canadian government as threats to their profits.

Donald Trump has been very critical of NAFTA, threatening to renegotiate to get a better deal for America — meaning its corporations — or else withdraw from the treaty. Yet NAFTA has its origins in the Reagan administration. A North American Accord was proposed in 1979 by the Republican Ronald Reagan shortly before his taking office as President. The Democrats in Congress voted against the Accord until 1992, when Bill Clinton was elected. Under Bush I in the 1980s and early 1990s, the US had already liberalized the Mexico peso in exchange for providing Mexico with loans. Mexico was in no position to argue.

A report by Cornell University notes that in the US, union membership had declined from over 50% in the 1950s to 12% by the 1990s, due in large measure to aggressive anti-union laws, policies, and practices. “US workers, trade unions and their allies … mounted a strong campaign of opposition to NAFTA.” This was due in part to Clinton’s refusal to include a strong Social Charter. The Citizens Trade Campaign (sic) and Alliance for Responsible Trade were formed by concerned citizens.

Despite their efforts, NAFTA was approved by Congress on a vote of 234 to 200. Unions were given almost no time to read the huge document. Despite this, they managed to write a critical report which was largely ignored by Congress.

Unhappily Ever NAFTA

According to a report by the US Economic Policy Institute, NAFTA cost American workers 700,000 jobs, many of which were moved to Mexico. California, Michigan and Texas were the hardest hit. Surviving sectors saw a decrease in wages and benefits, with bosses using the threat of off-shoring to Mexico as a way of driving down labour costs and unionization. NAFTA was a big contributor to Mexican migration to the US.

The EPI report goes on to note that “several million Mexican workers and families” were adversely affected in the agricultural and small business sectors by imports of cheaper US goods. “[T]he dramatic increase in undocumented workers flowing into the US labor market … put further downward pressure on US wages.” The report concludes that NAFTA was a “template” for a world trading order “in which the benefits would flow to capital and costs to labor.”

In 1994, Clinton signed the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act, which eliminated restrictions on interstate banking and branching. Mergers increased by 27% in an eight-year period. In 1996, the Supreme Court eliminated some of the limits on late fees for credit card payments (Smiley vs. Citibank). The Court overruled state regulations and late fees jumped from $5 to $40.

The biggest merger took place in 1998, when the Fed approved the Citicorp-Travelers merger, which allowed the liquidity firm Citicorp and the insurance giant Travelers to create the biggest financial institution to date. This put America well on the way to having an economy monopolized by a few financial institutions.

In 1999, Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act which repealed Glass-Steagall, the benchmark of financial regulation. The repeal of Glass-Steagall was supported by Fed chairman Alan Greenspan and Treasury secretaries, Robert Rubin (ex-Citigroup and later Goldman Sachs) and Lawrence Summers. The Act allowed the actions of banks, securities and insurance companies to merge for the first time since the 1930s.

In 2000, Clinton signed the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which prevented the Commodity Futures Trading Commission from regulating most of the financial transactions known as derivatives. Derivatives can become so complicated and cause so many financial institutions — asset firms, banks, insurers, mutuals, trusts — to suffer, that multibillionaire hedge fund CEO Warren Buffett famously describes them as “financial weapons of mass destruction.”

The head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Brooksley Born, warned about the risks of unregulated derivative markets. It has been alleged by various economists that Lawrence Summers personally intervened to prevent Born from acting on her concerns. The Act was passed by Congress without objection because it was sneaked through as an attachment to an 11,000-page spending bill. The derivatives market exploded from $106tr in 2001 to $531tr by 2008, when the market — triggered by rising oil prices and the housing collapse — finally imploded.

Dr. T.J. Coles is the author of several books, including The Great Brexit Swindle and President Trump, Inc. (both Clairview Books titles).