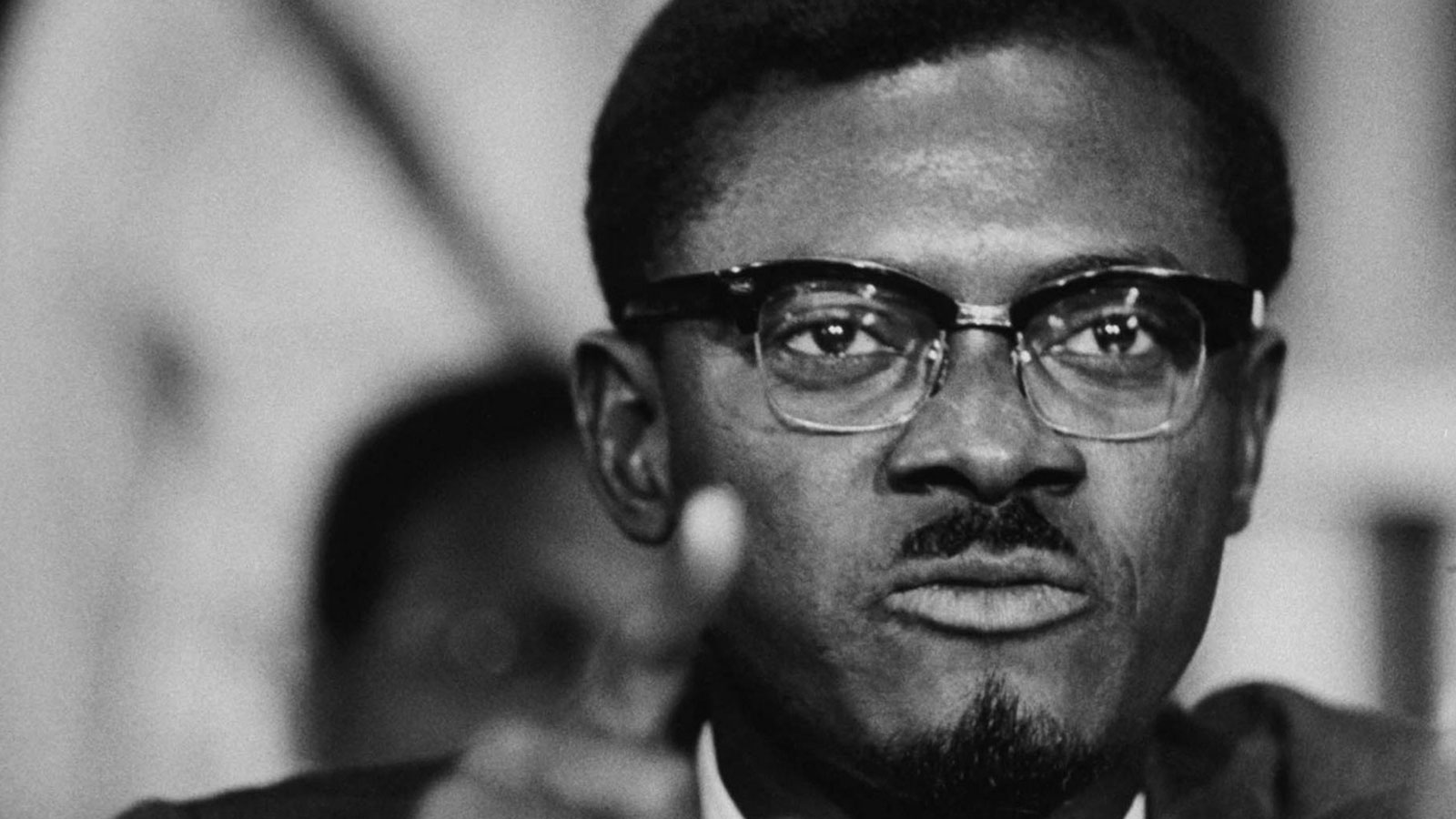

In our long, difficult, dangerous and demanding struggles to liberate ourselves as African peoples, to regain our freedom we had at birth and enjoyed for thousands of years before Europe, colonialism, imperialism, racism and the resultant rot and retardation of human relations, there are countless men and women whose lives and deaths offer libraries of lessons, models and mirrors of living and dying in rightful and righteous ways. And such a man and African is Nana Patrice Lumumba (July 2, 1925 – January 17, 1961). Leading the Democratic Republic of the Congo to independence June 30, 1960, and assassinated and martyred at 35, Nana Patrice, in his brief life, leaves an awesome and enduring legacy of work and struggle to regain African freedom and in the process, he offers vital lessons of how to live and die in dignity-affirming, life-enhancing and world-preserving ways.

Speaking of this honored Congolese independence leader, liberator, freedom fighter, Prime Minister and martyr, Nana Patrice Lumumba, Nana Haji Malcolm X, freedom fighter, moral teacher and martyr himself, described him as one of the greatest African leaders that ever walked the African continent. Indeed, Haji Malcolm constantly raised up his life and the liberation struggle of the Congolese people, praising him and their righteous and relentless liberation struggle, citing the Simba, (the namesake of our youth organization, the Simba Wachanga, the Young Lions) as a model of revolutionary resistance by young people. He also condemned the brutal and savage role of the U.S. in the assassination of Nana Lumumba and the reversal of the independence victory the Congolese people had achieved at great cost.

Haji Malcolm rightly recognized and appreciated Nana Patrice’s level of dedication, discipline, sacrifice and achievement, as we say in Kawaida, especially his courage and commitment in the face of death, his refusal under the penalty of death to buck, bow or be the caricature of a man, the colonialists and imperialists wanted him to be. Indeed, like Haji Malcolm would later do himself, Nana Lumumba chose to be a martyr in the liberation struggle of his people rather than compromise on what he called sacred principles of life and struggle.

In his last letter to his beloved wife, co-worker and co-combatant, Nana Pauline Lumumba, while in captivity and about to be murdered, he says, “Neither brutalities, cruelties, nor torture have ever led me to ask for mercy, for I prefer to die with my head high, with unshakable faith and profound confidence in the destiny of my country rather than live in submission and in contempt for sacred principles.” A critical source of the valuable expressions of these qualities and practices can be found in the collection of his writings, interviews, press conferences and letters in the book La Pensée Politique de Patrice Lumumba (The Political Thought of Patrice Lumumba) published by Présence Africaine.

Nana Lumumba spoke of and upheld in practice the sacred principles of love of and faith in the people, unity of the people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a Pan-African unity, especially as a continental project, an unbreakable faith in victory and a willingness to live and die in the pursuit and achievement of freedom. He constantly expresses his love of and commitment to the people and his belief in their capacity to regain their freedom interrupted by a savage genocidal colonialism imposed by Belgium and its European allies, including America. Among his last words in his letter to his beloved wife, Nana Pauline, he expressed faith and certainty in their eventual triumph in securing their independence. He says, “As for me, I know that my country which has suffered so much, will know how to defend its independence and its freedom.” And this faith is still unfolding as the Congolese continue their righteous resistance.

Key to liberation, he taught as all other liberation leaders, was the unity and common struggle of the people in all their diversity. In his speech to the First All African Peoples Conference held in Accra, Ghana, by Nana Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, in 1958, he stresses that the National Congolese Movement (M.N.C.), the liberation party he led, was committed to an inclusive unity and struggle for the Congo and the African continent. Thus, he strove for an “operational unity,” a unity in diversity, but an active, principled, purposeful and productive unity. His intention which was shared by the Accra conference participants was to overcome, avoid and resist that regularly used tactic of the oppressor to divide and conquer, divide and rule. He states that “this tactic, which in the face of the coming into consciousness of the African peoples, adapts itself, taking subtle roundabout means to strike more than ever, to break the will for unity and for liberation of autonomous peoples and to impose economic dependence which is the basis of international imperialism.” Therefore, he said of the M.N.C., “We call upon all our compatriots of all conditions, no matter what their tendencies or their current or past differences, to put in common our energies and our courage to realize our necessary and indispensable joining together without which we cannot be able to affirm ourselves nor make our voices heard, that is to say, the voice of the Congolese people.” In this practice, we say to and show the world “we are united for one same and just cause”: liberation.

It is important to note here that Nana Lumumba rightly reasons that freedom “is a fundamental, natural and sacred right that no doctrine can dispute and no power can extract” from a people or person. And it is of equal importance to bring into focus his position that the Congolese people and all African people are not gaining a freedom given or granted, but are regaining a freedom lost, interrupted and denied by conquest, colonialism, imperialism and the Holocaust of enslavement. Thus, what was lost was not the right of freedom, which is inalienable, but freedom itself which must be regained through righteous and relentless struggle. Here he reaffirms the ancient African Maatian teaching that all humans are born free and that they are endowed by the Creator with certain inalienable rights found in the Husia in the Four Good Deeds of Ra. Thus, he says, “The current dream of Africa, all of Africa, including the Congo, is coming into being as a free continent, independent, in the same way that all other continents of the world, for the Creator has willed that all humans and all peoples be free and equal.”

He tells the oppressor that he must not try to play victim by wrongfully and maliciously labeling “as an anti-white, xenophobic agitator all Africans who condemn the injustices and abuses of which their people are a victim.” For it is the victimizer, the colonialist who has proved himself anti-Black, xenophobic, racist and ultimately anti-human in his oppressive, imperialist and genocidal practices. In fact, he calls the oppressor out, exposing and condemning both his practices and pretensions of being just, civilized and Christian. He says that “Africa in its entirety is irresistibly engaged in a struggle without mercy against colonialism and imperialism.” For the oppressor is using all the savage methods he can devise against us. But we continue to struggle for “We wish to say good-bye to this regime of subjugation and degeneracy which has inflicted so much wrong on us.” And he declares defiantly that “A people who oppresses another is not a people who is civilized or Christian” regardless of its claims to the contrary.

Finally, Nana Lumumba urges the Congolese leaders and people to stop the internecine conflict and wars, to stop letting the imperialists manipulate them and reverse the people’s hard-won independence. The overwhelming need, he says, is to remember the central objective which is to free ourselves, harness our resources “in a common effort to create a national economy which allows us to rapidly improve the life conditions for all the people.” This means the oppressor cannot be our teacher, tutor, sponsor or manipulator. For as Nana Lumumba defiantly declares, “We are Africans and wish to remain so. We have our own philosophy, our own customs, our own traditions which are as noble as those of other nations.” And thus, as always, we must draw from these our own distinct ways to practice freedom, serve our people, engage the world, and make our own unique contribution to the forward flow of human history and the achievement of an expansive and inclusive good in the world.