Petrocaribe Protests in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. October 2018. Photo: Patrice Douge, Haitian Times.

In 2015 and 2016, backed by the international community, political and economic actors made a Faustian bargain in the name of “stability.”

By Jake Johnston, Haitian Times —

The following is a lightly edited compilation of a thread posted on Twitter by Jake Johnston, International Research Associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) and lead author of the Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch blog.

You can draw a pretty straight line from the last electoral process to the current unrest in Haiti. Building for months, and frankly years, the country has now been shut down for five days as tensions – and violence – increase, threatening President Jovenel Moise’s mandate.

In 2015 and 2016, backed by the international community, political and economic actors made a Faustian bargain in the name of “stability.” They decided to allow fraudulent and violence-plagued legislative elections to stand, and rerun them at the presidential level.

The failure of that analysis is evidenced by the situation in Haiti today. In truth, it’s been international policy for more than a decade. Keep a lid on things, while sustaining the unsustainable status quo.

The incoming legislature was stacked full of “legal bandits” and to ensure a continuation of the Michel Martelly/PHTK government, Moise allied with some of the country’s most nefarious political actors. As I wrote at the time:

Will this strategy of elite alliances and local influence maintain right-wing rule in Haiti? Three decades of near-constant foreign intervention and the failures of Haiti’s traditional political class have weakened and divided the country’s once strong and united democracy movement. Elite control, at least in the short term, is now all but ensured.

But the foundation for this “stability” has been built with kindling. With so many excluded from their country’s politics, the viability of Haiti’s electoral democracy as a path toward constitutional order and stability has been diminished. More than two hundred years since Haitian independence, the struggle for freedom will find other expressions.

Senator Youri Latortue, a former ally of the president who has turned into a leading critic and “anti-corruption champion,” owes his seat in the legislature to dirty dealing and corruption in his home department of the Artibonite:

To secure a first-round win, a candidate must receive at least 50 percent of the vote, or a 25-percent lead over the second place finisher. Latortue had neither. But not only did the court reintroduce tally sheets to get over the 70-percent barrier, it applied a different calculation method to allow Latortue to advance to the second round. Despite being completely in conflict with the regulations and interpretation put forth by the CEP, Latortue advanced based on the court’s ruling while receiving only 27 percent of the vote.

After the decision, an anonymous member of the CEP spoke to Haiti’s leading daily,Le Nouvelliste, explaining that the departmental electoral court had no jurisdiction to put excluded tally sheets back into the count. “Yes, there was influence peddling, bargaining,” the member told the paper. “With advisors clearly at the service of power and other interests, it is difficult to guarantee elections and the credibility of results.”

Moise received most of the votes in the presidential election rerun. However, with less than 20 percent voter turnout and a process that was deeply compromised, it was crazy to believe that the election would lead to stability.

When the #KoteKobPetrocaribea protests began this past August, most analysts viewed the movement as little more than a flash — a temporary spasm that was driven more by politics than citizen frustration.

But it should have been more accurately viewed as the manifestation of tremendous anger built up at a political and economic system that failed the people.

Again, the analysis of the government and its international allies was faulty. Believing the cries of the population could be ignored and a political solution reached, the government failed to adequately respond to the demands emanating from the street.

It didn’t help that the president built his campaign around a company that was a commercial failure and was found to have received Petrocaribe funds during the presidential campaign.

The fact remains, however, that Agritrans has never made a profit. Since Moïse launched his presidential campaign with that first shipment, only one additional container has left port, and it was more than two years ago, in April 2016.

As a free-trade zone, Agritrans is legally required to export 70 percent of its production. In 2014 the company signed a long-term deal with a German company, Port International, which called for the shipment of up to 60 containers per week. Agritrans has claimed that the replanting effort was made in coordination with their international partner, but the company provided a contradictory view.

Mike Port, an official with the company, confirmed to me that there had been no recent communication with Agritrans. “We had just 2 shipments and it seems that due to unknown reasons Agritrans was not in a position to establish the relationship we wanted,” Port wrote to me via e-mail in February. “We lost contact during and after elections.”

Now, facing generalized unrest, and with each day showing the government’s lack of control over the country, the people and the economy, the situation is approaching the brink. Enter the international community, again.

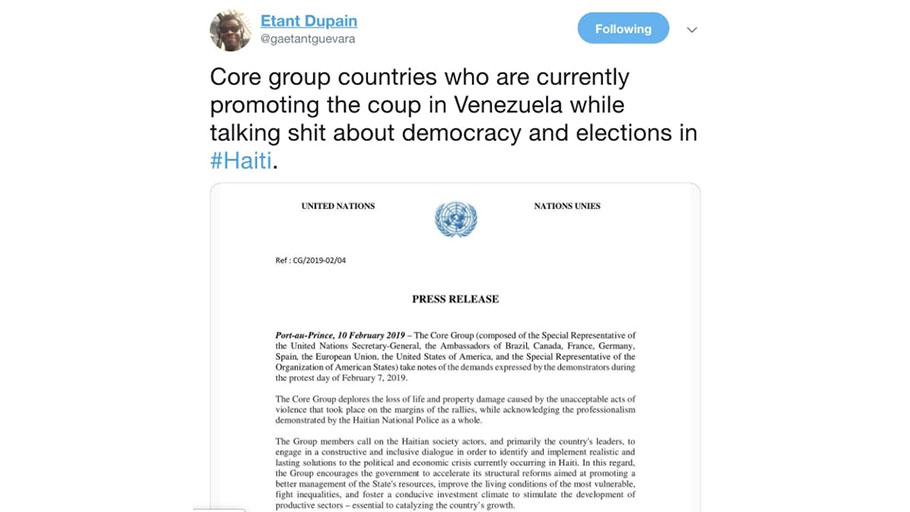

The Core Group — composed of the Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General, the Ambassadors of Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, the European Union, the United States of America, and the Special Representative of the Organization of American States — in its customary diplomatic language, once again called for elections as a way out of the crisis. Though the government surely viewed the statement as support, reading between the lines, it was perhaps the most critical statement I can remember.

Nevertheless, it shows the continued naivete of those in the international community. If elections are not held this coming October, then the terms of parliament will expire and, come 2020, the president may be ruling by decree.

But thinking that elections will resolve the current crisis is patently absurd. As one diplomat recently conceded, rather than releasing tension, elections have the opposite effect in Haiti. It is the legal bandits who would once again dominate in this environment.

(Not to mention the hypocrisy of the Core Group statement).

None of which seems to allow an easy way out of the current situation. The economy is crumbling, and the government has nowhere near the resources to address it. The president’s calls for dialogue have fallen on deaf ears. Reshuffling ministers won’t do anything.

None of which seems to allow an easy way out of the current situation. The economy is crumbling, and the government has nowhere near the resources to address it. The president’s calls for dialogue have fallen on deaf ears. Reshuffling ministers won’t do anything.

And who would the government dialogue with? Yes, the political opposition smells blood, but no single actor has control over the streets today. And who among the country’s political and civic leaders has the credibility to lead such a process?

The strategy of the Haitian government appears to be hunker down and hope this all just goes away. In the meantime, the situation for millions of Haitians will continue to deteriorate, caught between political violence, government ineptitude, and the ever-increasing cost of living.

I believe what we are witnessing is the collapse of a system. A system that has failed the Haitian people. There are no more quick fixes; there are no more internationally devised compromises to paper over the reality.

I fear that things will get worse before they get better.

The hope? A new generation of leaders who have yet to fully emerge, but undoubtedly will be the only ones able to lead their country forward. Who among the discredited political class will have the courage to step aside and empower them?

The Haitian Times was founded in 1999 as a weekly English language newspaper based in Brooklyn, NY.The newspaper is widely regarded as the most authoritative voice for Haitian Diaspora.