By Ben Becker –

What we now know as Memorial Day began as “Decoration Day” in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. Civil War. It was a tradition initiated by former slaves to celebrate emancipation and commemorate those who died for that cause.

These days, Memorial Day is arranged as a day “without politics”—a general patriotic celebration of all soldiers and veterans, regardless of the nature of the wars in which they participated. This is the opposite of how the day emerged, with explicitly partisan motivations, to celebrate those who fought for justice and liberation.

The concept that the population must “remember the sacrifice” of U.S. service members, without a critical reflection on the wars themselves, did not emerge by accident. It came about in the Jim Crow period as the Northern and Southern ruling classes sought to reunite the country around apolitical mourning, which required erasing the “divisive” issues of slavery and Black citizenship. These issues had been at the heart of the struggles of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

To truly honor Memorial Day means putting the politics back in. It means reviving the visions of emancipation and liberation that animated the first Decoration Days. It means celebrating those who have fought for justice, while exposing the cruel manipulation of hundreds of thousands of U.S. service members who have been sent to fight and die in wars for conquest and empire.

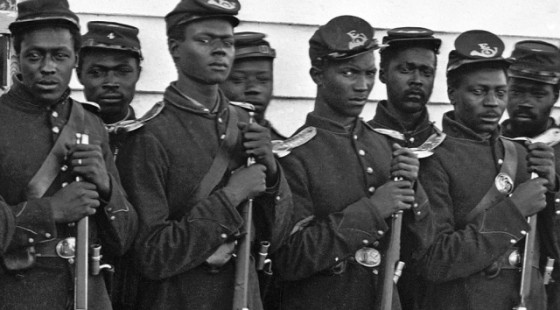

As the U.S. Civil War came to a close in April 1865, Union troops entered the city of Charleston, S.C., where four years prior the war had begun. While white residents had largely fled the city, Black residents of Charleston remained to celebrate and welcome the troops, who included the TwentyFirst Colored Infantry. Their celebration on May 1, 1865, the first “Decoration Day,” later became Memorial Day.

Yale University historian David Blight retold the story:

During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the planters’ horse track, the Washington Race Course and Jockey Club, into an outdoor prison. Union soldiers were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of exposure and disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand. Some 28 black workmen went to the site, re-buried the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”Then, black Charlestonians in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged an unforgettable parade of 10,000 people on the slaveholders’ race course. The symbolic power of the low-country planter aristocracy’s horse track (where they had displayed their wealth, leisure, and influence) was not lost on the freed people. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

At 9 a.m. on May 1, the procession stepped off led by 3,000 black schoolchildren carrying armloads of roses and singing “John Brown’s Body.” The children were followed by several hundred black women with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses.

Then came black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantry and other black and white citizens. As many as possible gathered in the cemetery enclosure; a childrens’ choir sang “We’ll Rally around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and several spirituals before several black ministers read from scripture.

Blight’s award-winning Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001) explained how three “overall visions of Civil War memory collided” in the decades after the war.

The first was the emancipationist vision, embodied in African Americans’ remembrances and the politics of Radical Reconstruction, in which the Civil War was understood principally as a war for the destruction of slavery and the liberation of African Americans to achieve full citizenship.

The second was the reconciliationist vision, ostensibly less political, which focused on honoring the dead on both sides, respecting their sacrifice, and the reunion of the country.

The third was the white supremacist vision, which was either openly pro-Confederate or at least despising of Reconstruction as “Black rule” in the South.

Over the late 1800s and the early 1900s, in the context of Jim Crow and the complete subordination of Black political participation, the second and third visions largely combined. The emancipationist version of the Civil War, and the heroic participation of African Americans in their own liberation, was erased from popular culture, the history books and official commemoration.

In 1877, the Northern capitalist establishment decisively turned their backs on Reconstruction, striking a deal with the old slavocracy to return the South to white supremacist rule in exchange for the South’s acceptance of capitalist expansion. This political and economic deal was reflected in how the war was commemorated. Just as the reunion of the Northern and Southern ruling classes was based on the elimination of Black political participation, the way the Civil War became officially remembered—through the invention of Memorial Day—was based on the elimination of the Black veteran and the liberated slave.

The spirit of the first Decoration Day—the struggle for Black liberation and the fight against racism—has unfortunately been whitewashed from the modern Memorial Day.

As Blight explains, “With time, in the North, the war’s two great results—black freedom and the preservation of the

Union—were rarely accorded equal space. In the South, a uniquely Confederate version of the war’s meaning, rooted in resistance to Reconstruction, coalesced around Memorial Day practice.” (“Race and Reunion,” p. 65)

In the statues, anniversary parades and popular magazines, the Civil War was portrayed as an all-white affair, a tragic conflict between brothers. To the extent the role of slavery was allowed in these remembrances, Lincoln was typically portrayed as the beneficent liberator standing above the kneeling slave.

The mere image of the fighting Black soldier pierced through this particular “memory,” which in reality was a collective and forced “forgetting” of the real past. Portraying the rebellious slave or Black soldier would unmask the Civil War as a life-and-death struggle against slavery, a true social revolution, and a reminder of the political promises that had been betrayed.

While African Americans and white radicals continued to uphold the emancipationist remembrance of the Civil War during the following decades—as exemplified by W.E.B. DuBois’ landmark “Black Reconstruction”—this interpretation was effectively silenced in the “respectable” circles of academia, mainstream politics and popular culture. The white supremacist and reconciliationist retelling of the war and Reconstruction was only overthrown in official academic circles in the 1950s and 1960s as the Civil Rights movement shook the country to its core, and more African Americans fought their way into the country’s universities.

While historians have gone a long way to expose the white supremacist history of the Civil War and uncover its revolutionary content, the spirit of the first Decoration Day—the struggle for Black liberation and the fight against racism—has unfortunately been whitewashed from the modern Memorial Day.

So let’s use Memorial Day weekend to honor the fallen fighters for justice worldwide, to speak plainly about this country’s historic crimes, and rededicate ourselves to take on those of the present.

This article originally appeared in LiberationNews.org