Many will tell her story, but she told

her story — and ours — best.

The name Assata Shakur is enshrined in the student center at The City College of New York (CCNY), where it is combined with that of Puerto Rican activist Guillermo Morales. Her presence was felt even after she had left the campus, not too far from my office and classroom. In her memoir, Assata: An Autobiography, however, she explained that she learned more from one night with fellow Panthers Dhoruba Bin-Wahad, Jamal Joseph, and Michael “Cetewayo” Tabor than she did in a semester at the college.

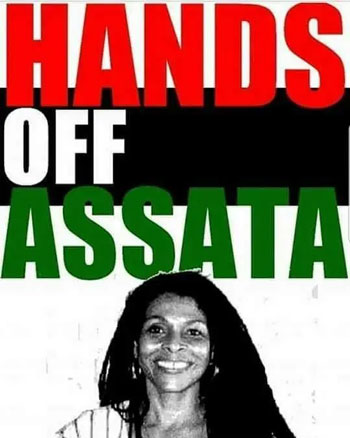

Assata Shakur Credit: New Jersey State Police

The freedom fighter—wanted by the FBI but celebrated by her people and others everywhere—died on Thursday at 78, according to an announcement by the Cuban government. She died in Havana of health complications and advanced age, the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated.

She had been living in exile in Cuba since escaping from jail in 1979, having been convicted and imprisoned for the killing of a New Jersey state trooper in 1973. Upon her arrival in the island nation that she came to love, she was granted political asylum and quickly identified with the land and the people, who welcomed her with open arms.

Born Joanne Deborah Byron (Chesimard) on July 16, 1947, in Flushing, Queens, she grew up in New York City and Wilmington, N.C. Her parents divorced when she was a baby, and she was raised by her grandmother and, particularly, her aunt, Evelyn Williams, the legal scholar who later served as her attorney. After attending the Borough of Manhattan Community College and City College—from which she never graduated—her life took a tumultuous, radical turn as a member of the Black Panther Party and subsequently the Black Liberation Army (BLA).

Despite her birth name, most of the world came to know her as Assata Olugbala Shakur, an identity she adopted that was part Swahili, Yoruba, and Arabic, translating to “she who struggles,” “savior,” and “thankful one.”

Testament

In her memoir, Assata: An Autobiography (1987), she provides riveting context, beginning with this declaration: “I am a Black revolutionary, and that makes me a part of the Black Liberation Army,” she wrote. “The pigs (police) have used their newspapers and TVs to paint the Black Liberation Army as vicious, brutal, mad-dog criminals. They have called us gangsters as [they did] John Dillinger and Ma Barker. It should be clear, it must be clear to anyone who can think, see, or hear, that we are victims…”

She continued by noting that “the real criminals are Nixon and his crime partners” who have “murdered hundreds of Third World brothers and sisters in Vietnam, Cambodia, Mozambique, Angola, and South Africa.” She then observed that “we did not murder Martin Luther King, Jr., Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, George Jackson, Nat Turner, James Chaney and countless others.”

This kind of background was a far cry from her early years in Wilmington, when, as she related, “I was supposed to be a child version of a goodwill ambassador out to prove that Black people were not stupid or dirty or smelly or uncultured.”

Conversely, another one of her attorneys, Lennox Hinds, whom she met in 1973, recalled her interrogation in the foreword to her memoir: “…She lay in the hospital, close to death, handcuffed to her bed, while state, local, and federal police attempted to question her.”

But before these moments of intense interrogation, there was a story—one that stands as a testament to who Assata was as a woman and a hero.

In the autobiography, which has a cinematic quality, a mixture of flashbacks and foreshadowing, Hinds does a masterful job filling in the blanks and connecting the drama of her life. He explained that Assata, Sundiata Acoli, and Zayd Malik Shakur were traveling south on the New Jersey Turnpike in a white Pontiac when they were stopped by a state trooper. The trooper spotted the car because of a defective taillight and followed them for a couple of miles.

Suddenly, as Assata recounted, “there were lights and sirens. Zayd was dead…The car spun around me. In the background I could hear what sounded like gunfire. But I was fading and dreaming,” she vaguely recalled. She said she was in and out of consciousness, only hearing the words “Is she dead yet?”

Thus began her horrendous encounter with law enforcement officers, something she compared to a terrible nightmare. Things became even more convoluted when she learned she had been charged in the murder of the New Jersey trooper. Most critical in the litany of charges against Assata was one that asserted she “unlawfully and illegally and forcibly take from the person of New Jersey State Trooper Werner Foerster a .38 caliber revolver by violence, to wit, by shooting, and slaying and killing the same…in violation” of New Jersey law.

“Half the charges, I don’t even understand,” Assata said at the time. She interrupted the proceedings: “I don’t have a lawyer. I would like to have a lawyer.” She was ignored, and the trial proceedings resumed.

Part of her defense was the fact that she was shot several times herself and was thus incapacitated and unable to kill anyone. She recounted portions of this scenario during an appearance on Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now.

“I was captured in New Jersey in 1973, after being shot with both arms held in the air, and then shot again from the back. I was left on the ground to die, and when I did not, I was taken to a local hospital where I was threatened, beaten, and tortured. In 1977, I was convicted in a trial that can only be described as a legal lynching.

“In 1979,” she continued. “I was able to escape with the aid of some of my comrades. I saw this as a necessary step, not only because I was innocent of the charges against me, but because I knew that in the racist legal system in the United States, I would receive no justice. I was also afraid that I would be murdered in prison.’ Five years later, she fled to Cuba and was granted political asylum by Fidel Castro.”

Freedom Song

The details of her escape are not disclosed, in keeping with her notion of a cimarrón—a Spanish term which refers to a runaway slave, as she called herself. Nor is it clear how she became pregnant during her incarceration ordeal and later gave birth to a daughter, Kakuya. Among the things she was willing to discuss was her time in Cuba, which unfolds beautifully in the documentary Eyes of the Rainbow, by Gloria Rolando in 1997.

There are scenes of the lush tropical setting that surprised Assata, much like the African culture, particularly the music and dance; there are also several scenes of women who resembled her swirling rhythmically to a drum choir.

Even as she was peacefully sequestered in Cuba, the U.S. government continued to seek her arrest, making her the first woman placed on a Most Wanted List and later adding a $2 million reward for her capture. The Amsterdam News joined a global campaign declaring “Hands off Assata” in 2005. In 2013, she was added to the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list.

But the terrorist designation was too weak to define Assata.

But the terrorist designation was too weak to define Assata.

Upon learning of her transition, Bin-Wahad wrote: “Assata was Our Freedom Fighter. A Soldier in the BLA, a Member of the Original Black Panther Party when it defended the existential integrity of the Black Community. She was a stalwart in our Resistance to State sanctioned murder of Black people by the Police and White militia’s in Blue costumes. She’s our 20th century Sojourner Truth. Our anti-Imperialist Harriet Tubman in a protracted war imposed on African people since 1619.”

Her final words in her autobiography typified her revolutionary commitment, her defiance of racism, imperialism, and the quest for total liberation.

“How much we had gone through. Our fight had started on a slave ship years before we were born,” she wrote. “Venceremos (we shall overcome), my favorite word in Spanish, crossed my mind. Ten million people had stood up to the monster. Ten million people, only ninety miles away. We were here together in their land, my small family, holding each other after so long. There was no doubt about it, our people would one day be free. The cowboys and bandits didn’t own the world.”

Source: New Amsterdam News