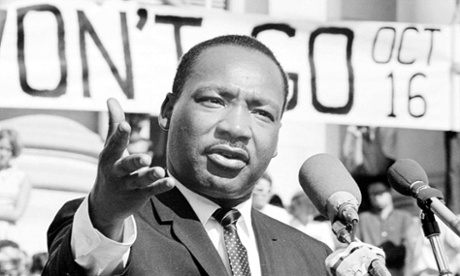

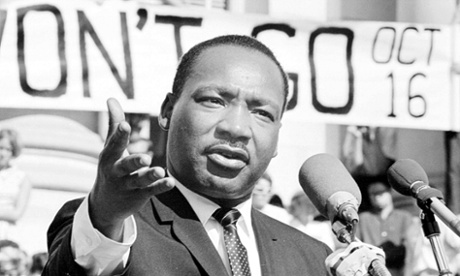

In 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.talked about the “bad check” marked “insufficient funds” that America had given black Americans. It hasn’t been paid. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images

In 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.talked about the “bad check” marked “insufficient funds” that America had given black Americans. It hasn’t been paid. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives / Getty ImagesEven before its online debut on Thursday, social media was ablaze for days in anticipation of this month’s Atlantic cover story arguing in favor of reparative payments to African-Americans for state-sanctioned slavery and segregation. To add to the hype, the magazine publicized “The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates with a rare trailer promoting the story (which hits newsstands on 27 May).

Reaction to the piece has been mixed (to say the least) but it appears to be having at least part of the author’s intended effect: to get people’s attention, and to begin a national conversation about the lingering effects of racism and oppression in America.

Coates lays out his argument over 17 pages, spanning – as the cover boldly declares in black, white and red – “250 years of slavery, 90 years of Jim Crow, 60 years of separate but equal and 35 years of state-sanctioned redlining”. He admits that he is not starting a new argument, but he does attempt a new approach by framing reparations not just as a financial debt to be paid, but as an emotional and psychological one necessary to begin healing the entire nation (and not just black Americans).

And while Coates mentions the role of the government in reparations – focusing attention on the languishing legislation proposed by Michigan Democratic Rep. John Conyers, for example – he recognizes, as others who attempted to affect change throughout the history of this country have, that the moral will of all Americans must also be part of the solution.

The only thing missing from this conversation about racial healing – which may or may not ultimately include reparations – is a door for both black and white Americans to walk through.

In his address at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. told the crowd of the “bad check” marked “insufficient funds” that America had given black Americans, challenging the country to deliver on its promise of freedom and justice for all. While he wasn’t talking about reparations per se, King was appealing to the federal government and the nation’s conscience about what he believed African-Americans were owed after centuries of slavery and segregation.

Half a century later, that check has still not been cashed, and the conversation about what – or if – anything should be done for the descendants of those who endured the horrors of those eras has been muted in favor of advancing a supposedly “post-racial” society that deems the effects of slavery and Jim Crow extinct or no longer relevant.

Interestingly, Coates’s story launched the same day as the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. The broad domestic agenda sought, in part, to eradicate poverty and injustice “in our time” as just the beginning of “abundance and liberty for all”.

It also comes in the midst of our nation’s remembrance of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War – a milestone during which talk of race has been largely and strikingly absent. With only a year left to mark the sesquicentennial of its conclusion, ignoring the call of people like Coates means that we run the risk of missing an opportunity to begin this dialogue in our lifetimes.

It is for this reason that it is so important – even imperative – that this conversation starts with an African-American writer telling this story in a legacy, mainstream publication like The Atlantic. The combination of the two adds weight and validity to the argument – and makes reparations harder to dismiss, yet again, as “crazy talk”. It does no good to have only black Americans in conversation with each other about topics of race. (I suspect that The Atlantic got a lot more black readers this week, and that white readers were introduced to a topic they likely have not fully considered until now.)

“The Case for Reparations” is a bold beginning to the greater conversation we must have on the damages wrought by racism that still need repair in our nation. That anyone in 2014 would be pleading, as Coates is, to simply talk honestly about the implications behind centuries of proven history of one group oppressing another, is astonishing.

More remarkable still could be what happens as a result of him asking the question.