By Ta-Nehisi Coates

Tulsa burns in the race riots of 1921. Wikimedia

There have been a number of useful entries in the weeks since Senator Bernie Sanders declared himself against reparations. Perhaps the most clarifying comes from Cedric Johnson in a piece entitled, “An Open Letter To Ta-Nehisi Coates And The Liberals Who Love Him.” Johnson’s essay offers those of us interested in the problem of white supremacy and the question of economic class the chance to tease out how, and where, these two problems intersect. In Johnson’s rendition, racism, in and of itself, holds limited explanatory power when looking at the socio-economic problems which beset African Americans. “We continue to reach for old modes of analysis in the face of a changed world,” writes Johnson. “One where blackness is still derogated but anti-black racism is not the principal determinant of material conditions and economic mobility for many African Americans.”

Johnson goes on to classify racism among other varieties of -isms whose primary purpose is “to advance exploitation on terms that are most favorable to investor class interests.” From this perspective, the absence of specific anti-racist solutions from Bernie Sanders, as well as his rejection of reparations, make sense. By Johnson’s lights, racism is a secondary concern, and to the extent that it is a concern at all, it is weapon deployed to advance the interest of a plutocratic minority.

At various points in my life, I have subscribed to some version of Johnson’s argument. I did not always believe in reparations. In the past, I generally thought that the problem of white supremacy could be dealt through the sort of broad economic policy favored by Johnson and his candidate of choice. But eventually, I came to believe that white supremacy was a force in and of itself, a vector often intersecting with class, but also operating independent of it.

Nevertheless, my basic feelings about the kind of America I want to live have not changed. I think a world with equal access to safe, quality, and affordable education; with the right to health care; with strong restrictions on massive wealth accumulation; with guaranteed childcare; and with access to the full gamut of birth-control, including abortion, is a better world. But I do not believe that if this world were realized, the problem of white supremacy would dissipate, anymore than believe that if reparations were realized, the problems of economic inequality would dissipate. In either case, the notion that one solution is the answer to the other problem is not serious policy. It is a palliative.

Unfortunately, palliatives are common these days among many of us on the left. In a recent piece, I asserted that western Europe demonstrated that democratic-socialist policy, alone, could not sufficiently address the problem of white supremacy. Johnson strongly disagreed with this:

Coates’s sweeping mischaracterization diminishes the actual impact that social-democratic and socialist governments have historically had in improving the labor conditions and daily lives of working people, in Europe, the United States, and for a time, across parts of the Third World.

There is not a single word in this response relating to race and racism in Western Europe or anything remotely closely to it. Instead, Johnson proposes to bait with race, and then switch to class. He swaps “labor conditions and daily lives of working people” in for “victims of white supremacy” and prays that the reader does not notice. Indeed, one might just as easily note that the advance of indoor plumbing, germ theory, and electricity have improved “the labor conditions and daily lives of working people,” and this would be no closer to actual engagement.

This pattern—strident rhetoric divorced from knowable fact—marks Johnson’s argument. Reparations, he tells us, do not emerge from the “felt needs of the majority of blacks,” a claim that is hard to square with the fact that a majority of blacks support reparations. Instead, he argues, the claim for reparations emerges from a cabal of “anti-racist liberals” and “black elites” seeking to make a “territorial-identitarian claim for power.” In fact, the reparations movement runs the gamut from the victims of Jon Burge, to those targeted by North Carolina’s eugenics campaign, to those targeted by the same campaign in Virginia, to those targeted by “Massive Resistance” in the same state, to the descendants of those devastated by the Tulsa pogrom. Are the black people of Tulsa who suffered aerial bombing at the hands of their own government“black elites” in pursuit of “territorial-identitarian claim?” Or are they something far simpler—people who were robbed and believe they deserve to be compensated?

Johnson denigrates recompense by asserting that the demands for reparations have not “yielded one tangible improvement in the lives of the majority of African Americans.” This is also true of single-payer health care, calls to break up big banks, free public universities, and any other leftist policy that has yet to come to pass. For a program to have effect, it has to actually be put in effect. Why would reparations be any different?

But ultimately, Johnson doesn’t reject reparations because he doesn’t think they would work, but because he doesn’t believe specific black injury through racism actually exists. He favors a “more Marxist class-oriented analysis” over the notion of treating “black poverty as fundamentally distinct from white poverty.” Johnson declines to actually investigate this position and furnish evidence—even though such evidence is not really hard to find.

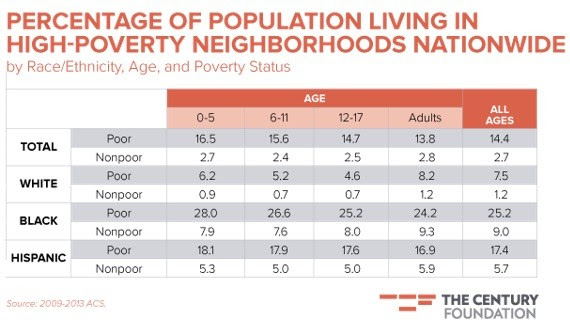

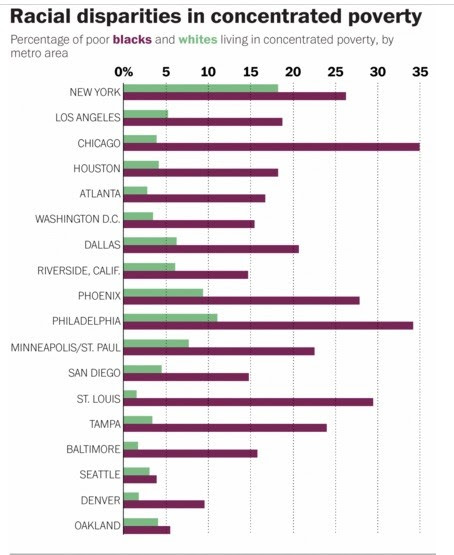

Courtesy of Emily Badger, this is a chart of concentrated poverty in America—that is to say families which are both individually poor and live in poor neighborhoods. Whereas individual poverty deprives one of the ability to furnish basic needs, concentrated poverty extends out from the wallet out to the surrounding institutions—the schools, the street, the community center, the policing. If individual poverty in America is hunger, neighborhood poverty is a famine. As the chart demonstrates, the black poor are considerably more subject to famine than the white poor. Indeed, so broad is this particular famine that its reach extends out to environs that most would consider well-nourished.

As the chart above demonstrates, neighborhood poverty threatens both black poor and nonpoor families to such an extent that poor white families are less likely to live in poor neighborhoods than nonpoor black families. This is not an original finding. The sociologist Robert Sampson finds that:

….racial differences in neighborhood exposure to poverty are so strong that even high-income blacks are exposed to greater neighborhood poverty than low-income whites. For example, nonpoor blacks in Chicago live in neighborhoods that are nearly 30 percent in poverty—traditionally the definition of “concentrated poverty” areas—whereas poor whites lives in neighborhoods with 15 percent poverty, about the national average.*

In its pervasiveness, concentration, and reach across class lines, black poverty proves itself to be “fundamentally distinct” from white poverty. It would be much more convenient for everyone on the left if this were not true—that is to say if neighborhood poverty, if systemic poverty, menaced all communities equally. In such a world, one would only need to craft universalist solutions for universal problems.

But we do not live that world. We live in this one:

Patrick Sharkey “Neighborhoods And The Black White Mobility Gap”

Patrick Sharkey “Neighborhoods And The Black White Mobility Gap”

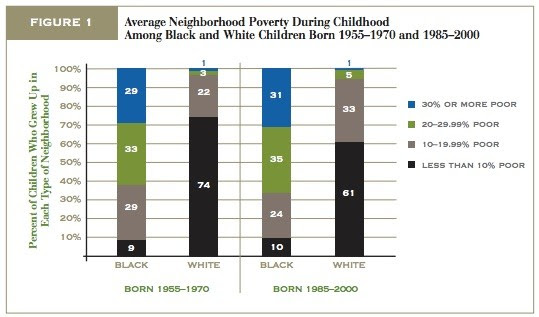

This chart by sociologist Patrick Sharkey quantifies the degree to which neighborhood poverty afflicts black and white families. Sociologists like Sharkey typically define a neighborhood with a poverty rate greater than 20 percent as “high poverty.” The majority of black people in this country (56 percent) live in high-poverty neighborhoods. The vast majority of whites (94 percent) do not. The effects of this should concern anyone who believes in a universalist solution to a particular affliction. According to Sharkey:

Neighborhood poverty alone, accounts for a greater portion of the black-white downward mobility gap than the effects of parental education, occupation, labor force participation, and a range of other family characteristics combined.

No student of the history of American housing policy will be shocked by this. Concentrated poverty is the clear, and to some extent intentional, result of the segregationist housing policy that dominated America through much of the 20th century.

But the “fundamental differences” between black communities and white communities do not end with poverty or social mobility.

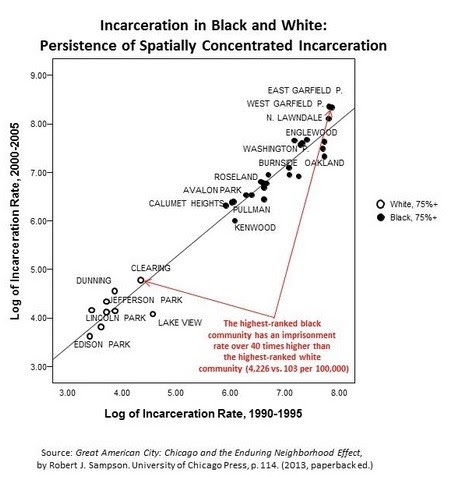

In the chart above, Sampson plotted the the incarceration rate in Chicago from the onset imprisonment boom to its height. As Sampson notes, the incarceration rate in the most afflicted black neighborhood is 40 times worse than the incarceration rate in the most afflicted white neighborhood. But more tellingly for our purposes, incarceration rates for white neighborhoods bunch at the lower end, while incarceration rates for black neighborhoods bunch at the higher end. There is no gradation, nor overlap between the two. It is almost as if, from the perspective of mass incarceration, black and white people—regardless of neighborhood—inhabit two “fundamentally distinct”worlds.

The pervasive and distinctive effects of racism are viewable at every level of education from high school drop-outs (see pages 13-14 of this Pew report, especially) to Ivy league graduates. I strongly suspect that if one were to investigate public-health outcomes, exposure to pollution, quality of public education or any other vector relating to socio-economic health, a similar pattern would emerge.

Such investigations are of little use to Johnson, who prefers ideas over people, and jargon divorced of meaningful investigation. The “black managerial elite” are invoked without any attempt to quantify their numbers and power. “Institutional racism” is presented as a figment, without actually defining what it is, and why, in Johnson’s mind, it is insignificant. “Black plunder” is invoked in Chicago, with no effort to examine its effects or compare it to “white plunder.” Johnson tells us that “universal social policies” and an expanded “public sector” built the black middle class. He seems unaware that the same is true of the “white middle class.” A useful question might arise from such awareness: Has the impact of “universalist social policies” been equal across racial lines? Johnson can not be bothered with such questions as he is preoccupied with —in his own words—“solidarity.”

I am not opposed to solidarity, in and of itself, but I would have its basis made clear. When an argument is divorced of this clarity, then deflection, subject-changing, abstraction, and head-fakes—as when Johnson exchanges“laborers” for the victims of white supremacy—all become inevitable.

Bombast, too. In Johnson’s rendition, black writers who trouble his particular “solidarity” are not sincerely disagreeing with his ideas, they are assuaging “white guilt” and doing the dirty work of interpreting black people for “white publics.” Johnson lobs this charge as though he is not himself interpreting for white publics, as though he were holding forth from the offices of The Amsterdam News. And then he lobs a good deal more:

…Coates’s latest attack on Sanders, and willingness to join the chorus of red-baiters, has convinced me that his particular brand of antiracism does more political harm than good, further mystifying the actual forces at play and the real battle lines that divide our world.

This not the language of debate. It is the vocabulary of compliance. In this way, a strong and important disagreement on the left becomes something darker. Critiquing the policies of a presidential candidate constitutes an “attack.” A call for intersectional radicalism is “red-baiting.” And the argument for reparations does “more political harm than good.”

The feeling is not mutual. I think Johnson’s ideas originate not in some diabolical plot, but in an honest and deeply held concern for the plundered peoples of the world. Whatever their origin, there is much in Johnson’s response worthy of study, and much more which all who hope for struggle across the manufactured line of race might learn from. Johnson’s distillation of the Readjuster movement, his emphasis on the value of the postal service and public-sector jobs, and his insistence on telling a broader story of housing and segregation add considerable value to the present conversation. His insistence that airing arguments to the contrary is harmful does not.

It is not even that a solidarity premised on the suppression of debate—a solidarity of ignorance—is wrong in and of itself, thought it is. It is that a solidarity of ignorance blinds one to complicating factors:

Social exclusion and labor exploitation are different problems, but they are never disconnected under capitalism. And both processes work to the advantage of capital. Segmented labor markets, ethnic rivalry, racism, sexism, xenophobia, and informalization all work against solidarity. Whether we are talking about antebellum slaves, immigrant strikebreakers, or undocumented migrant workers, it is clear that exclusion is often deployed to advance exploitation on terms that are most favorable to investor class interests.

No. Social exclusion works for solidarity, as often as it works against it. Sexism is not merely, or even primarily, a means of conferring benefits to the investor class. It is also a means of forging solidarity among “men,” much as xenophobia forges solidarity among “citizens,” and homophobia makes for solidarity among “heterosexuals.” What one is is often as important as what one is not, and so strong is the negative act of defining community that one wonders if all of these definitions—man, heterosexual, white—would evaporate in absence of negative definition.

That question is beyond my purview (for now). But what is obvious is that the systemic issues that allowed men as different as Bill Cosby and Daniel Holtzclaw to perpetuate their crimes, the systemic issues which long denied gay people, no matter how wealthy, to marry and protect their families, can not be crudely reduced to the mad plottings of plutocrats. In America, solidarity among laborers is not the only kind of solidarity. In America, it isn’t even the most potent kind.

The history of the very ideas Johnson favors evidences this fact. At every step, “universalist” social programs have been hampered by the idea of becoming, and remaining, forever white. So it was with the New Deal. So it is with Obamacare. So it would be with President Sanders. That is not because the white working class labors under mass hypnosis. It is because whiteness confers knowable, quantifiable privileges, regardless of class—much like “manhood” confers knowable, quantifiable privileges, regardless of race. White supremacy is neither a trick, nor a device, but one of the most powerful shared interests in American history.

And that, too, is solidarity.

(

(