White nationalists parade through the U. of Virginia campus on the eve of the “Unite the Right” rally that left three people dead. Are colleges unconsciously endorsing the white victimhood that gives rise to such protests?

By Marcia Chatelain, The Chronicle of Higher Education —

“They’re just ignorant.”

That’s what my mother and other grown-ups would tell me when I was upset about the racism I encountered at school.

I was that lone black girl in the class photo from first through eighth grades. I grew up to become one of the few black women in my high school, in the college auditorium lectures, in my graduate seminars, and now, on the dais at university convocations. When boys in my class called me “Aunt Jemima,” it was ignorance. When a classmate greeted me to the first week of college with complaints about scholarships for students of color, it was ignorance. And I suppose when I was mistaken for the coat-check attendant at my colleague’s book party, ignorance must have snuck onto the guest list.

Yet, over the years, I’ve found that the learned racist can be the most dangerous one.

This week, as we gain more insights into the people, including a terrorist, who participated in the “Unite the Right” rally at the University of Virginia, we are learning that some of them are college students or college-educated. The mouthpiece for this movement, Richard Spencer, for instance, has attended some of the finest universities in the world, including UVa, Duke, and the University of Chicago. On campuses from Towson University in Maryland to the University of Nevada at Reno, students affiliated with white-nationalist organizations have troubled their fellow students and administrators by distributing racist fliers, inviting white supremacists to lecture on campus, and establishing student clubs dedicated to preserving something they call white heritage.

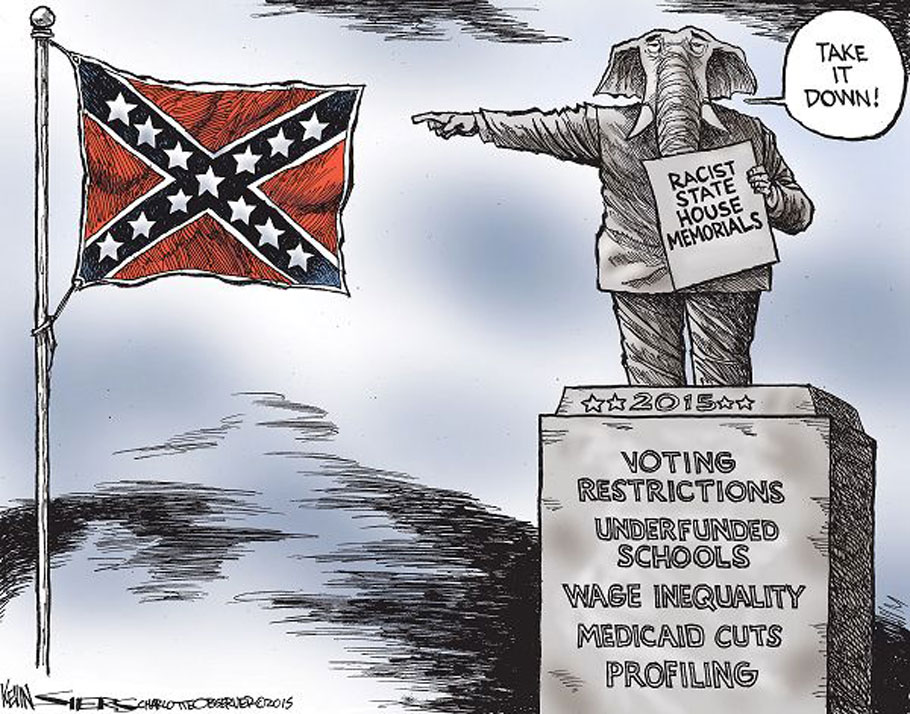

For the most part, university officials have responded with statements declaring that hate has no place on campus or affirming free speech. But these carefully drafted responses rarely speak to the myriad ways that college campuses are complicit in encouraging and emboldening budding white nationalists. The basis of the white-nationalist anxiety is that inclusion means erasure, that they are fighting a mass invasion of outsiders into institutions that rightfully belong to whites. They inspire victimhood among their adherents by ignoring the evidence of the durability of white supremacy in the United States, including on our campuses. Most faculty, staff, and administrators abhor this thinking and ideology, but in my experience, they often tacitly endorse ideas that may help create little Richard Spencers.

College students are just one click away from websites and online forums that allow white nationalists to bring chaos onto campus. As we prepare for the academic year, I hope we can reflect on how some of our practices — subtle and overt — may be perceived by students who are vulnerable to racist and destructive ideologies. Think about times when:

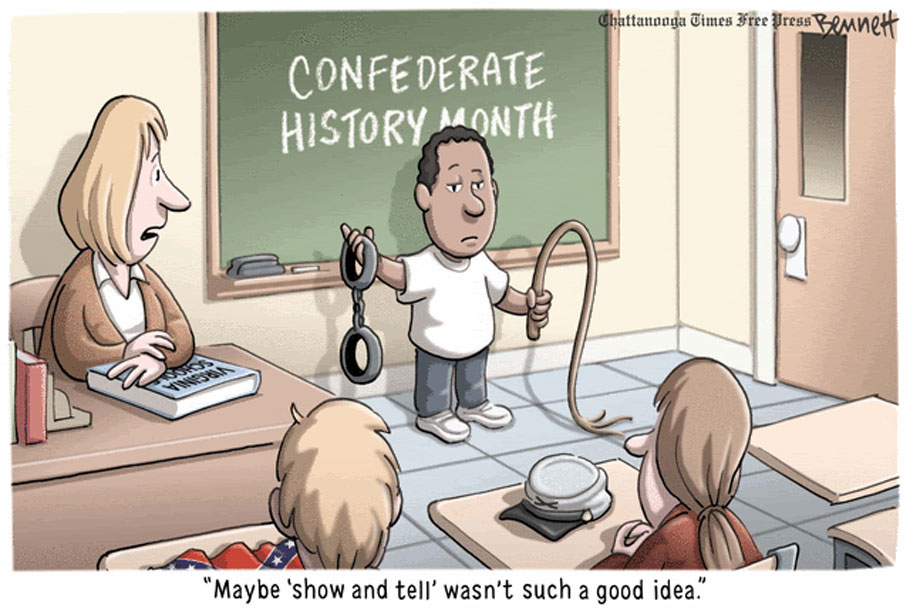

1. Faculty recklessly use the idea of “devil’s advocate.” We have heard many pundits talk about the value of both sides. This is premised on the notion that every intellectual idea has an equally rigorous opposite — the president of the United States used this line of reasoning to create a moral equivalency between protesters and counterprotesters in Charlottesville. I’ve heard faculty raise “other side” arguments in jest, or as a means of claiming political neutrality — often with little attention to accuracy. The pedagogical limitation of this approach is that it teaches students that any issue is subject to a point-counterpoint construction. “Some people believe that all people are created equal. Some other people believe in racial superiority,” says the professor. Yes, these are two ostensible sides of an issue, but the disparate impact and consequences of these ideas when they have been codified in the law require clarity and explanation.

2. Advisers and mentors roll their eyes when discussing inclusion. Our students are the most vigilant viewers; they watch us closely even when we believe they are not listening. If a student is in an adviser’s office, and a question about fulfilling the university’s diversity requirement is met with an eye roll and a sigh, the message that these courses are unworthy is made abundantly clear. When efforts to rethink canons and epistemologies are treated like a nuisance, students quickly understand them as lacking value.

3. We discount students’ voices. When our activist students ask for a more-inclusive curriculum and we immediately cite the bureaucratic nature of institutions (“It takes too long to approve new courses,” or “We won’t get the numbers”) instead of asking why the changes are important to them, we squander an opportunity to listen to our students and to consider their motivations and passion for learning.

4. We fail to acknowledge that the world affects students. Since 2014 I have helped faculty across the country find strategies to discuss national tragedies — from the uprisings in Ferguson and Baltimore, to the terrorist attacks in Orlando, and now in Charlottesville — in their courses, regardless of the class topic. White nationalists celebrate the pain and suffering of marginalized communities. When educators fail to recognize these moments as significant, they lose the chance to model solidarity and concern across lines of difference.

5. We leave stereotypes about college unchallenged. The caricature of campuses as bastions of liberalism is fodder for long-form journalism, movies, and anecdotes among colleagues, and white nationalists often draw on it to paint themselves as victims. Faculty and administrators who don’t know their student demographics and who have not kept abreast of the weakening of affirmative action over the past two decades cannot be trusted to offer thoughtful decisions or analyses on how far our institutions still have to go in delivering equity.

6. We fall into the trap of nostalgia. Those of us who have been on the job for a while and talk about a simpler time — such as when women were not admitted to our colleges or when the responsibility of ensuring parity was not before us — give our students a sense that we want to make universities great again by making them less democratic and socially responsible. When we express negative attitudes about accommodating students who fast during Ramadan, or we bemoan the requirements of the Americans With Disabilities Act, or we care more about statues and building names than about ensuring justice, then we cannot be surprised by the pedigree of those we fear.

These examples come from my past decade of living a life centered around the university and its students; I offer them without castigation. Rather, I ask that we no longer blame ignorance for where we are, and instead we depend on the impulse that brought us to teaching and research — the belief in inquiry, revision, and tenacity to come closer to enduring solutions. The stakes are far too high, and the lives of our students far too precious, to avoid a moral accounting of who we are in the classroom.

Marcia Chatelain is an associate professor of history and African-American studies at Georgetown University.