By Kai Wright,

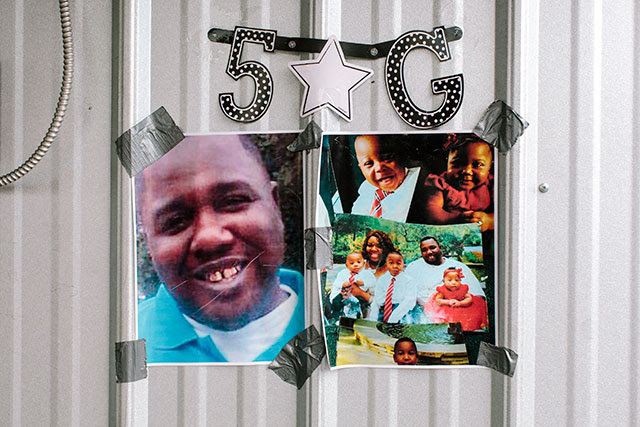

Photos of Alton Sterling outside the Triple S Food Mart, where he was shot and killed by police early Tuesday, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 6, 2016. The Justice Department opened a civil rights investigation Wednesday into the fatal shooting of Sterling, a Black man, by the Baton Rouge police that was captured on video. (William Widmer / The New York Times)

Photos of Alton Sterling outside the Triple S Food Mart, where he was shot and killed by police early Tuesday, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 6, 2016. The Justice Department opened a civil rights investigation Wednesday into the fatal shooting of Sterling, a Black man, by the Baton Rouge police that was captured on video. (William Widmer / The New York Times)

Alton Sterling and Philando Castile are dead, joining a long roll call of black people killed by officials acting in the name of public safety. And so the nation now begins a process so familiar as to have become rote.

Many of us will want desperately to know more about these men’s lives, not merely their deaths. After each of the many executions we have collectively mourned, I have grasped for those kinds of details — some reminder that black lives do actually matter, to somebody. Alton Sterling seems like he was a nice guy. He clearly had a friend in Abdullah Muflahi, who owned the food mart where he sold CDs and DVDs in the parking lot. Sandra Sterling, the aunt who raised him, says he was gregarious, perhaps self-consciously so. He used his large frame as a punch line, maybe to put others at ease with his size. “He made everybody laugh because he was chubby,” she told Nola.com. His cousin Krystal says he was a “people person,” which is why he figured selling CDs on the street was a useful way around the fact that he couldn’t get work in the formal labor market, thanks to a conviction for having sex with a minor when he was a 19-year-old himself. His customers — neighbors, really — seemed to genuinely enjoy him; they called him “Big A.” And he was good at his work. As one woman told The Washington Post, “That’s the most legit bootleg man in Baton Rouge.”

Castile’s killing is still too fresh for details of his life to begin seeping into the public record. He seems to have had a remarkable girlfriend — someone so clear of mind that she was able to livestream the immediate aftermath of her boyfriend’s death at the hands of someone who is paid to protect her. Or maybe that was just trauma, how the hell would I know. But his uncle, Clarence Castile, tells the Minneapolis Star-Tribune that the 32-year-old had worked in a school cafeteria “cooking for the little kids” for 12 to 15 years. So he’d spent his whole adult life feeding people. He had a mother, a sister, a cousin; they’ve all sobbed as the cameras have rolled.

These are just a few snippets of the lives taken in the name of public safety. I cling to them.

Of course, the ritual of parsing the lives of the dead must also include a consideration of their criminality. It is tradition for news media to report any prior evidence of criminality when covering these cases. A banality of this particular evil is the assumption that people who encounter cops — for that matter, people who have criminal records — have done something, anything meaningfully wrong. We simply cannot hold the idea that someone selling CDs in a parking lot or driving a car with a busted taillight or walking down the middle of the street or peddling loosies on the sidewalk or playing with a toy in the park is enough infraction to end up dead within minutes of encountering a cop; that would undermine the whole premise of authorizing a force of public safety officers. The dead must have some modicum of criminality, present some reasonable threat to the public. So news reports must include Castile and Sterling’s records, supplied by the police agencies that killed them, as though anything in those records could possibly explain their deaths.

In this vein, the now rote ritual of black death will also include much debate about the guns. Both Sterling and Castile were armed. Sterling’s friend, the food-mart owner, says he was carrying a gun because he’d been threatened; others say it was a reasonable security precaution given his cash-based business. Castile’s girlfriend says he was licensed to carry his gun and that he told the officer as much. The details of these guns will be crucial to the debate over accountability for the officers, because the sole legal question is whether the officers reasonably felt themselves or others to be in immediate danger. The answer in court — if any case makes it that far — is very likely to be yes. The law discourages second-guessing officers’ split-second, potentially life-and-death decisions. So there will not likely be justice in Baton Rouge or St. Paul.

Nor will there likely be peace, because of a simple fact about law enforcement: There is too much of it, touching too many aspects of daily life, creating too many opportunities for it to inflict violence upon the public it is supposed to serve. This has always been true for black people, in one way or another. From the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act forward, public-safety officers have been empowered to harass black bodies in the defense of private capital and the pursuit of public revenue. As a result, no generation of black Americans has been spared the macabre tradition of drilling into its children tips for avoiding death at the hands of the state — not during slavery, not during the era of black codes that followed war, not during Jim Crow, not during the indiscriminate war on drugs, and not in the current era of cops functioning as tax collectors on the poor in decimated municipalities.

Debbie Nathan’s moving biography of Sandra Bland in our May 19 issue is a must-read for understanding how this modern version of the 220-year-old system functions to destroy black life. From Illinois to Texas, Bland was stalked by an overzealous police apparatus that hunted vulnerable residents who could be targeted with fines and fees, money that local governments desperately needed to fill the holes created by state and federal austerity — zealotry that begat zealotry that begat death.

From case to case the details have shifted, but a depressing through line for all of the people whose names have become hashtags over the past two years is the ho-hum way in which their last moments began. In each case, one can reasonably ask why the encounter involved armed, hyped-up cops at all. Which points to a more fundamental solution than those we most often discuss when we march through the grimly familiar stations of public mourning and debate that will accompany Sterling and Castile’s deaths.

Yes, cameras are a reasonable precaution, both those worn by cops and those that brave citizens wield. Absolutely, better training in the use of non-lethal force and awareness of implicit bias is a must. Surely creating systems to evaluate law enforcement officials based on the help they provide rather than the arrests they make would improve things. And no doubt prosecutors need to be reined in. But all of these things ease the symptoms rather than treat the disease. We need to start asking why we have so much law enforcement in the first place, and whether much of it is truly needed.

Law-enforcement agencies are among the largest and most powerful bureaucracies in most localities, and they are deeply enmeshed in our daily lives, particularly in communities of color. They are our first responders. They are in our schools. They are our immigration officials. For the most vulnerable among us, they are often what passes for social workers and mental-health-care providers. And they are armed. At some point, we must question whether all of this law enforcement is necessary, and whether public safety is best served by having much, much less of it.

Kai Wright is editorial director of Colorlines.com and an Alfred Knobler Fellow of The Nation Institute.