Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, has taken on some massive subjects in his latest book: race, and the way America sees itself.

Who We Be: The Colorization Of America follows the rise of the idea of multiculturalism — and the backlash that followed it — from the Civil Rights movement through to Obama’s election, the fight over the DREAM Act, and Trayvon Martin’s death.

The book explores how race has figured in American visual culture since the 60s, and the rhetorical imagery that’s driven American politics. “We can all agree that race is not a question of biology,” Chang writes. “Instead it is a question of culture and it begins as a visual problem, one of vision and visuality. Race happens in the gap between appearance and the perception of difference. It is about what we see and what we think we see and what we think about when we see. In that sense, it’s bigger than personal affinities, preferences, tastes and bonds.”

Chang sat down with HuffPost to talk about how the culture wars are still with us today, what it means that we’re headed toward becoming a “majority-minority” society in 2042, and why America still hasn’t had the kind of “national conversation about race” that it really needs. (This interview has been edited and condensed).

What does “colorization” mean?

“Colorization of America” is a way of talking about the demographic shifts that have happened in the last five decades, and the cultural shifts that come along with that.

The civil rights revolution put into place a lot of policies that took down the framework of legal segregation. So with the Civil Rights Act and The Voting Rights Act, you saw the mainstreaming into American life of people of color. And with the Immigration And Nationality Act you saw the end of racist quotas against people from non-European countries, immigrants of color.

In the 70s and the 80s, the culture begins to shift drastically because of those changes. And this is something that has really thrown parts of the Right into huge paroxysms of fear.

But I was interested in looking beyond that and getting into what were the ideas then that people, that artists in particular, started to put out in order to describe these shifts — and that sort of prophetically looked at what could happen if America was made more inclusive.

That’s what colorization is really about, and obviously the narrative is that the end point would be 2042, when the U.S. becomes a “majority-minority country.” So it’s not just looking backwards, but anticipating the questions that get raised as we look toward 2042.

How is it different from the “browning of America?”

There’s the numerical, demographic shifts that occur, but I’m interested in the kinds of cultural exchanges that happen and the art that gets created and the kinds of sparks that fly when you get all of these different people from different backgrounds together. So I was really interested in the multiculturalism movement in the 70s. There’s scenes that are happening in New York and LA and around the country, Chicago as well, but the Bay Area is really where they start putting a name to it.

You see folks coming out of the feminist movements and the third world liberation movements who are all starting to hang out together and think about things, and then you have Ishmael Reed kind of plucking this word down out of the ether, the multiculture.

It’s weird and not particularly groundbreaking to think about the multiculture now, but at the time it was radical because there was only one way that people could see America being, that there was American culture, there wasn’t American cultures with a plural, and that you had to assimilate into a WASP kind of ideal in order to realize the American dream. So there are all kinds of cultural, political implications that came out of that.

When people talk just about the browning of America, we’ve gotten comfortable with describing every new generation that’s arriving as being the most diverse generation yet. But it lacks the context of all of the shifts that have happened and the point that we’re at now where we’ve kind of achieved, to a certain extent, cultural desegregation in our popular culture, coupled with the fact that racial resegregation, the wealth gap, the income gap, the housing gap, the education gaps are all on the rise. We have a very complicated picture of what this so-called browning is that doesn’t really get to the nuts and bolts of what’s actually happening here.

I was hoping to do something that was broader, a set of narratives that would be broader and ask some of those questions.

Portrait of writer Ishmael Reed, photographed in California in 1995.

You approach the issue of race through visual culture and the metaphor of sight. What made you fix on that as your entry point?

You could argue that after the Civil Rights revolution, seeing becomes a much more important metaphor for the way we understand the world, and in that sense the visual — and certainly the explosion of the visual culture in the last 40, 50 years — that it would be kind of important to understand how we see race now. What do we see, what are we still blind to. So I think I knew implicitly that I was going to have to take a deep dive into the visual culture when I started writing the book.

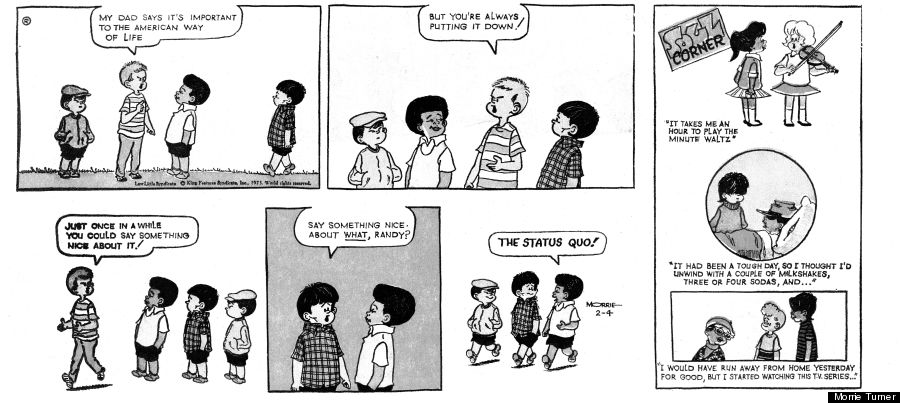

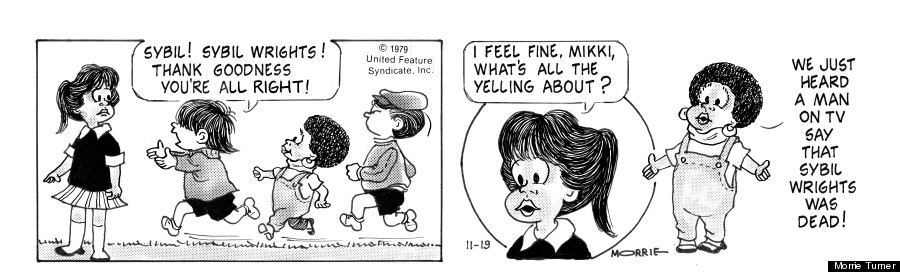

It started literally with a neighbor of mine, the late great Morrie Turner. What happens after the Civil Rights revolution is you’ve begun to dismantle the infrastructures of legal segregation, but people still have to imagine how they’re going to live together, and that’s where the artists kind of step in. So he has this comic strip called “Wee Pals” which is a multicultural, multiracial “Peanuts” that launches in early ’65, right at the peak of all of this activity around pushing through these pieces of legislation. And in it he has kids literally figuring out how to play together. And so it was by coincidence and wonderful accident that I ended up moving in a couple doors down from where Morrie spent all of his teen years that influenced him in creating this comic strip. And I ended up spending a lot of Tuesdays with Morrie, a lot of Wednesdays with Morrie, a lot of Thursdays and Fridays and Saturdays with Morrie, and that ended up becoming the first story that I dove into when I started actually researching and writing the book in earnest.

Based on your research, what do you think are some of the biggest things that go wrong when we talk about race?

An MTV/David Binder study that came out earlier this year looked at so-called millennials and whether they talk about race. It found that only 1 in 5 felt even remotely comfortable broaching a conversation with someone else about racial bias. 1 in 5. We’re not even talking about discrimination or inequality or inequity — we’re just talking about racial bias.

There’s a study that was done several years ago that found that, overwhelmingly, white parents don’t talk to their young children about race. I think a lot of that comes from good will. They look at how race has been used in the past and think “well if we don’t talk about it then we’ll be OK.”

And that’s been reinforced, of course, by conservative politics that have been trying to undo racial justice policies for decades — that say under the law we should not look at race at all. This has been used to undo policies meant to specifically address racial discrimination and racial inequity and cultural inequity. At the same time that that’s happening, parents of kids of color are much likelier to talk in their households about race. There’s a gap not just in wealth and income and housing and education, there’s a gap in how we even talk about it or don’t talk about it.

When you break it down it really comes to the question of, in each generation, do you remake the conditions that led to the racial injustice in the first place, or do you begin to have conversations that lead to larger conversations about how to address these types of issues once and for all? And the book, of course, just leaves more questions than answers on that, but certainly I feel like the kinds of conversations that we need to be having aren’t happening.

Even in the wake of Ferguson, there was a CBS-New York Times poll that asked two really interesting questions: one was, do you think the events in Ferguson raise the question of race and should lead us to having deeper conversations about this? And the other question was, do you think that the events in Ferguson have led to too much attention paid toward race? And what you find is a huge split. Blacks say overwhelmingly this raises issues we have to talk about. Let’s talk about race, folks! On the other hand, a plurality — not a majority, but a plurality of whites say, oh now we’re focusing too much attention on race. So one person’s invitation to a race conversation is another’s opportunity to leave the room. It shows these are moments of massive polarization.

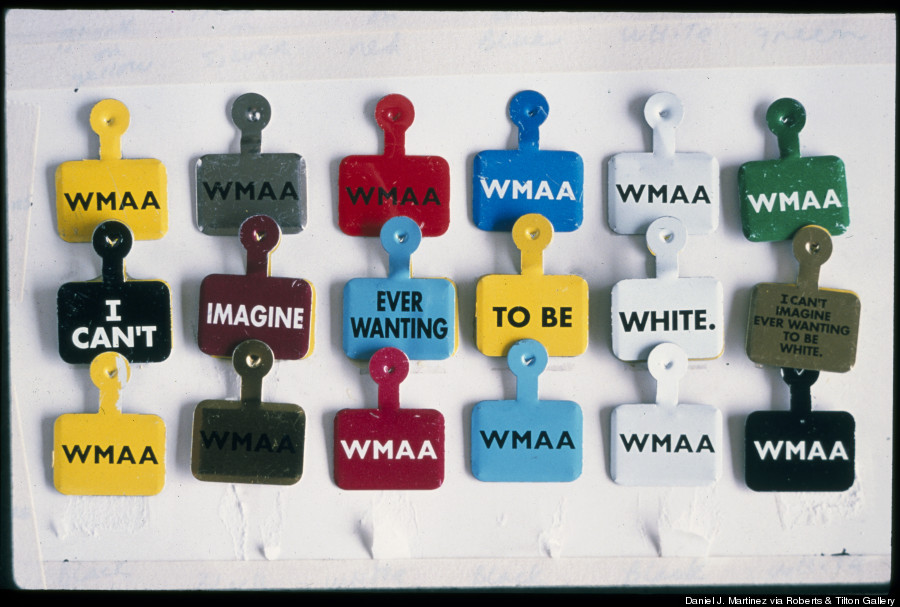

Museum tags from the 1993 Whitney Biennial designed by artist Daniel Joseph Martinez.

What would a productive national conversation about race look like?

I think it would get to the question of racial resegregation, despite the fact that we have cultural desegregation. It would lead to questions about why it is that our schools, our communities are becoming much more segregated, that we’re reaching levels of segregation in schools that we saw pre-Brown v. Board of Education. It would get to the question of not just income inequality and wealth inequality — this gap that’s yawned particularly over the last 3 decades — but would also deal with the racial wealth gap.

So we have to have those kinds of conversations, and these are the kinds of conversations that can’t be broached right now because people don’t necessarily even believe that these are issues.

I mean this kind of tongue-in-cheek, but: how can the “white community” deal with its tendency to see conversations about race as an assault?

I don’t know, you’d have to ask them! (laughs)

It’s hard because there’s this idea that equality for you means less shit for me, and that’s the success that the Right had in the 80s when they were rebuilding the Southern Strategy — I write about this in the book.

I think race comedy is actually really good, and maybe it’s the only weapon we actually have right now for progressives. Because it’s one of the few places where people can have these discussions and laugh about it. Now whether laughing about inequality — a joke about how a white person won’t get stopped and frisked but a man of color might — if I can laugh at that joke, does it mean I’ll be more likely to support the roll back of stop and frisk? I don’t know. I don’t know, but maybe that’s the start of a conversation about it.

There were several moments in the book where the Right co-opts the language and tactics of the Left. What’s the takeaway for you from seeing that dynamic play out over and over?

It’s part of the larger stop-and-go process of change in the U.S. In the 80s, the Right is co-opting the language of the Civil Rights movement. If we’d stayed where the Right was at, we’d still be using segregated bathrooms. But in the 80s, they make themselves out to be civil rights champions. By the end of the 90s, the Right is saying we’re all multiculturalists now — Nathan Glazer comes out with a book called We Are All Multiculturalists Now. George W. Bush appoints Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice and makes an attempt to “peel off” the Latino vote.

The boundaries of civility are reset, so they have to argue within that reset language. They have to use those terms to make themselves heard within the debate. And this is a point in which — and you see it in the art that’s happening now, in the discussions people are having within grassroots movements — there’s a need for new language now about how we’re going to define ourselves moving up to 2042 and beyond.

But all that reactionaries have to do is preserve the status quo, so they’re going to re-appropriate progressive language to preserve that and be heard. Those of us who are interested in change have to continually change the language and re-inscribe and re-instill new visions, new imaginations of what change can look like.

That’s partly why I was so interested in pursuing what it was that the artists were thinking, all the way through, because in a lot of ways these are folks who are working at the outer fringe of social acceptability and are able to see things that folks who are trying to work in policy and that kind of thing aren’t necessarily able to articulate.

How did you choose the title, and what did it mean?

I wish people would ask me that, actually, people haven’t really. It’s just sort of assumed, like, “oh yeah, ‘Who We Be,’ sure.” (laughs) I’m like, dude, this is DMX we’re talking about! And it’s straight up, anybody who knows me would know. A good friend of mine was like, “Oh yeah, Jeff’s the only dude who might be able to try to get away with making DMX sound intellectual.”

But in the heat of the culture wars, in the late 80s and early 90s, the big question was “Who are we?” Samuel Huntington wrote a book called “Who Are We?” in the mid 90s, this big, huge-ass polemic against immigration. And this question is related to the Pat Buchanan question: “What happened to the America we all grew up in?” Like, who are all these people, who are we now anyway??

For me, it just happened. Like, they don’t know who we be. Of course they don’t know who we be! They’re still asking “who are we?” And it just made perfect sense. So when I brought that up — I actually had the title before I had the book proposal — I said I want to do this book about mutliculturalism, it’ll be called “Who We Be.” My editor and my agent all go “Ohhhh that’s a good title!” (laughs)

And it’s interesting because it’s raised questions among linguists, particularly linguists of color. Like, why select this particular title? Is it an appropriation? And I explained to them the whole story I just explained to you, about how I wanted to do this book about multiculturalism and how it raised these questions of “who are we?” And I said, look, I completely understand how this could be read — there’s a certain politics of respectability that’s at work here.

But the ebonics debate was huge in the culture wars. If you look at that as a marking point for this fear of demographic and cultural change, then it’s a different way to understand what we’ve been through through the last three decades.

We approach these conversations on race, a lot of times, with a lack of history, with a kind of wipe-the-slate-clean kind of racial innocence. Because it’s an incredibly traumatic history, both for personal reasons for a lot of us as well as for national historical reasons. So in order to kind of get back to having the kind of conversations that matter, we have to be able to dive into that.

A visitor looks at a painting by Faith Ringgold named ‘Die: American people series #20’ during Contemporary Art Fair ‘Post-Picasso, contemporary reactions’ in Barcelona on March 7, 2014.

One of the challenges of multiculturalism seems to be conflicts between people of color, but that doesn’t really figure in Who We Be. Why was that?

It did in Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop — I think that was the heart of the book, actually. In the way that Morrie Turner was the starting point for this book, the starting point for Can’t Stop Won’t Stop was the section on the riots, in particular the debate that Ice Cube caused, with Death Certificate and Black Korea.

In this particular case, I was in a sense going back to my own days coming of age as an activist, as a student when these culture wars were raging during the late 80s and early 90s. And that was all about the legacies of the 60s, and Third Worldism, and the work of feminists of color and that kind of thing. It was idealistic, it was utopian. It was, by 1991, completely outmoded and by May 4 of 1992 in need of a sore rethinking. But I think the generation of us who came through the riots, a lot of us went into explicitly anti-racist but also coalitional type work, both organizing-wise and culturally.

And so it’s interesting at this particular point to kind of revisit that, because now that the discussion is around the question of 2042, when we’re all supposed to be minorities, the question becomes: if we’re all going to be minorities, how do you form a new majority? And I think that that’s the sort of central question of my students’ generation. They’re all 18 to 22 now, they’re going to be my age by the time 2042 rolls around. If they haven’t figured out even provisional answers to that question, they’re going to be in pretty tough shape.

There are so many things happening in the news this week that related to your book, I wanted to get your reaction to some of them.

Jesus Christ, I know!

So through the lens of Who We Be, what do you make of Annie Lennox choosing to cover “Strange Fruit?”

See, there’s an Annie Lennox fan in me that just wants to be like, “she just had a bad day and she was low on blood sugar and she didn’t know what she was saying.” But on the other hand — and I think this is the part that a lot of folks have pointed out — how could you not know what the history of this song is, and not honor it? Maybe there’s the British defense: “well I’m British, I don’t live in this kind of stuff day to day” or whatever. But come on, dude, look at the list of people you’ve worked with over the years. And to take it away from the context of lynching and racial terror — if she meant to do it, it was pretty fucking arrogant, let’s just say that.

Miami Heat players released a photograph of themselves wearing hoodies after Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager wearing a hooded sweat shirt, was shot to death on Feb. 26, 2012, in Sanford, Fla. by a neighborhood crime-watch volunteer.

The other thing that brought your book to mind was the report saying the great majority of artists who make a living off of their art are white.

I’d looked at a study as a setup for the chapter on Artists Space, [a nonprofit alternative gallery that opened in 1973], and that was the first time the census started to gather information on artists. If I recall correctly, there was no demographic breakdown back then, but I’d imagine the numbers were pretty much exactly the same back then. And it has to do, of course, with the economics of being an artist. It also has to do with the way that the Right has demonized the arts, straight up.

These surveys are people self-describing, so there’s the issue of self-describing as an artist as opposed to self-describing as somebody who is working in the service industry but who’s a beat maker or a painter or a photographer at night. So the Right began in the 80s to define artists as folks who were comfortably entitled and able to support themselves and make a living and all this kind of stuff, who then at the same time stick their fingers in the silent majority’s eyes with the kind of sexually explicit, horrifying, divisive art they were making. And they used that as a way to kind of create this frame around the artists so that they could defund the arts and erode and destroy cultural policy.

I really loved when you talked about “the opposite of a micro-aggression,” that kind of moment of recognition between two people — the “I see you” moment. I thought that could be a hopeful note to end on.

(Laughs) I think that that’s what we’re trying to achieve — we talk a lot about empathy, and of course empathy should lead to recognition. I’m recognizing your struggle, I’m recognizing who you are. I’m not being blind to who you are. And I think that that’s ultimately where we all want to get. That should be the product of whatever kind of conversation we’re trying to have.

There was an article on Medium this week about “the nod” — I remember in college I would hang out with a lot of black activists and I would notice that every time they passed another black student on campus they’d nod, and I’d go, “Oh, do you know them? Who’s that? I see them around all the time.” And they’d go, “I actually don’t know.” I’d ask “So why do you do that?” and they’d say “Well, you do. You just do it.” Or when someone is on stage and they’re performing and someone in the audience goes “I see you!” I’d always think about those kinds of cultural practices as being critical to solidarity-building.