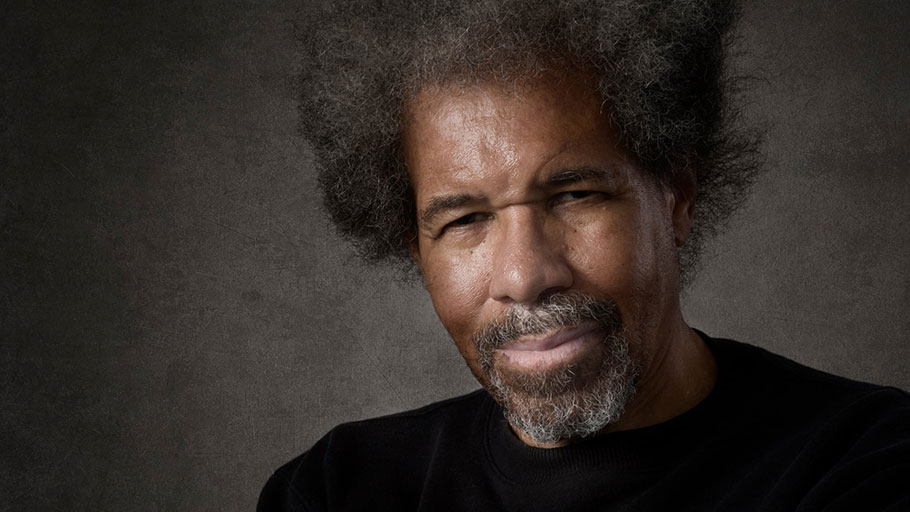

Albert Woodfox was released from prison in 2016 after more than four decades. Photograph: Peter Puna/Courtesy Grove Atlantic

The former Black Panther and member of the Angola 3 reflects on how he turned his cell from a place of confinement to a space for personal growth.

By Albert Woodfox, The Guardian —

My wrists were handcuffed to my waist by a leather strap. These restraints would become standard for me for decades to come. They walked me to a car and I got in. A captain next to me started elbowing me in my chest, face, and ribs. They drove me to a building just inside the front gate that housed the reception center and death row. Inside was a cellblock called closed cell restricted, or CCR: another name for solitary confinement. In the stairwell they beat me viciously. I couldn’t fight back or defend myself because of the restraints.

My body was badly bruised from being beaten but I was still able to move around the cell on my own. I walked to shake off the pain. The cell was 9ft long and 6ft wide. I could take four or five steps up and back the length of the cell.

In the late afternoon of 17 April 1972, the guards brought my friend Herman Wallace in and put him in the cell next to me. He had been beaten badly in the dungeon and in the stairwell of CCR. I couldn’t see him but we stood at our bars next to each other and talked. We talked about how we could let our families and party members know what happened to us. We both thought that the Black Panther party would save us and there would be a movement to free us. I thought there would be mass protests in the street. “The people will rise up and not let us be railroaded,” Herman said. That’s how naive we were.

We were locked down 23 hours a day. There was no outside exercise yard for CCR prisoners. There were prisoners in CCR who hadn’t been outside in years. We couldn’t make or receive phone calls. We weren’t allowed books, magazines, newspapers, or radios. There were no fans on the tier; there was no access to ice, no hot water in the sinks in our cells. There was no hot plate to heat water on the tier. Needless to say, we were not allowed educational, social, vocational, or religious programs; we weren’t allowed to do hobby crafts (leatherwork, painting, woodwork). Rats came up the shower drain at the end of the hall and would run down the tier. We threw things at them to keep them from coming into our cells. Mice came out at night. When the red ants invaded they were everywhere all at once, in clothes, sheets, mail, toiletries, food.

Our meals were put on the floor outside our cell doors. We stuck our hands through the bars to pull the trays underneath the door into our cell. Anytime we were taken off the tier, even if we were moving just outside the door to the bridge, we were forced to strip, bend over, and spread our buttocks for a “visual cavity search”, then after we got dressed we were put in full restraints.

If there is one word to describe the next years of my life it would be “defiance”. White inmate guards virtually ran CCR at the time. These inmate guards were brutal in their treatment of prisoners housed in CCR. They liked to threaten and taunt us, but they made sure to do it only if they were outside our cells or when we were in restraints. They weren’t stupid enough to put their hands on us if we weren’t restrained. They hated me and Herman because we didn’t put up with their racist comments. If they talked trash to us we talked trash back just as bad.

We talked down to them. We resisted orders. If they were jumping a prisoner we shook the bars and yelled. Any act of resistance ended the same way: four or five of them would come into the cell and jump us. It’s a hell of a feeling to stand when you know you’re going to be beaten; you know there will be pain but your moral principles won’t let you back down. I was always scared shitless. Sometimes my knees would shake and almost buckle. I forced myself to learn how not to give in to fear. That was one of my greatest achievements in those years. I didn’t let fear rule me. We were always outnumbered. I was scared, but I was mentally strong.

Gassing prisoners was the number one response by security to deal with any prisoner at Angola who demanded to be treated with dignity. In the 70s we were gassed so often every prisoner in CCR almost became immune to the teargas.

The most effective way of protesting was the hunger strike. If we didn’t eat for three days prison officials were required by law to notify the Louisiana department of public safety and corrections. Ranking officers didn’t want state officials called to the prison. They might find something wrong besides what the prisoners were protesting. Once we voted to go on a hunger strike to get toilet paper that wasn’t being passed out. Just the threat of a hunger strike, that time, got the tier guard to pass out the toilet paper. Our victories were few, but each victory made up for the losses before it. It was an adrenaline rush to win.

Herman, Robert King, and I had so many battles with the administration during the 70s that they run together in my mind now. Any one of our protests could have gone on for a few hours or a whole day, and there were some that lasted day and night.

There was a prisoner on D tier named Arthur Mitchell who had a lot of success filing lawsuits against the prison. For that reason, the guards didn’t fuck with him. I borrowed a dictionary of law terms from Arthur and started checking law books out of the prison library. I read case law, day and night, standing, sitting, or lying in my bunk. Some days I sat on the floor of my cell with four or five law books open around me.

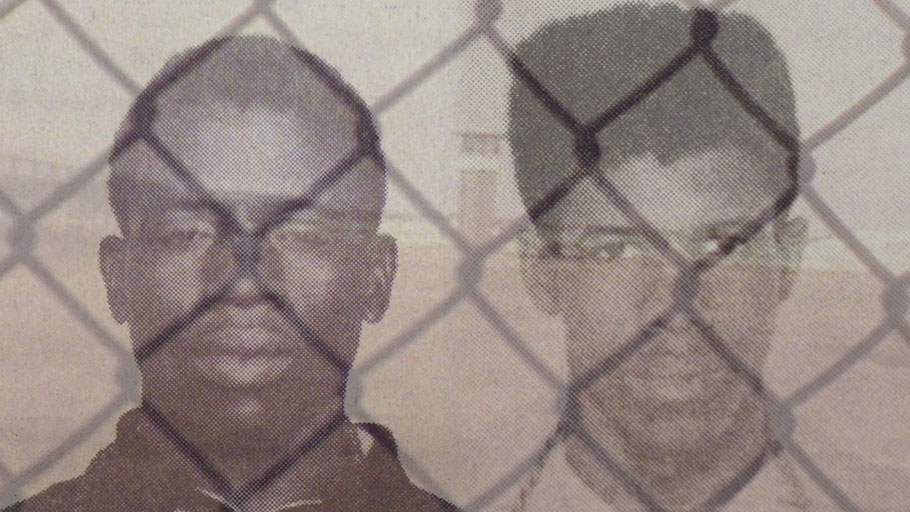

Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox in the early 1970s. Photograph: In the Land of the Free film still.

The first lawsuit I won, around 1974 or 1975, was against the department of corrections rule that didn’t allow prisoners to wear any items of clothing with brand names or logos.

Between filing grievances, going to court, and our constant protests on the tier to be treated humanely, we gradually gained privileges that had not been allowed in CCR before. Over time we were granted permission to have individual fans, radios, and books in our cells. We could subscribe to newspapers and magazines. In the mid-70s, we got screens on the windows that kept the mosquitoes out. Sometime in the late 70s, Herman, King, and I were actually allowed to share a record player.

My proudest achievement in all my years in solitary was teaching a man how to read. His name was Charles. We called him Goldy because his mouth was full of gold teeth. The first time I heard Goldy read a sentence out of a book I told him how proud I was of all he’d learned. He thanked me and I told him to thank himself. “Ninety-nine per cent of your success was because you really wanted to read,” I said. Within a year he was reading at a high school level. The world was now open to him.

Solitary confinement is used as a punishment for the specific purpose of breaking a prisoner. Nothing relieved the pressure of being locked in a cell 23 hours a day. In 1982, after 10 years, I still had to fight an unconscious urge to get up, open the door, and walk out.

The only way you can survive in these cells is by adapting to the painfulness. The pressure of the cell changed most men. I’d see men who’d lived for years with high moral principles and values suddenly become destructive, chaotic.

You look for the good. This can set you up for disappointment. Once I did some legal work for a prisoner that reduced his sentence to “time served”. He was going to be released from prison because of the work I did for him. The day after he found out he came to the door of my cell and threw human waste at me. He was pissed off because I was watching the news and I wouldn’t let him change the TV channel to a different program. You can’t hold on to those experiences or you become bitter. Every day you start over. You look for the humanity in each individual.

I made my bed every morning. I cleaned the cell. I had my own cleanup rag I used to wipe down the walls. When they passed out a broom and mop I swept and mopped the floor of my cell. I worked out at least an hour every morning in my cell.

By the time I was 40 I saw how I had transformed my cell, which was supposed to be a confined space of destruction and punishment, into something positive. I used that space to educate myself, I used that space to build strong moral character, I used that space to develop principles and a code of conduct, I used that space for everything other than what my captors intended it to be.

In my forties, I saw how I’d developed a moral compass that was unbreakable, a strong sense of what was right or wrong, even when other people didn’t feel it. I saw it. I felt it. I tasted it. If something didn’t feel right, then no threat, no amount of pressure could make me do it. I knew that my life was the result of a conscious choice I made every minute of the day. A choice to make myself better. A choice to make things better for others. I made a choice not to break. I made a choice to change my environment. I knew I had not only survived 15 years of solitary confinement, I’d honored my commitment to the Black Panther party. I helped other prisoners understand they had value as human beings, that they were worth something.

Malcolm X wrote, “Every defeat, every heartbreak, every loss, contains its own seed, its own lesson on how to improve your performance the next time.” Malcolm gave me direction. He gave me vision. The civil rights leader Whitney Young said of being black: “Look at me, I’m here. I have dignity. I have pride. I have roots. I insist, I demand that I participate in those decisions that affect my life and the lives of my children. It means that I am somebody.” There wasn’t one saying that carried me for all my years in solitary confinement, there were one thousand, ten thousand. I pored over the books that spoke to me. They comforted me.

The closest I ever came to breaking in prison was after my mom died, on 27 December 1994. I used to tell myself, “If you can breathe you can get through anything.” When my mom died my breath was snatched from me. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t catch my breath. I always thought if I lived long enough, I’d win. But now she was gone and I could never have her in my life again, no matter how long I lived. I wondered if, without my mom, I would ever be able to breathe again.

A year after my mom passed away I was sitting on my bunk trying to figure something out when I heard my mom’s voice in my head. It was like her voice echoed through the years to speak to me.

***

On my release, on 19 February 2016, my brother Michael took me home and I lived with him and his wife and son in their house for almost a year. I got medical care that I needed. In my mind, heart, soul, and spirit I always felt free, so my attitudes and thoughts didn’t change much after I was released. But to be in my physical body in the physical world again was like being newly born. I had to learn to use my hands in new ways – for seat belts, for cellphones, to close doors behind me, to push buttons in an elevator, to drive. I had to relearn how to walk down stairs, how to walk without leg irons, how to sit without being shackled.

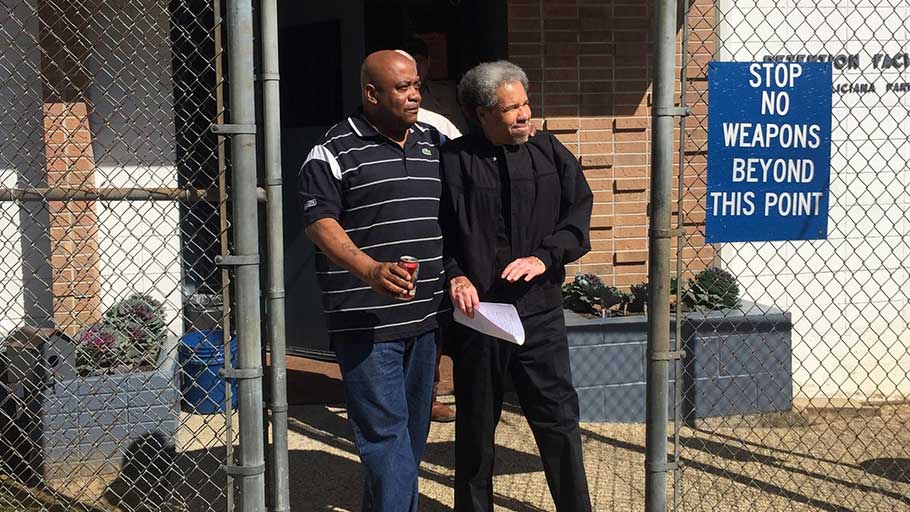

Albert Woodfox accompanied by his brother Michael Mable on his release from prison. Photograph: BILLY SOTHERN/EPA

It took about a year for my body to relax from the positions I had gotten used to holding while being restrained. I allowed myself to eat when I was hungry. Gradually, over two years, I let go of the grip I held against feeling pleasure, and of the unconscious fear that I would lose everything I loved.

Michael told me I needed to make new memories, and I did. I’d always dreamed of going to Yosemite national park after seeing a National Geographic special about it years before in CCR. At the invitation of old friends and former Panthers Gail Shaw and BJ, I flew to Sacramento. Scott Fleming came up from Oakland to meet us and we drove to Yosemite together. We hiked to the falls I wanted to see, and we stayed in the park overnight.

A great joy has been getting to know my daughter and her children. My great-grandchildren are my hope. The innocence, intelligence, and happiness in their eyes give me strength. I want to keep going for them, keep speaking out, keep fighting. I hope to leave them a better world than the one I had. I hope they can find the spirit of my mom, their great-great-grandmother, when they need her, as I did.

I bought a house. I’m still a news junkie and usually have news on the TV. I can still only sleep a few hours at a time. I am often wide awake around 3am, when I used to get some “quiet time” in prison. Many people ask me if I ever wake up and think I’m still in prison. I always know where I am when I wake up. But sometimes I walk into a room in my house and I don’t know why, and then I walk into all the rooms for I don’t know what reason. I still get claustrophobic attacks. Now I have more space to walk them off. For peace of mind, I mop the floors in my home.