You can’t pray for the workers in Baltimore and also be against their dream to come to America.

By Petula Dvorak, The Washington Post —

Does America need a more searing visual image than eight men working for their piece of the America dream — filling potholes on a terrifying bridge in 1 a.m. darkness — to understand that our nation was built by immigrants, runs on immigrant labor and needs immigrants?

Six of those men, migrants from Mexico and Central America, pierced our consciousness this week because they plunged to their deaths in the Patapsco River when a Singapore-flagged cargo ship razed Baltimore’s mighty Francis Scott Key Bridge.

Social media was a lovefest of thoughts and prayers for those men.

“Pray for the souls of those construction workers!”

“Please pray for the missing construction workers and their families.”

A song is performed during a Catholic Mass at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in Baltimore for those impacted by the collapse of the Key Bridge. (André Chung for The Washington Post)

But when it comes to the reality of who these workers were, how they got here and why they came, more than a quarter of us lose our minds — and our hearts.

A disconcerting 61 percent of Americans see illegal immigration as a “very serious” problem, according a poll by Monmouth University last month. More than half of the poll’s respondents said they support building a border wall.

Must be an election year.

The fact is, the kind of men who were on that bridge are doing this every day across the nation — the work that needs to be done. Dangerous work.

While foreign-born “Hispanic or Latino” immigrants made up 8.2 percent of the workforce in 2021, they accounted for 14 percent of work-related deaths that year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Fatal injuries to this group were more prevalent in the field of construction, with falls, slips and trips being the most frequent event leading to death,” according to a report by the agency.

Our culture honors — with big gestures — the dangers that law enforcement officers face in the line of duty every day. But their work is the 22nd most dangerous profession in America, according to a different analysis by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Policing is far behind the occupations of landscaping, roofing, farming, garbage collecting, constructing, and maintaining the nation’s highways — all jobs widely filled by immigrants.

Construction workers in Cherry Hill, N.J., with the Philadelphia skyline in the distance. (Michelle Gustafson for The Washington Post )

This has largely been the story of America. While our nation’s immigrants are senators, doctors, lawyers and professors, many more start their American lives in jobs that literally build the nation. From the Transcontinental Railroad to the New York skyline and the Golden Gate Bridge, a world of immigrants arrived and built upon the forced labor of the enslaved.

“If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost,” President Ronald Reagan said in a 1989 speech.

And yet, we did close those doors many times, then cringed at what we saw in the rearview mirror:

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (restricting Chinese immigrants). California’s Alien Land Laws of 1913 (targeting Japanese immigrants). The Barred Zone Act of 1917 (barring all migrants from a zone stretching from the Middle East to Southeast Asia and including a literacy test designed to foil immigrants from Europe). The Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929 (targeting Mexican migrants). The Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 (this one’s for Filipino immigrants.)

I can keep going.

But each time, the restrictions — born of fearmongering and jingoistic propaganda — eventually fell. And not always because we reset our moral compass to the noble principles of Emma Lazarus on the Statue of Liberty or speeches by Reagan, but because America needs immigrants.

It’s what makes the most recent surge of anti-immigration sentiment so face-palming.

We are in the middle of a stunning worker shortage.

Gasped at your grocery bill?

Surprised by the reduced hours at your local businesses?

Having a hard time finding a health-care provider?

“We hear every day from our member companies — of every size and industry, across nearly every state — that they’re facing unprecedented challenges trying to find enough workers to fill open jobs,” according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

The pandemic and boomer retirement has something to do with this, but the most glaring factor is a decline in migration that’s lasted nearly a decade, the chamber folks said.

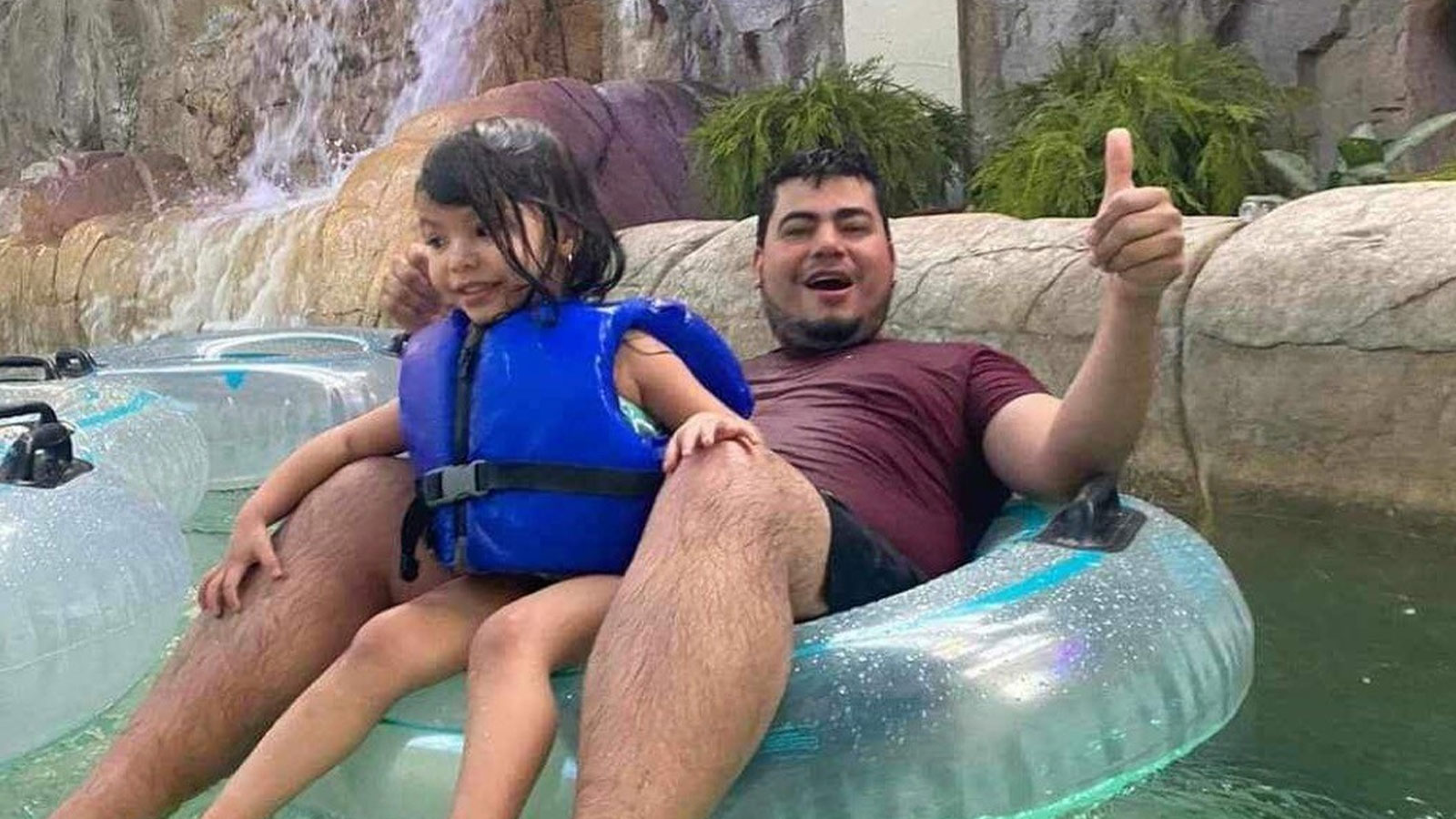

We simply haven’t had enough people like Maynor Yassir Suazo Sandoval, 38, one of the bridge workers presumed dead.

He was the youngest of eight kids born in the mountains of Honduras before coming to Maryland to work in the construction business 18 years ago.

Maynor Yassir Suazo Sandoval, a worker presumed dead after the collapse of the Key Bridge, with his daughter, Alexa. Suazo, a native of Honduras, came to the United States nearly two decades ago. (Family photo)

He married and had kids, loved soccer and called his family in Honduras for every event, his network back in Honduras told The Washington Post.

He eventually built his own package delivery company, adding to the $19.5 billion in taxes that immigrants in the Washington region contributed to the economy. When his business faltered during the pandemic, he went back into construction, and onto that bridge.

“He always told us that you had to triple your effort to get ahead,” his brother said. “He said it didn’t matter what time or where the job was, you had to be where the work was.”

Petula is a columnist for The Post’s local team who writes about homeless shelters, gun control, high heels, high school choirs, the politics of parenting, jails, abortion clinics, mayors, modern families, strip clubs and gas prices, among other things. Before coming to The Post, she covered social issues, crime and courts.

Source: The Washington Post

Featured image: Ship personnel aboard the cargo ship Dali, entangled in debris after crashing into the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore. (Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)