In a new Hulu docuseries based on a 2021 Wired article, a chorus of cultural luminaries discuss the jokes, memes, and transformative social movements generated by Black users on the popular social-media site.

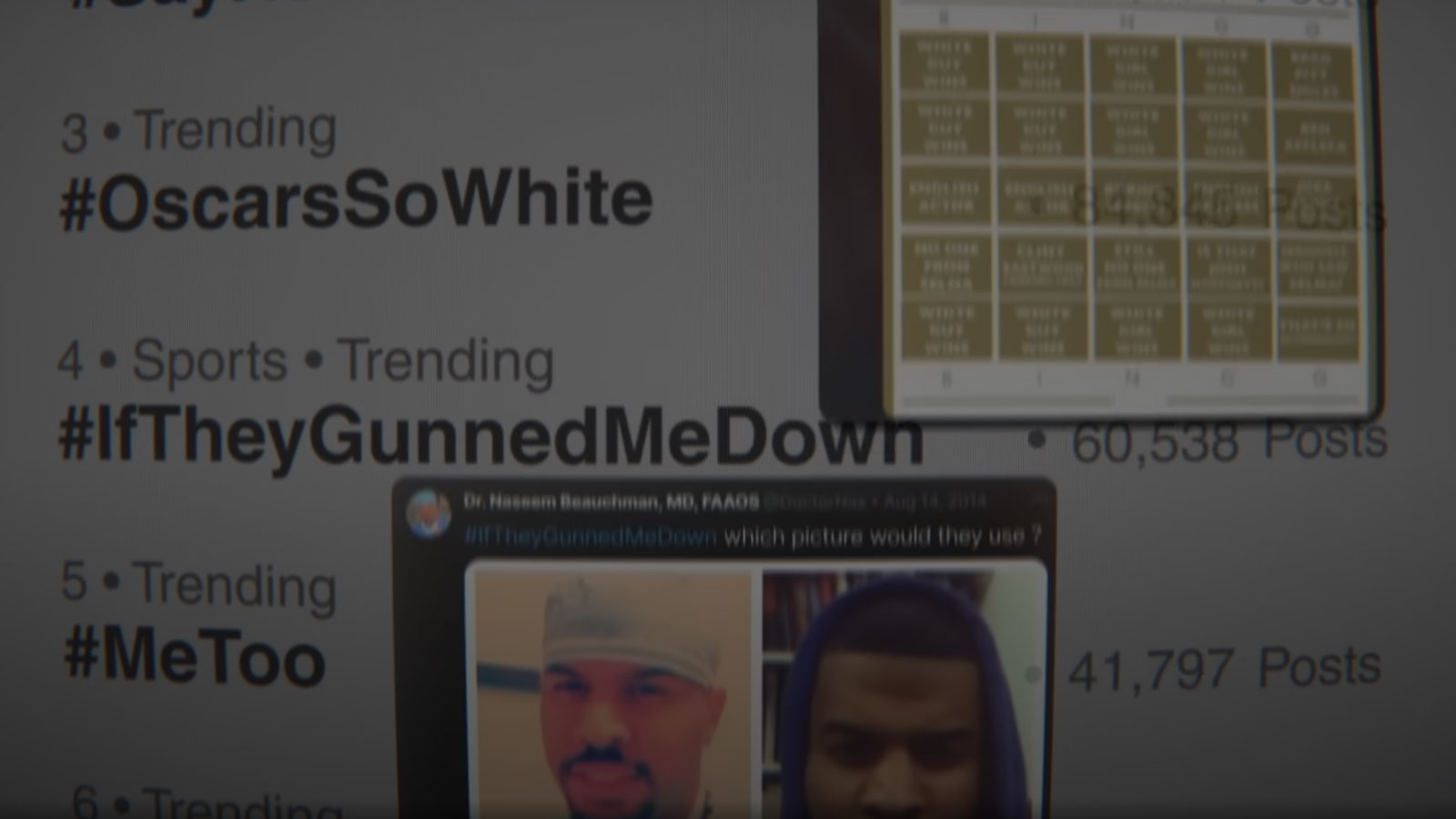

From the death of Osama bin Laden (as announced by Dwayne Johnson) to the rise of Donald Trump, from #TheDress to the Oscars slap, it’s impossible to imagine the last twenty or so years of global cultural history without Twitter, the microblogging platform that no one has ever referred to as “X.” And over the past two decades, no subsection of the app’s vast user base has produced more enduring memes, more culture-shifting social-justice hashtags, and more pure comedy than the cohort known as Black Twitter, which turned Crying Jordan into a legend and #BlackLivesMatter into a movement.

As journalist Jason Parham wrote in the introduction to an oral history of Black Twitter published in Wired in 2021, “It is both news and analysis, call and response, judge and jury—a comedy showcase, therapy session, and family cookout all in one.” Parham’s story was published years before Elon Musk showed up to Twitter headquarters with a sink, casting doubt on the platform’s future; it was the possibility of Twitter ceasing to exist that convinced Prentice Penny to sign on as director of Black Twitter: A People’s History, a three-part Hulu docuseries adapted from Parham’s story.

“If Elon was to turn the platform off today,” Penny said, “who’s going to tell my grandkids about what we did here?”

During his five-season run as the showrunner of HBO’s Insecure, Penny felt the power of Black Twitter firsthand. Each episode became an event, as thousands of fans live-tweeted their reactions and turned scenes into viral GIFs. He’d also watched state and local governments ban books and revise school narratives around actual historical events like slavery, and didn’t want to see the same thing happen to the historical record of Black people’s contributions to one of the most influential social-media platforms of all time.

He acknowledges that when the project was announced, it was met with skepticism, particularly on Black Twitter itself. “I was seeing tweets in the beginning like, ‘Who’s making this? We were all there,’” Penny recalls. But as he notes, not everybody actually was there: “My mom wasn’t on Twitter. My wife wasn’t on Twitter like that. There’s a lot of Black people that are not on Twitter and there’s a lot of Black people who are going to come from behind us who will never be on it.”

To preserve that legacy, A People’s History of Black Twitter assembles a who’s who of Twitter users and Twitter legends, including #OscarsSoWhite creator April Reign, sports journalist Jemele Hill, best selling author Roxane Gay, transgender rights activist Raquel Willis, former TMZ cohost Van Lathan, TV personality Brandon “Jinx” Jenkins, comedian Kid Fury, and Emmy-winning producer W. Kamau Bell, among many others, all weighing in on a phenomenon that’s had an indelible impact on 21st-century culture.

“It’s a tech doc,” Penny says. “It’s a political doc. It’s a culture doc. It’s a doc about race. It’s a doc about so many things.”

GQ: How would you define Black Twitter for someone who has no clue what that term means?

PRENTICE PENNY: I would describe it as a digital public space where Black culture dominates conversations. It’s so amorphous, and is obviously so many things.

Yeah. It is quite difficult to define. Whenever I’m talking to someone who’s white, for example, they’re always like, “How can I get on Black Twitter?” I’m like, “It’s not a Reddit forum that you can join. You are just there or not.”

You just have to know what subjects are going to matter. You got to know what hashtags to look for. People have asked, “What’s the difference between Twitter and Facebook and why do you think it happened there?” The one thing about Facebook is how it’s made up of your family members or people you went to high school with, at least initially. You had to go to Harvard or you had to go to an Ivy League.

Whereas Twitter was like, you got to be willing to be uncomfortable. You’re going to be around strangers, so you have to be willing to go into neighborhoods and areas that aren’t going to be super familiar. I don’t think that’s a typical thing most mainstream Americans are accustomed to doing in their normal life.

Who were you the most excited to have in this doc?

There were so many people. Jinx was someone I was super excited to talk to. Then there were people like Meredith Clark who I had heard of always says smart things, and then when you meet them you’re like, “You’re even smarter in person than I already thought you were.”

I got to know April Reign more, who created #OscarsSoWhite, but then there were people like Kalin, who is Squint Bae, who I was like, “I’ve used your GIF and meme so many times and now I get to talk to you.” People like that, or people like CaShawn Thompson where you’re like, “I’ve heard my wife tell my daughter ‘Black Girl Magic’ 50 million times.” To meet the first woman that tweeted that was like, “Wow. It came from somewhere—and it came from you.”

What do you foresee as the future of Black digital spaces if Twitter were to crumble? Do you see people trying to replicate the spirit of Black Twitter somewhere else?

I don’t think you can replicate it because so many things were converging factors. The economy converging with the rise of Obama and our naivete about social media at the time. We were starting to consume so much social media. Now we’re like, “Whoa. Whoa. Whoa. A lot of social media’s not that good.”

I don’t think you could ever replicate it. It’s like, I don’t know, how do you replicate Martin Luther King meeting Rosa Parks? Those things just hit at the right time, at the right moment. I don’t think it’s TikTok. I think things are happening there, but I don’t think it’s going to be like that. Black people are always good at finding community.

When I see my kids, they just have a Black Twitter energy even though they’ve never been on Black Twitter because they’ve just grown up in a world where Black Twitter just exists. They’re hearing things like “Black Lives Matter,” hearing about “Black girl magic” and “Black boy joy.” Whereas I didn’t see that growing up. I grew up a child of the ’80s. Assimilation was the thing. This generation is not about that.

What would you define as a Black Twitter energy?

I would define a Black Twitter energy as anything that is unapologetically Black. I’m going to wear my hair natural if I want to and if a Karen is talking crazy to me, I’m going to call that out. You know what I mean? Where it’s like, “I’m not just taking it, swallowing it. I’m just moving how I’m moving. You can choose to deal with that or not, but that’s more going to be a you issue, not a me issue.” To me, it’s just being unapologetically our culture without worrying about anything else behind it.

When you were talking to these creators, did you get the sense that any of them had been able to capitalize on their memes and slogans in a way that improved their lives?

No, not initially because I don’t think anybody was posting from that standpoint. Social media, at that time, was the Wild West. I would equate it to how a lot of the early rappers that started hip-hop didn’t benefit financially, because of the record labels taking advantage of them, or them not knowing where this was going to go. But when I think about rappers now, I’m like, “Saweetie has a McDonald’s meal.” Travis Scott‘s partnered with Nike. We’re just smarter because of the things that, sadly, didn’t take place before.

But I do think about somebody like Zola who was able to capitalize on that. Reesa Teesa is clearly going to be making something. Now we’re just savvier. In the super early days, I don’t think anybody was thinking this was going to be anything but just having fun and posting stuff.

Do you feel like studio executives or other showrunners are looking at Black Twitter for threads to turn into movies or shows? Do they also have Black Twitter in mind when creating and greenlighting shows?

I’ve never had those conversations with my showrunner friends, especially Black ones. I think trying to guess what Black Twitter will like or respond to is a fool’s errand, and you will be clowned immediately if you’re like, “They’re going to mess with…”

My philosophy is just do whatever you want to do and you’ll figure out how they respond to it. You know what I mean? I’ve never had conversations, like, “This viral thread will be a hit.” By the time it gets to showrunners or people like that, it’s already a thing that social media is talking about. Now we’re just figuring out how to creatively turn this into something else. Is it a limited series? Is it a ongoing series? Is it a movie?

Do you have an all-time favorite Black Twitter moment?

Zola is one of my favorite moments. It was like we were having a real watch party about a real person, which is what we had done for shows like Scandal. I just remember refreshing it. I’ve been writing a long time and I could never write a twist like that. It was just like, “This is crazy.” We got to participate in this as a culture. Then to watch what it became, I was just like, “Only Black culture or Black Twitter could do something like this.”

The Alabama brawl was one of my favorite recent ones. Also when the Queen died, Black Twitter had zero chill. Black Twitter was teaming up with Irish Twitter, diaspora Twitter, and diaspora Black Twitter. But even seeing the way Black Twitter participated on the platform during the pandemic on Verzuz. They were commenting on Teddy Riley’s audio not working and just the jokes and the bits. I remember the Xscape/SWV one being like, “Xscape up here sounding a little rusty.”

I don’t know how to equate a space where Black people get to do that. The closest thing is Essence Fest, where we’re all together for the same thing. There’s no issues. We’re just together celebrating our culture.

Source: GQ