By Dewayne Wickham

In the end, it was a diseased body and the infirmities of age that drained the life from Fidel Castro, not one of the many assassination plots hatched by the CIA or his enemies among the gaggle of aging Cuban expatriates based in Miami’s Little Havana.

For nearly half a century Fidel Castro Ruiz held a tight grip on the reigns of power in Cuba, an island nation 90 miles off the tip of Florida. But despite its closeness to the United States, Cuba — and its bearded leader — charted a wide berth away from its North American neighbor.

For much of Castro’s time in power, Cuba was an ally of the Soviet Union, the communist, Cold War superpower that the longtime Cuban leader also outlived. But more than anything else Castro was a socialist revolutionary who, despite his middle class upbringing and private school education, connected with the masses of Cubans when he launched the revolution that brought him to power on New Year’s Day of 1959.

Forty years later, I was one of two journalists who accompanied six members of the Congressional Black Caucus on a fact-finding mission to Cuba that resulted in a six-hour dinner meeting with Castro on Feb. 19, 1999.

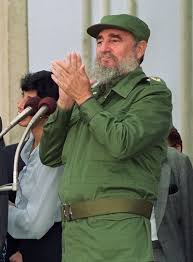

With a pig roasting on an open pit just behind where he was seated, Castro, dressed in military fatigues with a gun strapped to his waist, looked very much like a banana republic dictator that day. But he was not cut from the same cloth that produced his predecessor, Fulgencio Batista; or that gave rise to the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo or Haiti’s Jean-Claude Duvalier.

They were U.S.-backed, anti-communist dictators. Castro was a leftist who challenged American hegemony in Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America. He openly courted the embrace of the Soviet Union; an offense that forever stained his relationship with the United States — even now, 25 years after the Soviet Union’s collapse.

His critics will blame Castro for dragging the world to the brink of nuclear war in 1962 after the United States discovered that he’d allowed the Soviet Union to place nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba. They will accuse him of running a police state with massive human rights abuses.

But during that 1999 dinner meeting, Castro told the black caucus members that he would offer no apologies for jailing people his government believe were aiding and abetting American efforts to topple his government. And there was no mea culpa for his role in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In truth, Castro spent much of his life — figuratively, at least — in the ideological bunker that he and his fellow revolutionaries took to after a failed U.S.-sponsored invasion of Cuba in 1961. While his troops quickly defeated the 1,400-member invasion force that landed at the Bay of Pigs, an inlet on Cuba’s southwestern coast, he spent the rest of his life looking across the Florida Straits for the next wave of invaders.

While it never came, Castro had good reason to be paranoid. Under a succession of American presidents the United States pursued scores of attempts to assassinate him, according to a former head of Cuba intelligence.

In the end, not only did Castro survive those plots, he burnished his image with many members of the United Nations who routinely voted over the past 25 years to end the U.S. economic embargo of Cuba. Last month 191 nations backed the nonbinding resolution. The United States and Israel abstained.

POLICING THE USA: A look at race, justice, media

The overwhelming support for this nonbinding resolution can be traced to Cuba’s dispatches of thousands of doctors to countries in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean to treat people in places where there is a scarcity of medical professionals. This so-called medical diplomacy, which was launched by Castro, has won Cuba a lot of friends around the world.

So too did Castro’s decision to dispatch tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers to southern Africa during the Cold War. Those troops played a key role in helping socialist governments come to power in Angola, Namibia and Ethiopia.

“He was a revolutionary at a time when African countries were throwing off the yoke of colonialism,” Melvin Foote, president of the U.S. based Constituency on Africa told me shortly after news of Castro death was made public.

“I’ve talked to a lot of presidents in Africa and while he (Castro) was not a friend of the U.S., he was widely seen as a friend to many African governments,” Foote said.

Given all of this, it is hard to imagine that there could have been a better ending to the tumultuous life of Fidel Castro, who died Friday of natural causes at age 90.

DeWayne Wickham is dean of Morgan State University’s School of Global Journalism and Communication.