All along the way, his eye is trained on moments of calm, locating an inherent grace, style, and sublime beauty in the Black everyday.

By Jordan Coley, The New Yorker —

Hanging in the fourth-floor study of the renowned photojournalist Chester Higgins’s Fort Greene brownstone is a bunch of large dead leaves, fastened to a line in front of a well-stocked bookcase. Higgins grew the leaves in his window boxes, he told me, and he’s been making photographs of them for some time now. It’s a way, he said, to examine how “the spirit” manifests in all natural things.

“Ocean Spray, Accra, Ghana,” 1973. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Traditional Dancer, Ghana,” 1973. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Desert Wind Attire, Mopti, Mali,” 1993. Photograph by Chester Higgins

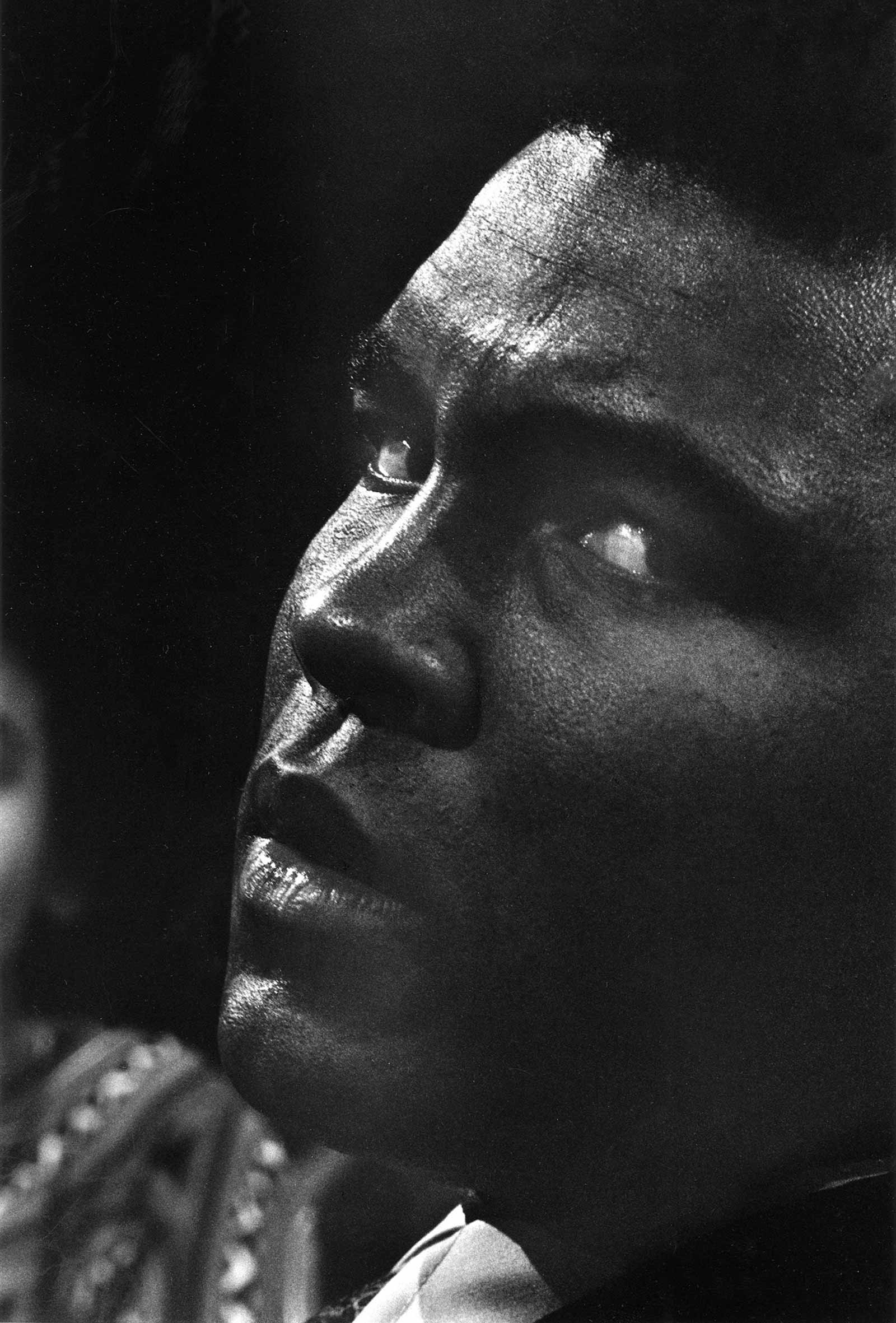

The spirit—a transportive, deeply human, ineffable quality that graces all memorable art work—is what the seventy-four-year-old photographer has spent his entire career trying to capture in pictures. He glimpses it in the cracking veins of old foliage, but also among the countless people he’s photographed across the decades: Muhammad Ali casting a mischievous sideward glance on the set of a television show; Aretha Franklin performing at the Apollo, her brow embroidered with sweat; a young Black boy, revelling in the spray of a fire hydrant.

“Aretha Franklin at the Apollo, Harlem, New York,” 1971. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Muhammad Ali, New York City,” 1972. Photograph by Chester Higgins

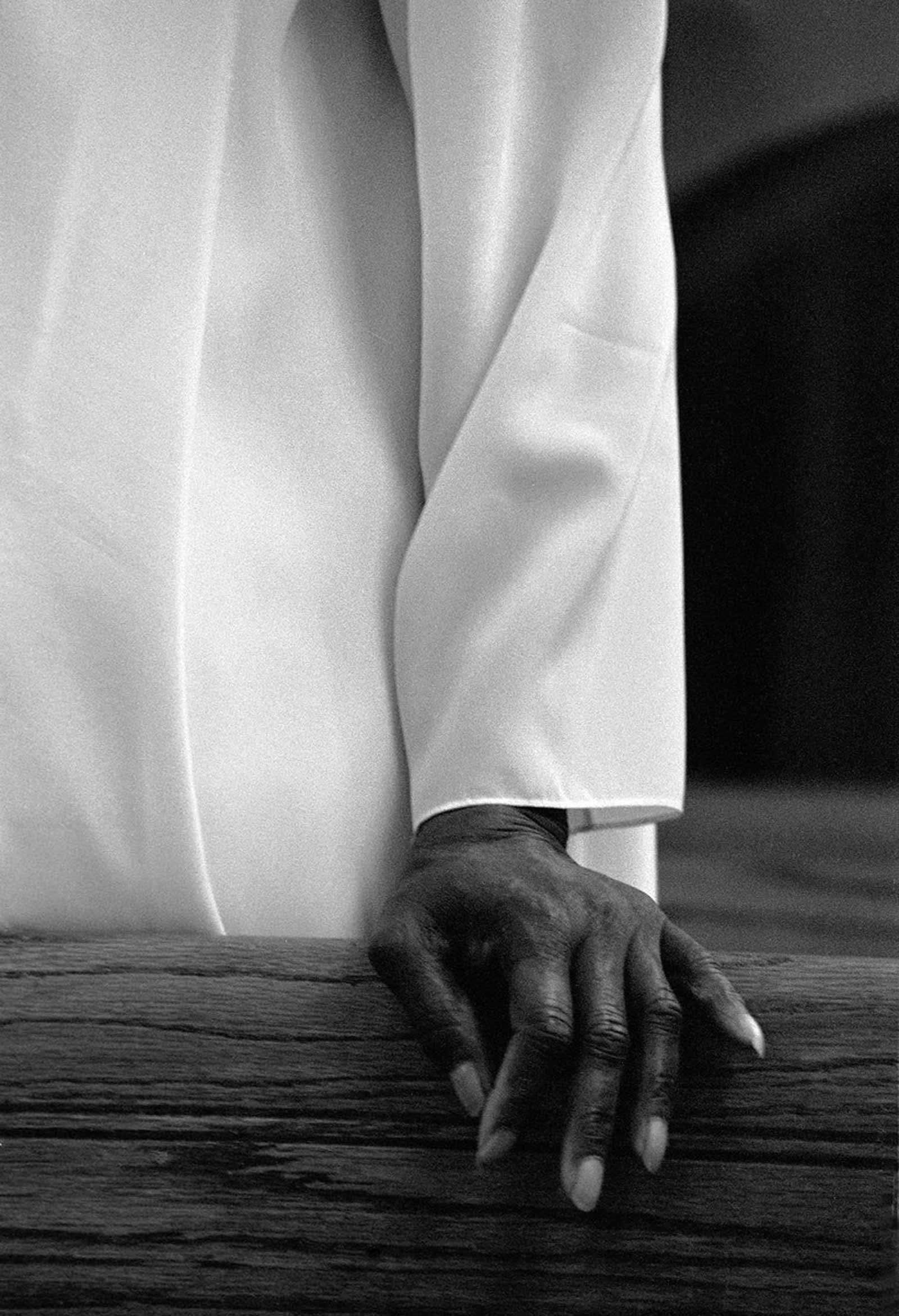

“New Brockton Church Pew, Springfield Baptist Church,” 1973. Photograph by Chester Higgins

When Higgins began making photographs for magazines and newspapers, in the late nineteen-sixties, he was one of a handful of Black photographers working in mainstream media. Much of the work produced in his thirty-nine years as a staff photographer at the Times was a concerted attempt to incorporate Black America into the world’s consciousness. “When I arrived at The New York Times in 1975, I felt the media was immune to any real comprehension of the world I knew well,” he wrote at the time of his retirement from the paper, in 2014. “I wanted to share the history and traditions of the people I grew up with.”

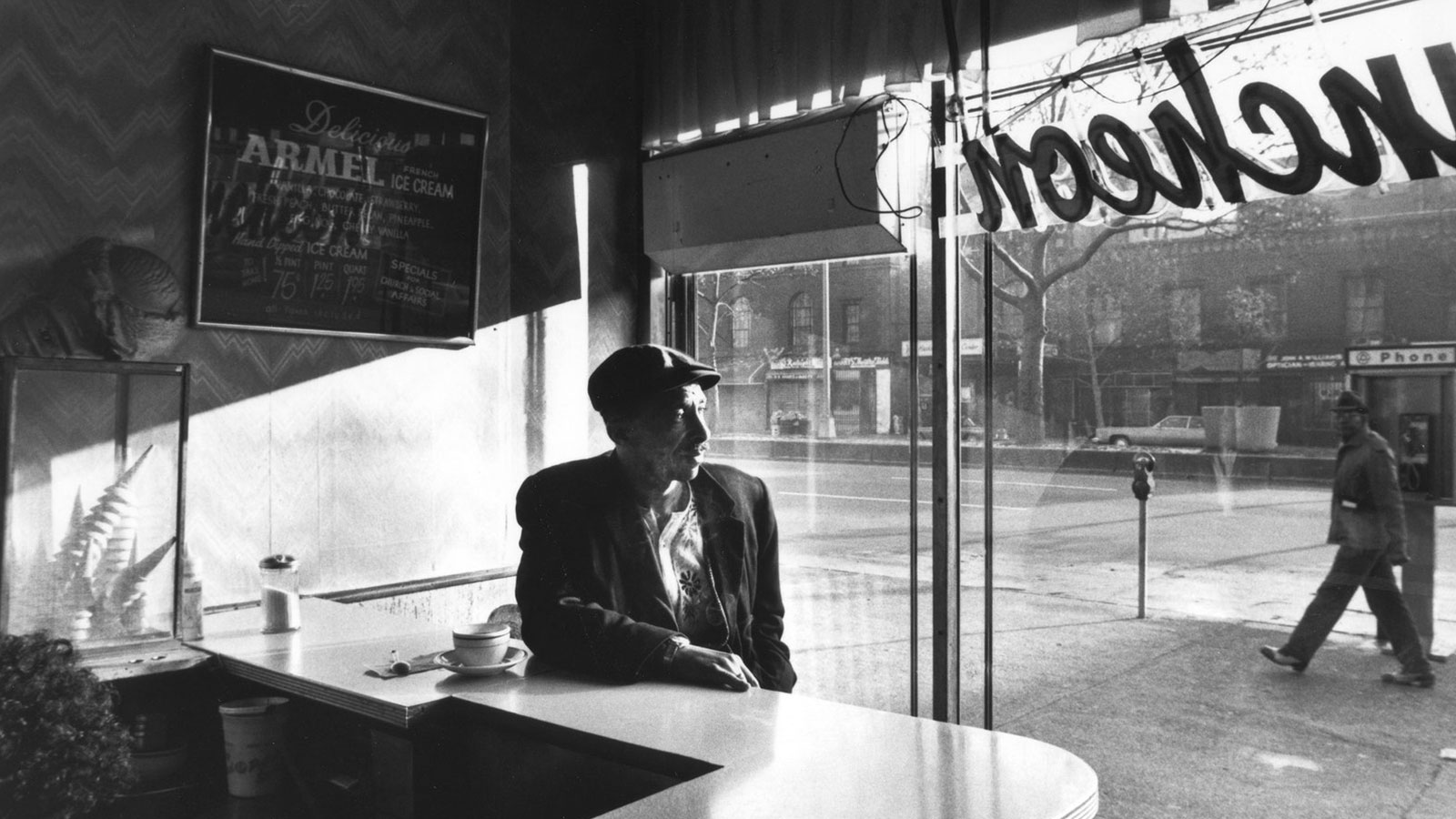

“Early Morning Coffee, Harlem,” 1974. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Adele’s, Harlem,” 1974. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Watching the Drag Race, Tuskegee, Alabama,” 1969. Photograph by Chester Higgins

Higgins grew up in New Brockton, Alabama, where, as a nine-year-old, he first encountered the spirit in his bedroom. He recalls waking in the middle of the night to a vision of a Black man in ancient clothing; the figure meditated, and then began to move toward him. “It said, ‘I come for you,’ ” Higgins told me, “and I screamed.” His elders understood the sighting as a call to faith, and he spent the following years preaching to congregations around his county as a youth minister.

“New Brockton, Alabama,” 1969. Photograph by Chester Higgins

It wasn’t until Higgins matriculated at the Tuskegee Institute, however, that he found his true vocation. He was studying business management and handling the budget for the campus newspaper. One semester, the paper was over budget, so Higgins had the idea of selling large photographic advertisements to local businesses to fill the gap. He commissioned P. H. Polk, Tuskegee’s official university photographer—and the only person Higgins knew with a camera—to take them.

Come press time, the pictures had yet to materialize, so Higgins went to Polk’s studio to track them down. He noticed old photographs that Polk had made during the Depression, portraits of Black farmers. Polk had lived on a busy road, a route where country folk would walk or drive mule-drawn wagons to sell their harvest at the weekend market. Every time a character caught Polk’s eye, he would hop off his porch and offer them five dollars to come pose for portraits inside his home studio. These images were revelatory for Higgins. In them, not only did he recognize people that could have easily been his “great aunts and uncles” but he also was struck by a certain stately quality in the treatment of the photo’s subjects.

Come press time, the pictures had yet to materialize, so Higgins went to Polk’s studio to track them down. He noticed old photographs that Polk had made during the Depression, portraits of Black farmers. Polk had lived on a busy road, a route where country folk would walk or drive mule-drawn wagons to sell their harvest at the weekend market. Every time a character caught Polk’s eye, he would hop off his porch and offer them five dollars to come pose for portraits inside his home studio. These images were revelatory for Higgins. In them, not only did he recognize people that could have easily been his “great aunts and uncles” but he also was struck by a certain stately quality in the treatment of the photo’s subjects.

“Father Swinging Son, Brooklyn,” 1972. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Lance and Lori, Manhattan,” 1990. Photograph by Chester Higgins

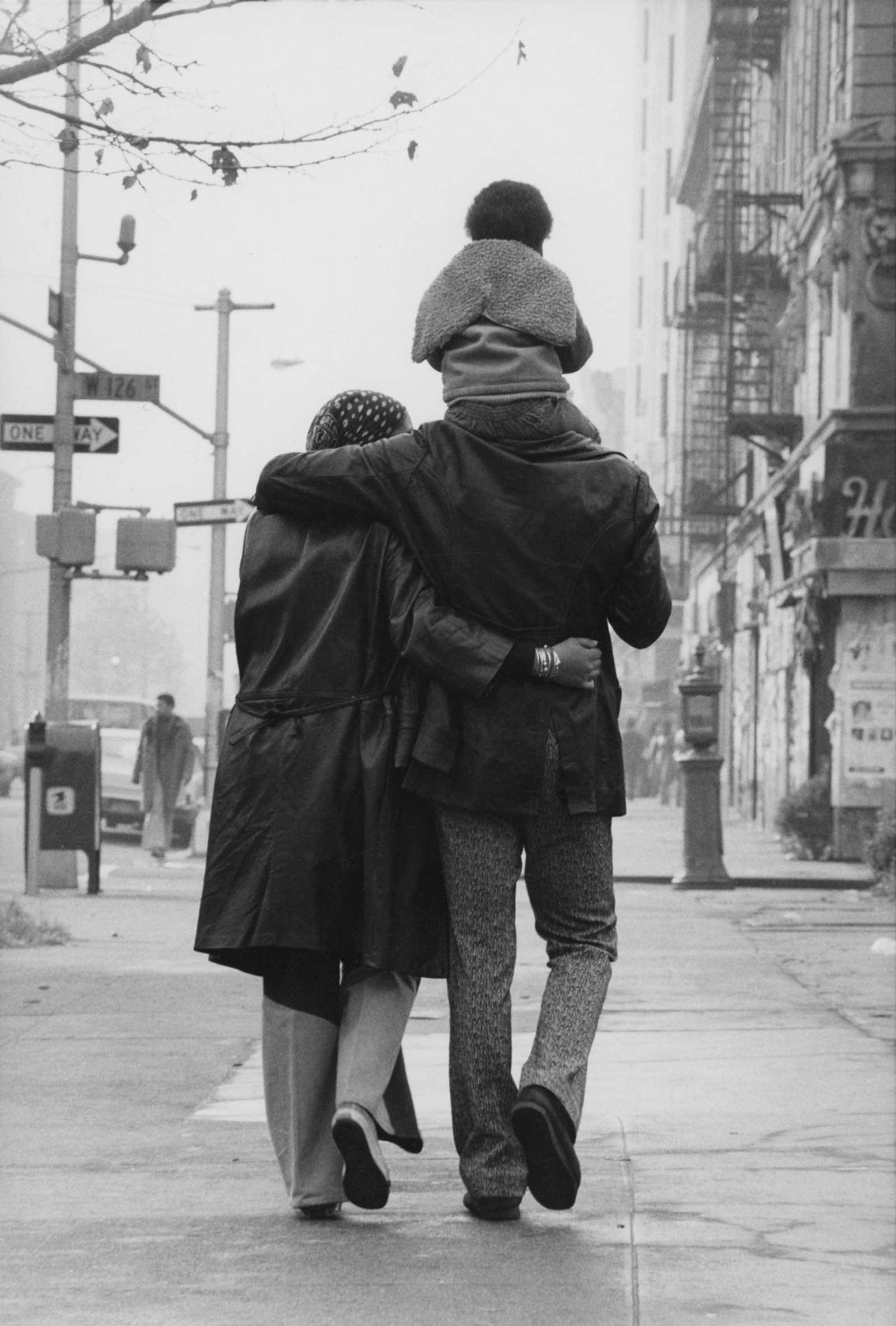

“Young Family Strolling, Harlem,” 1972. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“Nowhere were the elements of decency, dignity and virtuous character recorded in photographs of African Americans,” Higgins wrote in his 2004 photo-memoir, “Echo of the Spirit.” While he was growing up in southeast Alabama, in the fifties and sixties, the images of Black people in popular media that Higgins encountered were often of a particular bend; he disliked that “we were always seen as potential thugs or rapists.” And, back then, Higgins conceived of photography as a procedural craft rather than an artistic one. “It wasn’t tracing your emotions,” he told me. “It was objectifying something that had happened, some event, some cause.” It was only through his visit to Polk’s studio, and the marvel of those dignified portraits, that he began to realize the expressive—and corrective—potential of photography. The camera, he found, could be a vehicle for conveying the poise and esteem that emanated from the people around him and animated much of his early life.

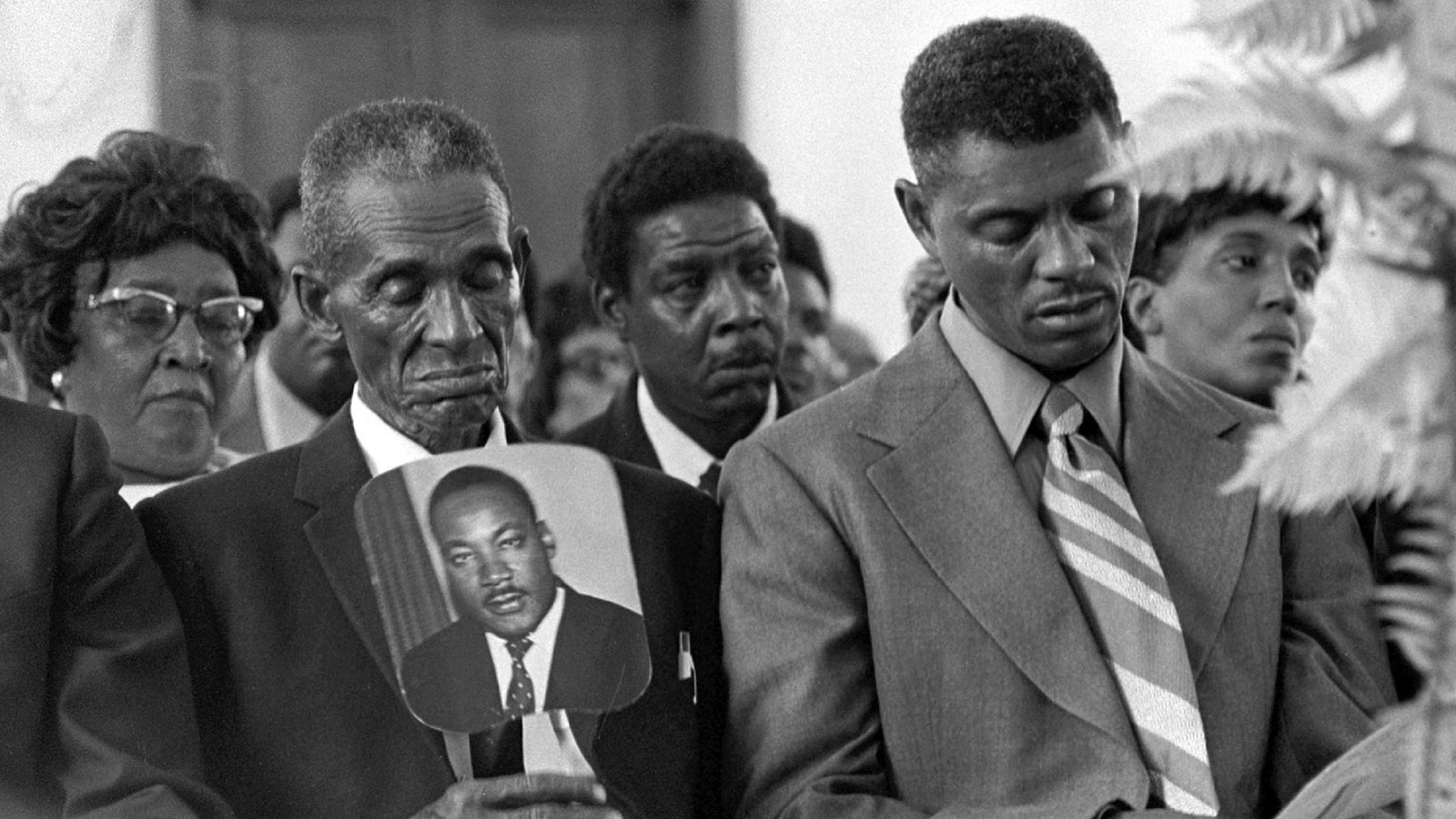

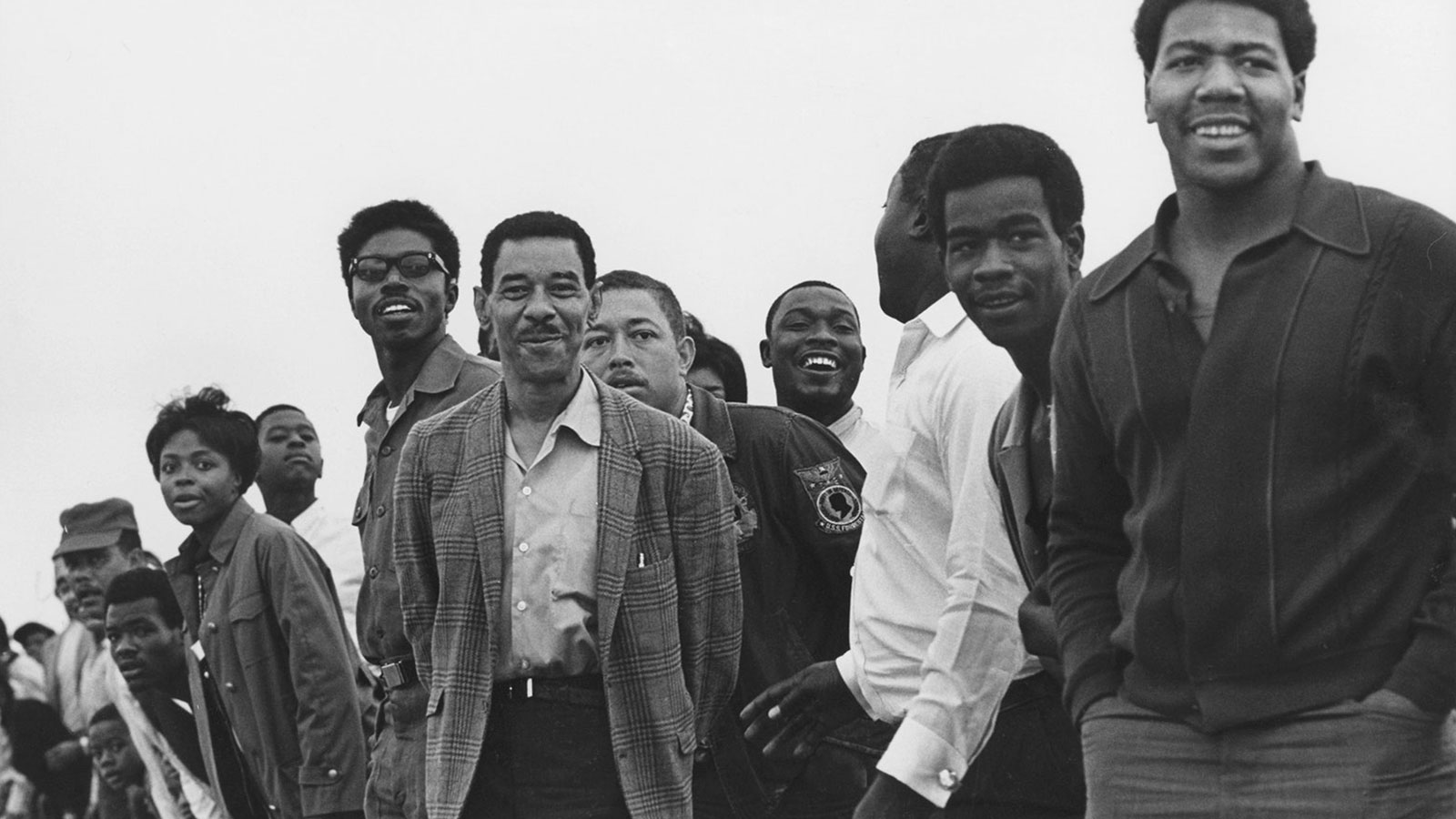

“The Indelible Spirit,” a retrospective that ran at Bruce Silverstein Gallery earlier this summer, catalogued Higgins’s career through the nineties, and, by extension, several key decades of American history. The show featured some early, post-college forays into street photography, filled with people and scenes around Tuskegee: a Black serviceman and his sweetheart smiling at Macon’s county fair, a crowd of drag-race attendees craning their necks to catch the action, a little boy sprawled on a dusty, unpaved road adjusting his bicycle tire. There was a selection from Higgins’s early freelance magazine work, a shot of a twenty-eight-year-old Jesse Jackson at a rally in California, from a 1970 issue of Look, and many cinematic stills from all over the African continent, where Higgins has been travelling annually for the past fifty years.

“Morning Chores, Ethiopia,” 1992. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“A Serving Dish, Ghana,” 1973. Photograph by Chester Higgins

The exhibit effectively surveyed the vast diasporic terrain contained in Higgins’s œuvre, charting his path out of the shadow of the sharecropping Deep South, to the campus of a historically Black university in the midst of the late-sixties social upheaval, to New York City in the nineteen-seventies, and finally back to the shores of Ghana and Senegal for a kind of ancestral communion. All along the way, his eye is trained on moments of calm, locating an inherent grace, style, and sublime beauty in the Black everyday.

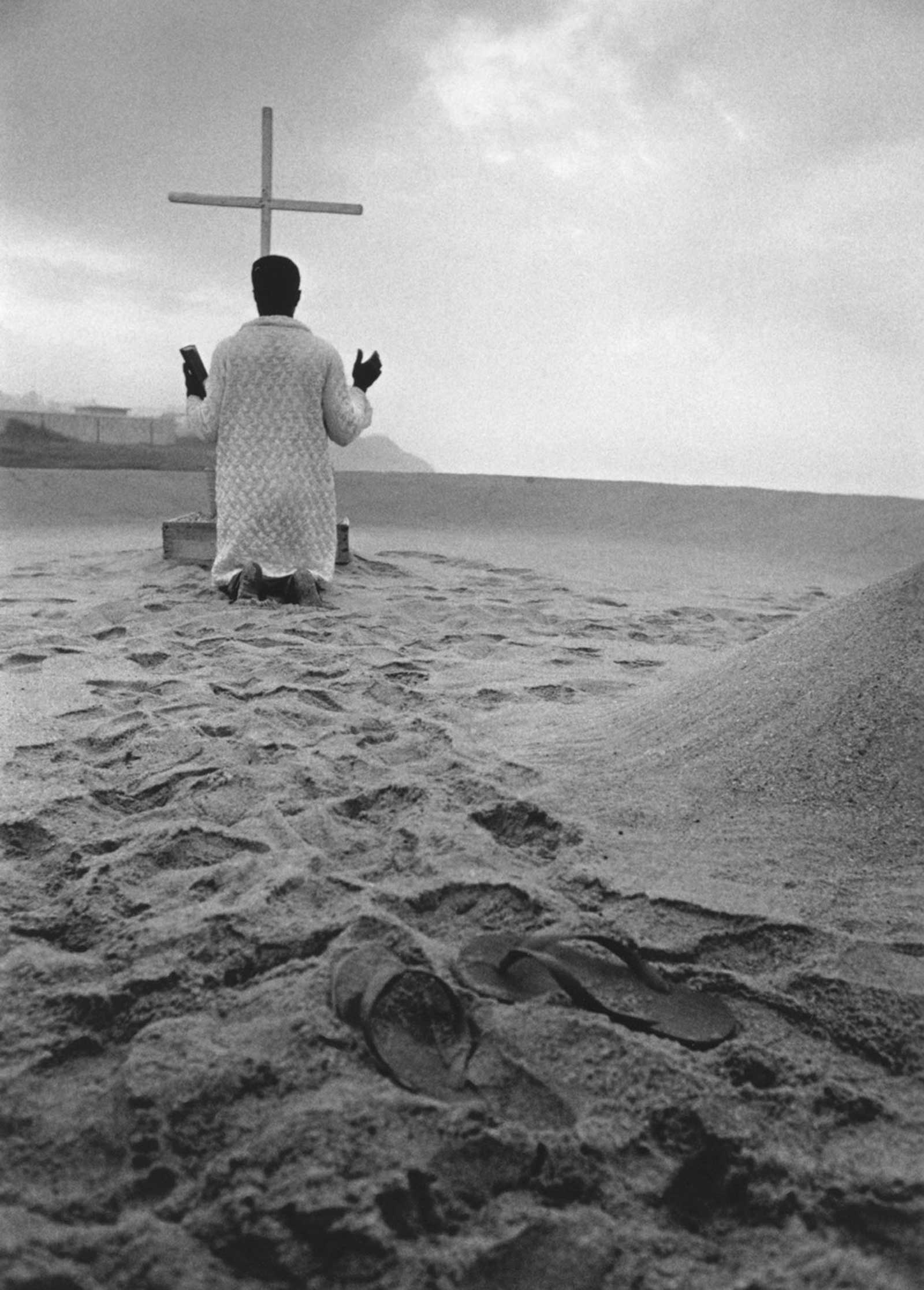

“Sunrise Prayer on Osu Beach, Accra, Ghana,” 1973. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“A Young Muslim Woman in Brooklyn,” 1990. Photograph by Chester Higgins

These elements manifest most strikingly in Higgins’s best-known pictures, such as “A Young Muslim Woman in Brooklyn” (1990), in which the niqab-clad subject’s very life force appears to beam through two oceanic, almond-shaped eyes. But they’re also present in lesser-knowns like “Adele’s, Harlem” (1974), a still that, in its clutter of bodies, half-empty ketchup bottles, and sweat-sheened foreheads, metonymizes the familiar afternoon rush at a neighborhood greasy spoon. Find them, yet again, in the quaint “Young Family Strolling, Harlem” (1972), where an impossible handsomeness seems to radiate from two parents walking arm in arm, a child sitting aloft on the father’s shoulders. “Sunrise Prayer on Osu Beach, Accra, Ghana” (1973), captured during his travels abroad, is of an entirely different flavor, but no less effective: a crowd of early-morning worshippers revel on the shore, their shadowy fervor reminiscent of a Goya painting.

“Harlem Baptist Church Lady,” 1986. Photograph by Chester Higgins

“The Door of No Return, Gorée Island, Dakar, Senegal,” 1971. Photograph by Chester Higgins

As Higgins and I chatted in his back yard, I took stock of the way his vocabulary for talking about race, art, and representation differed from my own. Admittedly, his insistence on showcasing the decency and dignity of Black people first struck me as a bit retrograde. I’m someone who grew up awash in all kinds of images of Black people—Black people in fashion magazines, Black people on reality television shows, Black people winning Wimbledon, Black people being President. Enmeshed as we are in many of the same issues that plagued the country when Higgins started his career, it can be easy to overlook progression, and those who have propelled it. “I single-handedly made sure there was a Kwanzaa picture in the paper for twenty-five years,” Higgins told me. “I made pictures of a Caribbean Festival on Eastern Parkway for decades.” The world we live in is one he pictured first.

Source: The New Yorker