By William Grimes / New York Times

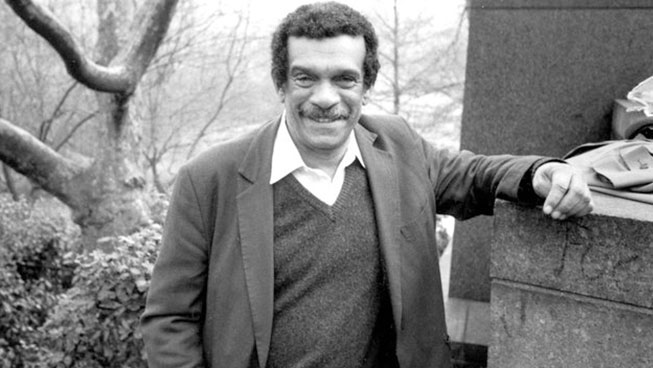

Derek Walcott, whose intricately metaphorical poetry captured the physical beauty of the Caribbean, the harsh legacy of colonialism and the complexities of living and writing in two cultural worlds, bringing him a Nobel Prize in Literature, died early Friday morning at his home near Gros Islet in St. Lucia. He was 87.

His death was confirmed by his publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. No cause was given, but he had been in poor health for some time, the publisher said.

Mr. Walcott’s expansive universe revolved around a tiny sun, the island of St. Lucia. Its opulent vegetation, blinding white beaches and tangled multicultural heritage inspired, in its most famous literary son, an ambitious body of work that seemingly embraced every poetic form, from the short lyric to the epic.

With the publication of the collection “In a Green Night” in 1962, critics and poets, Robert Lowell among them, leapt to recognize a powerful new voice in Caribbean literature and to praise the sheer musicality of Mr. Walcott’s verse, the immediacy of its visual images, its profound sense of place.

He had first attracted attention on St. Lucia with a book of poems that he published himself as a teenager. Early on, he showed a remarkable ear for the music of English — heard in the poets whose work he absorbed in his Anglocentric education and on the lips of his fellow St. Lucians — and a painter’s eye for the particulars of the local landscape: its beaches and clouds; its turtles, crabs and tropical fish; the sparkling expanse of the Caribbean.

In the poem “Islands,” from the collection “In a Green Night,” he wrote:

I seek,

As climate seeks its style, to write

Verse crisp as sand, clear as sunlight,

Cold as the curled wave, ordinary

As a tumbler of island water.

He told The Economist in 1990: “The sea is always present. It’s always visible. All the roads lead to it. I consider the sound of the sea to be part of my body. And if you say in patois, ‘The boats are coming back,’ the beat of that line, its metrical space, has to do with the sound and rhythm of the sea itself.”

There was nothing shy about Mr. Walcott’s poetic voice. It demanded to be heard, in all its sensuous immediacy and historical complexity.

“I come from a place that likes grandeur; it likes large gestures; it is not inhibited by flourish; it is a rhetorical society; it is a society of physical performance; it is a society of style,” he told The Paris Review in 1985. “I grew up in a place in which if you learned poetry, you shouted it out. Boys would scream it out and perform it and do it and flourish it. If you wanted to approximate that thunder or that power of speech, it couldn’t be done by a little modest voice in which you muttered something to someone else.”

Mr. Walcott’s art developed and expanded in works like “The Castaway,” “The Gulf” and “Another Life,” a 4,000-line inquiry into his life and surroundings, published in 1973. The Caribbean poet George Lamming called it “the history of an imagination.”

Mr. Walcott quickly won recognition as one of the finest poets writing in English and as an enormously ambitious artist — ambitious for himself, his art and his people.

He had a sense of the Caribbean’s grandeur that inspired him to write “Omeros,” a transposed Homeric epic of more than 300 pages, published in 1990, with humble fishermen and a taxi driver standing in for the heroes of ancient Greece.

Two years later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. The prize committee cited him for “a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment.”

It continued: “In his literary works Walcott has laid a course for his own cultural environment, but through them he speaks to each and every one of us. In him, West Indian culture has found its great poet.”

As a poet, Mr. Walcott plumbed the paradoxes of identity intrinsic to his situation. He was a mixed-race poet living on a British-ruled island whose people spoke French-based Creole or English.

In “A Far Cry From Africa,” included in “In a Green Night” — his first poetry collection to be published outside St. Lucia — he wrote:

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?

Derek Alton Walcott was born on Jan. 23, 1930, in Castries, a port city on the island of St. Lucia. His father, Warwick, a schoolteacher and watercolorist, died when he was an infant, and he was raised by his schoolteacher mother, the former Alix Maarlin.

Both his parents, like many St. Lucians, were the products of racially mixed marriages. Derek was raised as a Methodist, which made him an exception on St. Lucia, a largely Roman Catholic island, and at his Catholic secondary school, St. Mary’s College.

His education was Anglocentric and thoroughly traditional. “I was taught English literature as my natural inheritance,” he wrote in the essay “The Muse of History.” “Forget the snow and daffodils. They were real, more real than the heat and oleander, perhaps, because they lived on the page, in imagination, and therefore in memory.”

He published his first poem at 14, in a local newspaper. With a loan from his mother, he began publishing his poetry in pamphlets while still at St. Mary’s. His early models were Marlowe and Milton.

At the University of the West Indies in Mona, Jamaica, where he majored in French, Latin and Spanish, he began writing plays, entering into a lifelong but rocky love affair with the theater. His first play, about the revolutionary Haitian leader Henri Christophe, was produced in St. Lucia in 1950.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in 1953, Mr. Walcott taught school in St. Lucia, Grenada and Jamaica while continuing to write and stage plays. His verse dramas “Ione” and “Sea at Dauphin” were produced in Trinidad in 1954. “Ti-Jean and His Brothers,” a retelling of a Trinidadian folk tale in which Lucifer tries to steal the souls of three brothers, was produced in Trinidad in 1958.

Mr. Walcott studied directing with José Quintero in New York for a year and, on returning to the West Indies, founded a repertory company, the Little Carib Theater Workshop, which in the late 1960s became the Trinidad Theater Workshop. One of the group’s first productions was Mr. Walcott’s “Malcochon.”

His best-known play was “Dream on Monkey Mountain,” which received an Off Broadway production in 1971. He later wrote the book and collaborated with the singer and songwriter Paul Simon on the lyrics for “The Capeman,” a musical about a Puerto Rican gang member who murdered three people in Manhattan in 1959. The show opened at the Marquis Theater in 1998 and closed after 68 performances, becoming one of the most expensive flops in Broadway history.

With the publication of “In a Green Night” in 1962, Mr. Walcott captured the attention of British and American critics. Robert Lowell in particular was enthusiastic, and served as a point of entry to the American literary world. With each succeeding collection — “Selected Poems” (1964), “The Castaway” (1969), “The Gulf” (1970) and “Sea Grapes” (1976) — Mr. Walcott established himself as something more than an interesting local poet.

“Aficionados of Caribbean writing have been aware for some time that Derek Walcott is the first considerable English-speaking poet to emerge from the bone-white Arcadia of the old slaveocracies,” the poet and critic Selden Rodman wrote in a review of “The Gulf” in The New York Times Book Review. “Now, with the publication of his fourth book of verse, Walcott’s stature in the front rank of all contemporary poets using English should be apparent.”

The lyric strain in Mr. Walcott’s poetry never disappeared, but he increasingly took on complex narrative projects and expanded his vision of the Caribbean to accommodate an epic treatment of the themes that had always engaged him. The artistic self-portrait of “Another Life,” with its rich, metaphor-heavy intertwining of the artist’s developing sensibility and the lush landscape of St. Lucia, set the bar for Mr. Walcott’s later, increasingly ambitious poetry.

In “Omeros” — the title is the modern Greek word for Homer — Mr. Walcott cast his net wide, embracing all of Caribbean history from time immemorial, with special attention to the slave trade, and refracting its story through Homeric legend. In his hands, the Caribbean became not a backwater but a crossroads — what the scholar Jorge Hernandez Martin, writing in the magazine Americas in 1994, called “a dispersion zone, a sort of switchboard with input from and output to other parts of the world.”

Travel and exile were constants in Mr. Walcott’s poetry. “Tiepolo’s Hound” (2000) presented a dual portrait of the author and the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, who spent his childhood in the Caribbean before being transplanted to Paris. Like his father, Mr. Walcott was an accomplished watercolorist; his landscape paintings appear on his book jackets, and in “Tiepolo’s Hound” they are interspersed through the book.

The wanderings in “Omeros” were rivaled by Mr. Walcott’s own zigzag itinerary as a teacher and lecturer at universities around the world. He taught at Boston University from 1981 until retiring in 2007, dividing his time among Boston, New York and St. Lucia but constantly en route.

“The Prodigal” (2004), a late-life summation with a distinctly elegiac undercurrent, offered a glimpse of the author’s restless movements, which take him, in the course of the poem, to Italy, Colombia, France and Mexico. “Prodigal, what were your wanderings about?” he wrote. “The smoke of homecoming, the smoke of departure.”

Mr. Walcott’s three marriages ended in divorce. His survivors include his longtime companion, Sigrid Nama; a son, Peter; two daughters, Anna Walcott-Hardy and Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw; and several grandchildren. His twin brother, Roderick, a playwright, died in 2000.

In 2009, Mr. Walcott was proposed for the honorary post of professor of poetry at Oxford University. His candidacy was derailed when academics at Oxford received an anonymous package containing photocopied pages of a book describing allegations of sexual harassment brought by a Harvard student decades earlier. Mr. Walcott withdrew his name.

“I am disappointed that such low tactics have been used in this election, and I do not want to get into a race for a post where it causes embarrassment to those who have chosen to support me for the role or to myself,” he told The Evening Standard of London. He added, “While I was happy to be put forward for the post, if it has degenerated into a low and degrading attempt at character assassination, I do not want to be part of it.”

Mr. Walcott was always conscious of writing as a man apart, from a corner of the world whose literature was in its infancy. This peculiar position, he argued, had its advantages. “There can be virtues in deprivation,” he said in his Nobel lecture, describing the “luck” of being present in the early morning of a culture.

“For every poet, it is always morning in the world,” he said. “History a forgotten, insomniac night; History and elemental awe are always our early beginning, because the fate of poetry is to fall in love with the world, in spite of History.”