By Walter Fields

The “Big Four” civil rights leaders meeting with President Lyndon Johnson in the Oval Office.

While there were allusions to the partisan preferences of civil rights leaders during the 1950s and 1960s, there was never a public expression in the advocacy of the ‘Big Four’ – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, Whitney Young of the National Urban League and James Farmer of CORE – that made partisanship the centrifugal force of their demands for justice and equality. It was the strength of their demands for constitutional protections, based upon the equal application of rights, that served as the basis for their making no distinction of the parties controlling the White House or Congress. It is a lesson we need to re-learn as a movement that once rested upon the idea of full emancipation and citizenship has been compromised by the accommodations we make in deference to partisanship.

Today, the voice of Black Americans in our quest for liberation has been muted and made secondary to the jockeying of the two major political parties for power. Too many Black Americans readily identify as a Democrat or Republican without first coming to terms with what should be demanded of both parties. We have become so invested in the welfare of each of the primary political parties that remaining loyal has become more important than making claims upon political elites and challenging structures of inequity. Our political engagement is consumed by a loyalty test that never serves our interest and is then used against us; by manipulating Black voters through sentimental cultural appeals using our history and institutions to guilt us into support.

Familiarity has really killed the movement. We have become so cozy, so seduced by the approximation to power that we often engage against our own interest. In many instances we won’t even raise objections or offer critiques of the policies of political parties for fear of being labeled a dissenter. This is particularly true in the Democratic Party as any deviation from the party line by African-Americans is deemed blasphemous. The ‘party line’ is deemed sacrosanct and those Blacks who dare take exception are met with swift condemnation.

Our obsession with partisanship is understandable since the two major political parties have shown some decency toward us depending upon the moment in history. We have become afflicted through the over reliance on the benevolence of a particular political party, while making its opposition the object of our derision. When, in fact, we only become acceptable to either political party when our support facilitates their electoral advantage. Few remember that long past Reconstruction the Republican Party enjoyed the support of the Black electorate. It took Minnesota’s Hubert Humphrey to challenge his Democratic Party at their 1948 convention before it started to evaluate its racially constructed platform. In 1956 President Eisenhower received about 39% of the Black vote and four years later his vice president, Richard Nixon, received 32% of the Black vote in the 1960 presidential election against Democrat John F. Kennedy. Today, the tables have turned in party identification but African-Americans still remain disadvantaged at many levels, and marginalized by our current party structure.

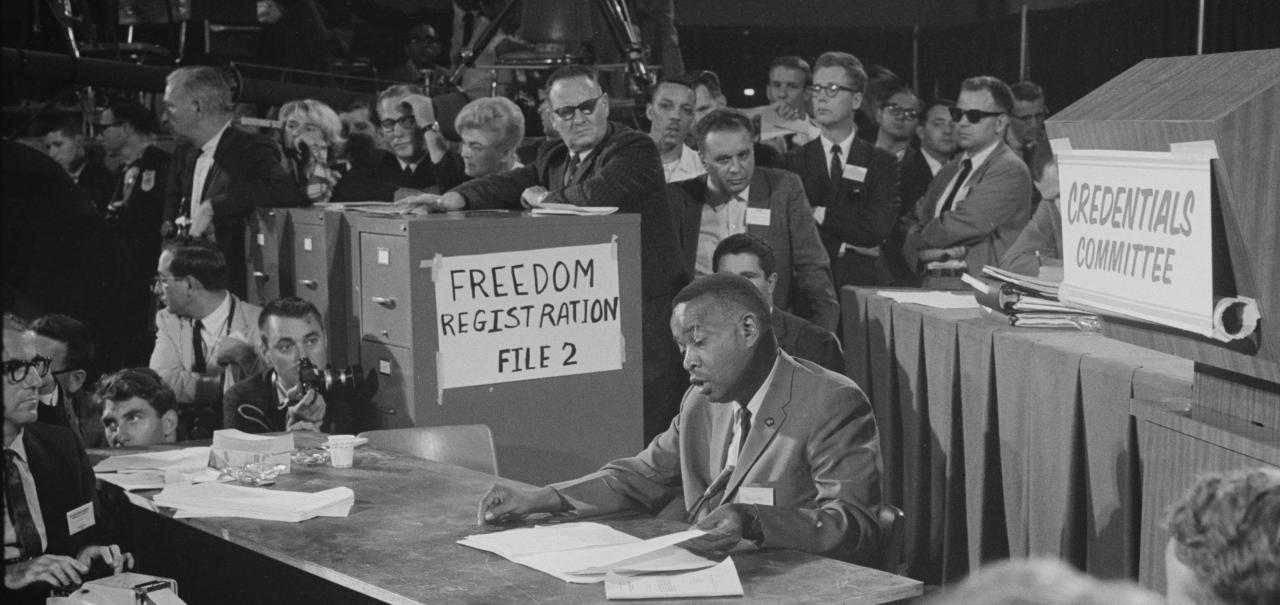

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s Aaron Henry testifying before credentials committee at 1964 Democratic convention

In many ways the blind allegiance and loyalty test is also applicable to our elected officials. As the presence of African-Americans increased in Congress, a direct outcome of the on-the-ground fight waged for voting rights, rather than reform institutions that traditionally worked against us, Black elected officials have become transfixed on the hoarding of power for power’s sake. Where the first generation of Black members on the Hill attempted to operate within the framework of the unofficial theme of the Congressional Black Caucus – “No Permanent Friends, No Permanent Enemies. Just Permanent Interests” – that understanding has given way to a self-centeredness that not all, but many of our representatives in Congress exhibit. So much of their behavior is theatrics it is hard to distinguish earnest and meaningful ‘representation’ and role playing for the sake of job security. And while the partisan control of Congress does factor into the substantive work one can do, too often the role of loyal opposition and moral conscious for our community is sacrificed to the partisan priorities of the party that more often exclude the concerns and needs of African-Americans.

Judging from my literature review through the years, conversations with participants in the civil rights movement, scholarly engagement in political science and public policy, and work in the field – there is nothing to suggest that partisanship was the measure of success intended by activists from abolitionism to the modern civil rights campaign. We have lost the essence of the lives of Douglass, Tubman, Garvey, King, Malcolm, Hamer and others by focusing so much of our attention on party identity and not systemic change. Political parties as presently construed are closed systems, controlled by moneyed elites only concerned with maintaining economic control of the nation through the manipulation of media and seemingly benign appeals to party loyalty.

The 2016 election cycle represents the beginning of a new political reality for African-Americans. I see it clearly. Though both party’s establishment is under fire, for the Democratic Party, where the majority of Black votes are lodged, the voices of millennials are expressing a disbelief in the value of partisan identification. The real question for the Democratic Party is not whether Senator Sanders or Senator Clinton will be the nominee; though there are some major differences between the two either candidate can take down Donald Trump or Senator Ted Cruz. The real question is how the bloc of emerging Black voters decides to organize, communicate and activate their dissatisfaction with a system they consider broke and elected officials they deem irrelevant, and in some cases, betrayers to our community.

Our hope is in a re-thinking of how we engage politically and economically, and ending the addiction to partisanship that confuses elections as an end, and not a means to securing the freedoms our ancestors’ physical and mental anguish, and labor, bequeathed us.

Walter Fields is Executive Editor of NorthStarNews.com.