A Post podcast reveals eyewitness accounts and other evidence that raise new questions about the U.S. role in this mystery

By Martine Powers, Ted Muldoon and Rennie Svirnovskiy, The Washington Post —

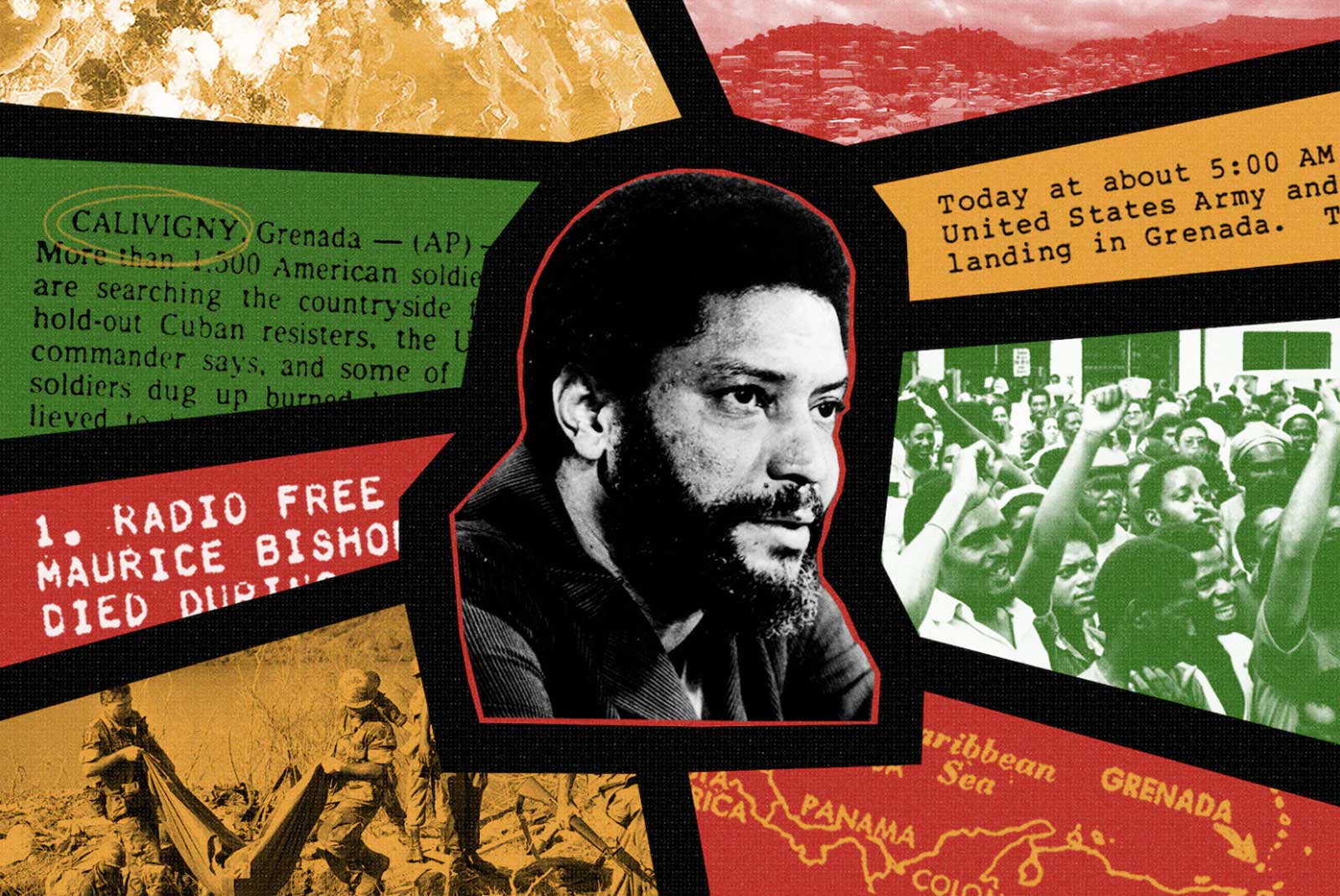

It’s a mystery that has haunted a Caribbean island nation since the height of the Cold War: What happened to the body of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop?

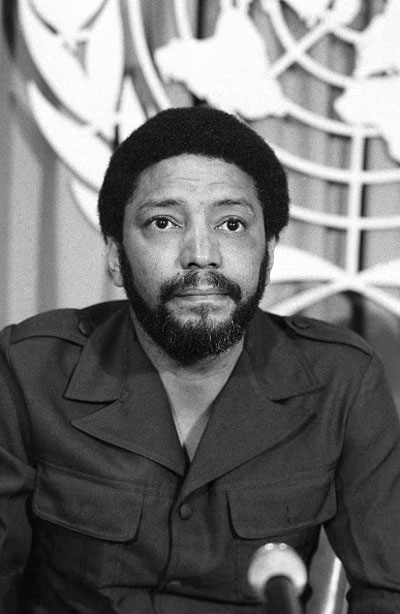

Grenada’s Prime Minister Maurice Bishop at press conference.

Bishop, the revolutionary leader of Grenada, was executed during a coup in October 1983. Seven cabinet members and supporters were killed alongside him. In the aftermath of the coup and a subsequent invasion by U.S. troops, the remains of all eight people disappeared. For decades, unanswered questions about the missing remains have devastated family members and left Grenadians struggling to close the most traumatic chapter in their nation’s history.

Now, new eyewitness accounts and U.S. government documents suggest that the United States played a larger role in the recovery and examination of the remains than has been previously reported, and could hold the key to solving the mystery of what happened to them. These revelations were first reported in The Washington Post’s investigative podcast series, “The Empty Grave of Comrade Bishop.”

They include satellite photos that suggest the area where Bishop and the others were believed to have been buried initially was inadvertently bombed by U.S. forces, an interview with an eyewitness who said that Bishop’s body was exhumed by U.S. troops and flown to an American ship, and a report that tissue samples from the remains were taken to the United States for testing.

“We were definitely involved with this,” said Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) in the podcast, after reviewing The Post’s findings. “To be dismissive and to pretend that it didn’t happen or that we had no involvement is just a stain on our country. And this administration has the moment and the opportunity to make this right.”

Lee has sought answers from the Defense Department about Bishop’s missing remains for years. She wrote again in October to Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin asking him to explain, among other things, the U.S. government’s process for handling remains, and why the department says it has no records available in this case. “The United States government has failed to provide a complete and final accounting of what happened to Bishop’s remains once they came into U.S. custody,” Lee told The Post.

After hearing about The Post’s findings, the daughter of one of the men killed with Bishop said the U.S. needs to reinvestigate its role in what happened to the bodies. “They do have that responsibility,” said Pamela Bullen Cherebin. Her father was Evelyn Bullen, a close friend of Bishop’s. “And not to point the finger to punish, but for history, documentary purposes, to let it be known that this was done and it was a mistake or whatever. ‘We are sorry.’ … They have a responsibility. Why can’t they be held accountable for their actions?”

In Grenada, the podcast was the No. 1 show on Apple Podcasts for weeks after its release. “Martine’s investigations confirmed what we suspected all along,” said Terrence Marryshow, executive and spokesperson of the Maurice Bishop and October 19 Martyrs Foundation, which organizes events to commemorate Bishop’s legacy, in an email.Marryshow said that while ultimate culpability rests with the men who killed Bishop and his allies, the podcast highlighted “the complicity of the U.S. administration in first mishandling and then covering up the findings over the last 40 years.” He thanked Powers for “bringing us closer to closure.”

- A personal photograph taken by CIA analyst David Bush on Nov. 2, 1983, in Calivigny, Grenada. This is the site of the Calivigny Barracks, which was bombed by the United States. Maurice Bishop and his cabinet members’ bodies are believed to have been buried nearby after they were assassinated on Oct. 19, 1983. (David Bush)

- A personal photograph taken by CIA analyst David Bush on Nov. 2, 1983, in Calivigny at the Calivigny Barracks. (David Bush)

The U.S. government has said over the years that it has no information about the whereabouts of the remains, a position that both the State Department and the Pentagon maintained to The Post.

In Grenada, many people for years have suspected that the U.S. government was somehow involved in disappearing the remains of a beloved but controversial leader who befriended Communist governments and traded barbs with President Ronald Reagan.

Bishop came to power in 1979 after overthrowing Grenada’s leader, Sir Eric Gairy, in a nearly bloodless coup. Eloquent and charismatic, the trained lawyer snubbed his nose at what he sarcastically called the “big, powerful, mighty United States” while championing Pan-African solidarity. Bishop and his Marxist-Leninist party transformed the former British colony, investing in free public education and jobs programs. To many, Bishop’s leadership represented an inspiring vision of Black power and possibility.

He also suspended the constitution and warned that anyone who threatened the revolution would be “ruthlessly crushed.” An estimated 3,000 people were arbitrarily detained under his rule. Some later said they had been beaten and tortured in jail.

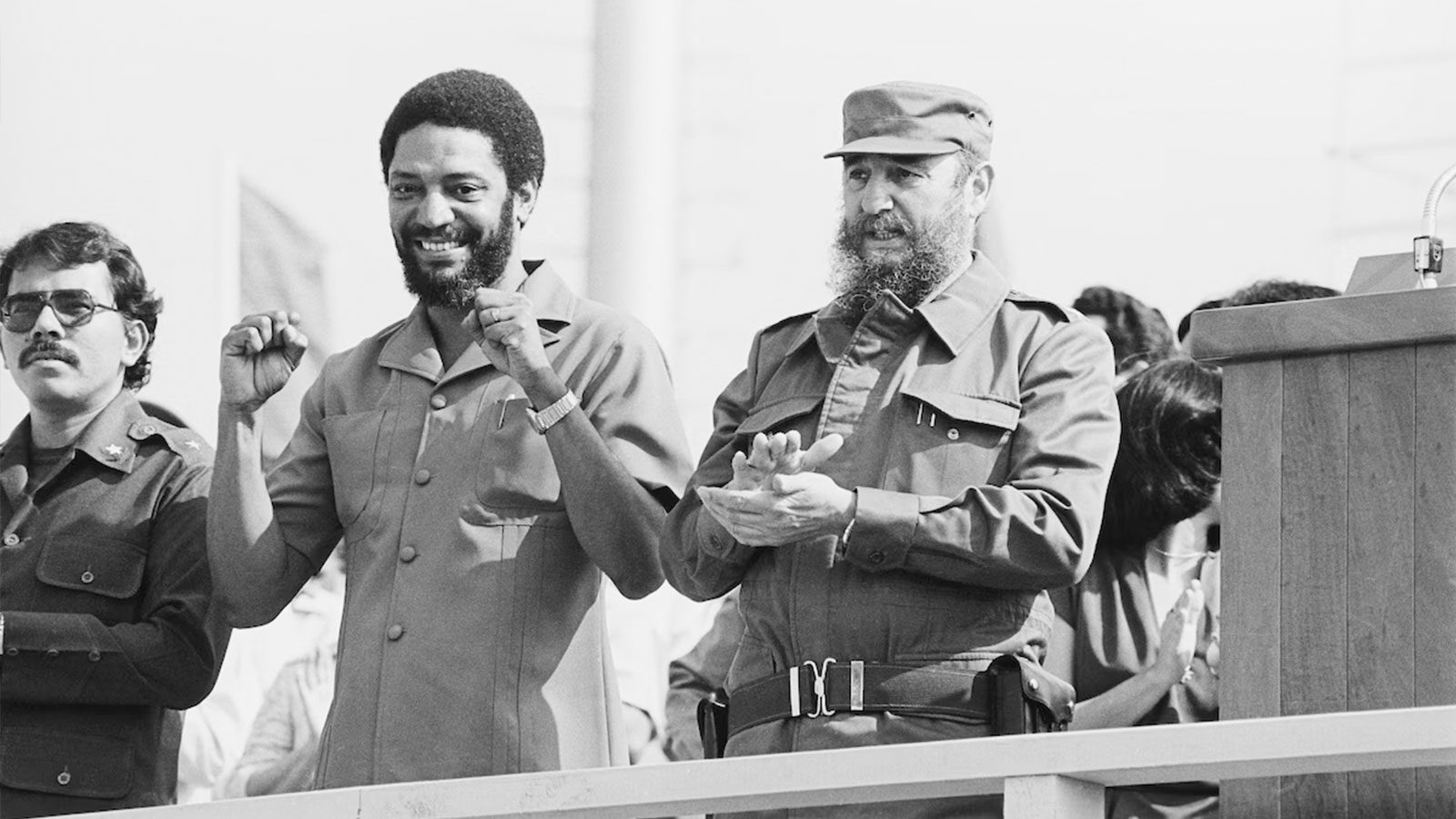

Fidel Castro, right, attends a mass May Day rally May 1, 1980, with Bishop, center, and Daniel Ortega, a member of the Nicaraguan Sandinista junta. Cuban officials said nearly 1 million attended the rally at the Plaza of the Revolution to hear denunciations of the refugees leaving Cuba and the United States.

Bishop developed close ties to Cuba and the Soviet Union, which provided weapons and military training. The United States feared Grenada could be used as a base from which to launch an attack. It cut off diplomatic ties to the island nation and froze economic aid. In March 1983, Reagan highlighted the threat Grenada posed in a televised address to the nation. “The Soviet-Cuban militarization of Grenada, in short, can only be seen as power projection into the region,” he said.

At the same time, tensions within Bishop’s government began to fester. A rival faction attempted to take control. On Oct. 19, 1983, Bishop was lined up in front of a wall and executed with machine guns. Killed alongside him were Jacqueline Creft, education minister; Norris Bain, housing minister; Unison Whiteman, foreign minister; and close supporters Fitzroy Bain, Keith Hayling, Evelyn Bullen and Evelyn Maitland.

In later court testimony and interviews, those accused of plotting and carrying out the killings would offer the following account of what happened after the executions: Members of the military had driven the eight bodies to a military training camp on an isolated peninsula known as Calivigny. Their remains were put in a pit with tires and other debris, and set on fire.

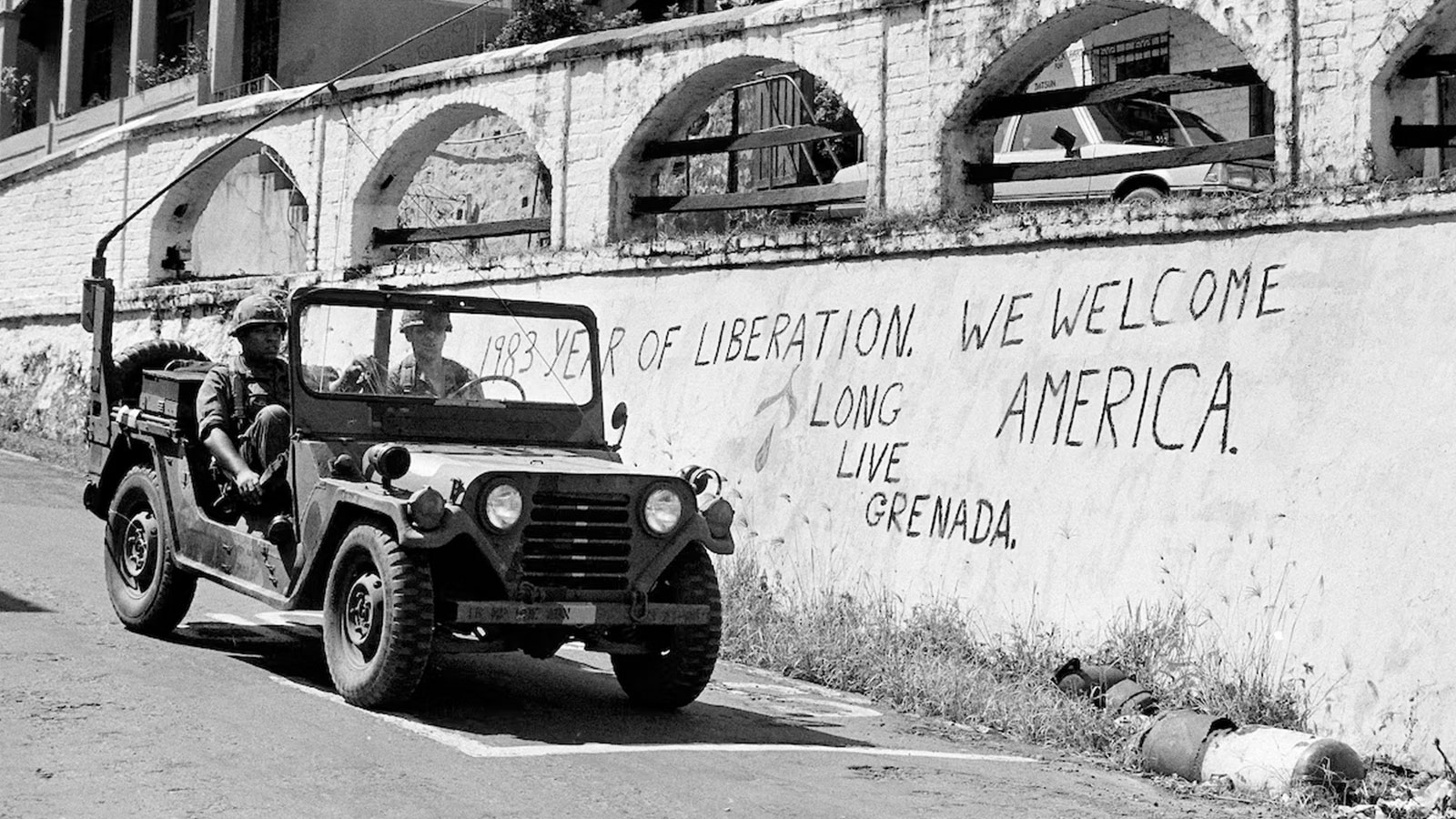

Bishop’s death shocked followers around the world. Six days later, on Oct. 25, Reagan ordered U.S. troops to invade Grenada along with a coalition of Caribbean nations, both to rescue U.S. citizens, many of them students attending medical school on the island, and to restore democracy.

U.S. members of the multinational peacekeeping force drive their jeep past a wall with graffiti welcoming Americans in St. George’s, Grenada, Nov. 10, 1983. (Bill Haber/AP)

The troops arrested those suspected of the killings and took control of the island, quickly overpowering Grenadian forces and a small contingent of Cuban soldiers. U.S. soldiers discovered the pit at Calivigny and excavated the remains Nov. 8. News reports at the time said the soldiers suspected they had found Bishop’s body. But after that, the headlines stopped. For many Grenadians, including the families of Bishop and those killed with him, that was the last they heard about the bodies of their loved ones.

In 2000, a group of Grenadian high school students working on a class project obtained a report from an anatomy professor who participated in a forensic examination of recovered remains from Calivigny by a U.S. military team in November 1983 at an anatomy lab in Grenada. But the report said the remains had been too decomposed and damaged to determine whether Bishop’s body had been among them. It also said that the U.S. military had apparently given those remains to a local funeral home for burial. But by then, the funeral director had died and did not record what happened to the remains or tell anyone else.

During a two-year investigation, Post reporters interviewed more than 100 people, including Grenadians involved in the burial at Calivigny, as well as current and former U.S. military members and other government officials who were in Grenada after the invasion. Among the findings:

- During the U.S. invasion, on Oct. 27, the military bombed Calivigny in advance of a raid on the area. The goal, one soldier told The Post, was to “make it a parking lot.” Satellite images obtained by The Post show bomb damage to the area near the pit. It is unclear whether the pit itself was hit by the bombs or whether the bodies themselves were damaged.

- After the bombing, U.S. Army Rangers stormed Calivigny and stayed on guard that night, positioned in pits in the area. In the morning, one realized he had slept on human remains, two Rangers later told The Post. The Rangers said they reported the bodies to their commander.

- A CIA officer, David Bush, told The Post that he came across a gravesite at Calivigny on Nov. 2, six days before the exhumation, and reported it to officials in Washington, D.C.

- On Nov. 6, a State Department situation report said that a gravesite had been found in Grenada and that it was “suspected that this site may contain the bodies of Bishop, his cabinet members, and other civilians.”

- A former Jamaican military intelligence officer, Earl Brown, who was present for the Nov. 8 exhumation by U.S. troops, told The Post that the Americans identified the bodies of Bishop, Creft, Whiteman and two others with the help of a witness and clothing that had not been entirely burned. U.S. troops, he said, put each body in a bag, tagged them with their names and placed them on a helicopter. Brown said he was told by the American commander that they would be taken to a U.S. naval ship for a forensic examination.

- Brown said that he took notes and photographed the recovery of the remains. Those records, he said, remain with the Jamaica Defense Force.

- A person with direct knowledge of the U.S.-led exam performed in the anatomy lab on the island told The Post that tissue samples were collected and taken back to the United States, including a jawbone, potentially a tooth, pieces of skin and hair, and parts of what they thought might have been internal organs. The samples, if they still exist, could be tested for DNA.

- Grenada’s attorney general, Claudette Joseph, said that the acting head of government after the U.S. invasion, Sir Paul Scoon, provided private testimony to Grenada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in which he allegedly stated that he was told by the U.S. government that Bishop’s body had been buried at sea.

Members of the U.S. Army graves registration team carry a body bag containing the remains of the one of three to four bodies fond in a shallow grave at the Calivigny, Grenada, military training compound on Nov. 8, 1983. (Pete Leabo/AP)

During the course of the investigation, The Post learned that there are other records and photographs that could shed new light on what happened. So far, The Post’s attempts to obtain them through public records requests have been unsuccessful.

“We have no knowledge of or information about the remains of Prime Minister Bishop,” the State Department said in a statement.

“The Department was not able to find any existing records or documents related to this case that can confirm the information presented,” said Cmdr. Nicole Schwegman, a spokeswoman for Department of Defense, after reviewing evidence presented by The Post.

Also see

‘The Empty Grave of Comrade Bishop’: Podcast episode guide

‘The Empty Grave of Comrade Bishop’: Podcast episode guide — Listen to podcast episodes

Source: The Washington Post

Martine Powers is the senior host of “Post Reports,” The Washington Post’s flagship daily news podcast.

Ted Muldoon is a senior producer and sound designer for The Washington Post. He joined The Post in 2017. Besides his work on podcasts, he also sound designs for video and VR experiences. He won a Peabody in 2021 for his work on the audio documentary “The Life of George Floyd.” His work has been nominated for an Emmy and played at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Rennie Svirnovskiy is a producer for Post Reports, The Washington Post’s flagship daily news podcast.