By Jon Lee Anderson

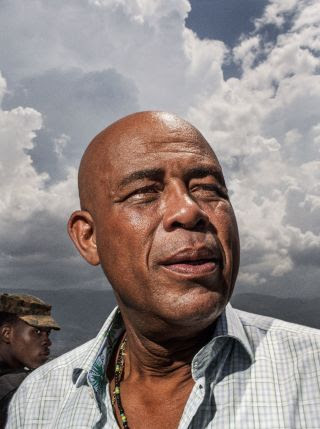

Before Michel Martelly was the President, he was Sweet Micky, a popular singer. Credit Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker A few months ago, a crowd of curious onlookers gathered on a newly built highway overpass in downtown Port-au-Prince. It was a humid afternoon, too hot to linger outside, but Haiti’s President, Michel Martelly, was scheduled to appear, and any appearance by Martelly was bound to be entertaining. Before being elected President, in 2011, Martelly was Sweet Micky, an extroverted singer of the ebullient dance music called konpa. A popular and bawdy showman, he appears in one typical video clip in a night club, dancing for the camera in a red bra and a yellow sarong. At one point, he feigns masturbating a giant phallus, then hoists an imaginary breast and licks it.

Before Michel Martelly was the President, he was Sweet Micky, a popular singer. Credit Photograph by Philip Montgomery for The New Yorker A few months ago, a crowd of curious onlookers gathered on a newly built highway overpass in downtown Port-au-Prince. It was a humid afternoon, too hot to linger outside, but Haiti’s President, Michel Martelly, was scheduled to appear, and any appearance by Martelly was bound to be entertaining. Before being elected President, in 2011, Martelly was Sweet Micky, an extroverted singer of the ebullient dance music called konpa. A popular and bawdy showman, he appears in one typical video clip in a night club, dancing for the camera in a red bra and a yellow sarong. At one point, he feigns masturbating a giant phallus, then hoists an imaginary breast and licks it.

At the overpass, jeeploads of riot police fanned out, and workmen set up a red carpet and a lectern with the Presidential seal on it. Martelly was coming to inaugurate the Delmas Viaduct, a four-lane bridge over a deep gully at the base of Delmas, a densely populated hillside neighborhood. As the crowd grew, a rara band, a squad of dreadlocked teen-agers, showed up to blow horns and beat drums. Martelly, who is fifty-four, arrived in a pink-and-white checked shirt worn untucked over black jeans. His shaved head gleaming, he cut a casually hip figure amid an entourage of plainclothes bodyguards and officials in suits. At the microphone, he spoke in guttural Creole, a French patois that is Haiti’s primary language. “This viaduct proves once again that together we can achieve great and beautiful things,” he said. “More than a dream, more than a project, this viaduct is now one of the symbols of Port-au-Prince.”

Martelly’s Presidency has been predicated on rebuilding. He took office a year after the January, 2010, earthquake that devastated Port-au-Prince, killing perhaps two hundred thousand people and leaving millions homeless. The disaster drew the world’s attention to Haiti’s long struggle—and, to some extent, offered a chance for a fresh start. In a survey of American voters, more than half reported donating to help repair the country; Bill Clinton, whose family foundation is deeply involved in Haiti, announced the hope that it could “build back better.” But Delmas, like much of Port-au-Prince, has been at best partly repaired. Even as the new overpass was unveiled, tens of thousands of residents were still displaced. As Martelly finishes his term in office, Haiti remains the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Some sixty per cent of its ten million citizens live in poverty. Nearly half are illiterate, and only one in four has access to a toilet.

On the road below the overpass, a stage had been set up. It was the final day of campaigning for forthcoming elections, and Martelly was throwing a concert to give one last push to his political organization, the Tèt Kale (Bald Head) Party. Several thousand young people had gathered before a police cordon, and for five hours, as bands came and left, Martelly served as the master of ceremonies. From the stage, he encouraged his officials to get loose and have a good time. The minister of public works, Jacques Rousseau, danced with increasing abandon; finally, in homage to his boss, he pulled down one side of his shirt to lick an imaginary breast. As the crowd warmed up, Martelly crouched on the edge of the stage, growling into the microphone. “You want me to take off my pants?” he said. “I know that’s why you’ve come. You want me to?” As people yelled “Oui!,” he laughed, turned his back, and gave an insouciant waggle.

It is not unusual for a politician to be a showman, but Martelly’s survival has depended on managing his audiences with exceptional adroitness. A member of the country’s light-skinned élite, he has been repeatedly accused of enriching himself in office. Opponents claim that he has consorted with kidnappers, murderers, and drug dealers, and that members of his family are corrupt. Martelly has blithely carried on, alternating between his Presidential duties and appearances as Sweet Micky. The United States has offered steady support, interrupted by an occasional scolding for his worst scandals.

In public, Martelly still urges his citizens to make Haiti a place of progress and prosperity—a message of self-reliance that is both an acknowledgment that the world has stopped caring and a defense of his administration’s failings. In Delmas, he told the audience, “All I ever hear is that Haiti is a dump, Haiti is corrupt, and Haitians can’t do anything for themselves. But we are doing some things for ourselves!” As the crowd shouted in agreement, he said, “Haiti is a country with a few rich people and a lot of others who live in the shit.” He pointed up toward the hills around town, where the wealthy live, and where his house is situated. “I could be with them,” he said. “But I am not. I am here, with the Haiti that lives in the shit.”

In “The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster,” the journalist Jonathan M. Katz writes, “It’s not that politicians in Haiti are more venal, petty or brutal than elsewhere; it’s just that, too often, that’s all there is to them.” Haiti’s political life has always been volatile. In 1971, François Duvalier, known as Papa Doc, died in office after fourteen years of brutal rule. His son, Jean-Claude, or Baby Doc, succeeded him; he was only nineteen, but parliament had accommodated him by lowering the minimum age for high office. In 1986, amid growing unrest, a popular uprising forced Baby Doc into exile. Haiti’s long dictatorship was over, but the following decades were plagued by repression, corruption, and political violence. In 1991, Jean-Bertrand Aristide—a charismatic priest from the slums with socialist leanings—became President, and his administration was twice interrupted by coups. The U.S. invaded in 1994, hoping to enforce stability, and ten years later the U.N. sent in peacekeeping troops.

After Secretary of State Hillary Clinton heard the news of the earthquake, she exclaimed, “Why Haiti?” An earthquake seemed like a gratuitous insult to a place that had already suffered so much. When I visited, in the immediate aftermath, there were foreigners at work everywhere: U.S. military planes flying in emergency supplies; U.N. peacekeepers patrolling in armored personnel carriers; teams from Israel, Cuba, France, and a dozen other countries, distributing food and providing medical care. At a clinic set up in a neighborhood school, I watched American doctors amputate groggy patients’ injured feet and hands, tossing them into plastic buckets. At the city’s main hospital, Bill Clinton strolled past the injured, smiling broadly, with the CNN doctor Sanjay Gupta at his side.

Yet all this well-intentioned activity barely diminished the tragedy. Victims lay trapped under rubble, and survivors walked wordlessly around the shattered capital, looking for food and water, or for help rescuing their loved ones or burying their dead. Prisoners who had escaped from the damaged National Penitentiary roamed the city center, and police executed suspected criminals in broad daylight. Less than a hundred yards from the gate of a primary U.N. depot, I saw the body of a man who had been tied to a pole and beaten to death for wandering into the wrong encampment of displaced people. As the country struggled to rebuild, cholera broke out, eventually infecting some seven hundred thousand Haitians. It was traced to a contingent of U.N. peacekeepers from Nepal. The Haitians themselves seemed more than ever reduced to passive onlookers. When I asked René Préval, the President at the time, about the response, he told me that the earthquake wasn’t his fault.

When Martelly decided to run for President, he was a political novice, but the earthquake provided an opportunity. The country’s institutions, and the international community on which they depended, had disappointed Haiti in every conceivable way. Martelly was a celebrity, whose music appealed to Haitians of all political viewpoints. And, as a pro-business populist, he represented a break from nearly two decades of leftist politics. Martelly had famously opposed Aristide; in one widely disseminated video, he pithily threatened to “kill Aristide and stick a dick up his ass.” He was an advocate of entrepreneurship, with a slogan, “Haiti Is Open for Business,” that seemed optimistic to the point of magical thinking.

The actor Sean Penn, who managed a camp in Port-au-Prince for Haitians displaced by the earthquake, told me about meeting Martelly during the campaign. One night, there was a shooting incident between Martelly’s followers and U.N. peacekeepers, and protests spilled into the streets. As the violence threatened to spread, Penn worried that it would interrupt shipments of medical supplies. Shortly before midnight, he went to see Martelly, driving through streets where angry young men stood at barricades, burning tires. “When we got to Martelly’s house, all of his advisers were there, and he was in a back room,” he said. “Then Martelly emerged, and he was very casual. I must have seemed like a white surfer dude from California, an actor boy who may or may not have been doing some good things for his country. I told him that he had to get his people to stand down, and he exploded. He shouted, ‘You motherfuckers! You think you’re doing so much. Well, this is democracy! Give me liberty or give me cholera!’ When he said that, I was pretty impressed.”

Haitian elections often proceed in two stages: a first round and then a runoff between the top two candidates. In the initial round, Martelly came in third, behind Jude Célestin, Préval’s favored successor. Martelly charged fraud, and thousands of his followers swarmed the streets. The Organization of American States, which was monitoring the vote, held a partial recount, and determined that Martelly had come in second. (The O.A.S. diplomat who oversaw the recount, Colin Granderson, told me that a huge number of votes cast for Célestin turned out to be fraudulent.) In January, 2011, Hillary Clinton flew to Port-au-Prince to underscore the U.S. government’s support for the decision. In the runoff, Martelly won the Presidency, with sixty-seven per cent of the vote. However he had won, it seemed clear to most people in Haiti that Martelly was the man the Americans wanted.

When I returned to Port-au-Prince recently, the streets were mostly clear of rubble, but some of it was merely hidden behind construction barriers. There was a new police headquarters and a new Supreme Court building, and the tents were gone from the public parks; thousands of displaced people had been forcibly removed and left to fend for themselves. Yet the downtown remained battered. Once a grand commercial district with colonnaded streets, it is now a motley open-air market, where venders set up stalls amid cracked, precarious buildings.

The Presidential palace collapsed in the earthquake, so Martelly keeps his office in the former security headquarters: a white, two-story complex where, decades ago, Papa Doc’s thugs tortured people. One morning, Martelly met me there, wearing black slacks and a sharp yellow guayabera with large black buttons. His aides had set up an impromptu television studio—a camera and a Haitian flag as a backdrop—but Martelly waved dismissively at it and said, “Don’t worry about all this, man. Ask me anything; I’ll answer any questions you have.”

Martelly’s bluntness has been a signature. In public, he often urges Haitians to take charge of their own destiny, in a way that can evoke Bill Cosby in his patrician pre-scandal guise. “When I drive to work, I see young guys drinking beer and smoking joints on the street,” he chided the audience at Delmas. “Is that any way to fix the country?” In his office, he told me, “The fact that sixty to seventy per cent of Haitians don’t read isn’t the fault of the Americans or the Chinese. It’s our own bad governance.”

In Martelly’s view, it was this kind of uncensored talk, not any wrongdoing, that fed the allegations his opponents made. At a political rally a few weeks before my visit, a woman had heckled him about the government’s inability to provide her neighborhood with regular electricity. Martelly fired back in Creole, calling her a “whore” and saying, “If you want to fuck, grab any big dude in the crowd and go over the wall. If it’s me you want, I’ll do it with you right here on the podium.” When other Haitian politicians voiced disapproval, a senior Martelly aide claimed that the comment, although recorded and widely rebroadcast, had been doctored. Furthermore, the President had said not “whore” (bouzen) but “cousin” (kouzen). A couple of days later, three cabinet members, including the minister of women’s affairs, resigned in protest.

Martelly told me, “Sometimes I say something crazy to say something good. For instance, a woman might come to me and say, ‘I have eight kids, and I want help.’ I say to her, ‘Why are you coming to me? The state didn’t sleep with you!’ And the word I use might be a little . . .” Martelly made a risqué expression. “But it’s serious, too!”

He insisted that he had a uniquely Haitian way of doing things. “My style is my style, and people try to criticize me for it, but I don’t mind,” he said. “As a matter of fact, that’s probably why people voted for me. And that’s why, at the end of my term, I am probably the only person in the country who people fight to come and see.”

When I asked what his achievements were, he looked momentarily at a loss, then ventured, “Definitely education—free education for all. And also removing people from the tents. People were living freely, having kids, not paying for electricity. We put a stop to that.” The education program, like much else in Martelly’s term, has been controversial. He funded it with hundreds of millions of dollars raised from Haiti’s diaspora, by levying a small tax on money transfers and international phone calls. Some critics allege mismanagement and corruption; others argue that the scheme has mostly benefitted the private sector, which runs eighty per cent of Haiti’s schools. Martelly acknowledges the problems, but points out that attendance has increased, especially among preschoolers.

His claims to self-determination have a special appeal in Haiti, where many normal governmental functions are handled by N.G.O.s funded from abroad, leaving officials with little agency. The country has also endured a long-running military intervention that is unique in the Americas. In the nineties, Aristide, with U.S. encouragement, disbanded Haiti’s Army, known as a corrupt agent of political repression; it was effectively replaced by the U.N. troops who arrived in 2004, and who are still patrolling the streets. Martelly has long insisted that reviving the Army would provide jobs and reinforce sovereignty. “With one-tenth of what the U.N. spends, we could have a Haitian Defense Force,” he said. “If they had brought that money to bring jobs to Haiti, maybe we’d have the same amount of stability we have now, and probably be more sustainable.” The long recovery effort was similarly compromised, he complained: of thirteen billion dollars promised by international donors, “we got less than four billion, and it came with all kinds of conditions.”

Martelly’s arguments were those of a leader who had discovered severe limitations on his authority. When I asked how much power he actually wielded, compared with the foreign presence in Haiti, he gave a sour smile and said, “I’ll tell you one thing. It’s definitely not fifty-one per cent.”

When Martelly took office, parliament was working out of ramshackle temporary quarters, in a police academy on the outskirts of the capital. The government was in disarray: some thirty per cent of civil servants had died in the earthquake. And though huge amounts of money had been promised, the country was effectively broke. Martelly’s cousin Richard Morse—the owner of the Hotel Oloffson, made legendary in Graham Greene’s novel “The Comedians”—recalled those days as hopeful ones. “The left had failed, the right had failed, we’d had the earthquake—and so this was supposed to be about trying to figure out something else,” he explained. “But, as soon as he knew he’d won, it changed.”

Martelly has shaped his government largely on the basis of instinct and personal affinity, hiring and firing numerous cabinet ministers, drawn from Aristide’s former party and, more often, from among his friends. Hilda Baker, a political consultant who worked closely with Martelly’s Interior Ministry for a year, said, “They didn’t know how to govern, and weren’t very nice to the entrenched bureaucracy.”

Martelly’s rivals in parliament refused to pass the laws that he proposed, and for years he argued with them over the makeup of an electoral commission, without which no elections could be held. As the government slowed to a halt, Martelly realized that he had an advantage: when members of parliament reached the end of their terms, the impasse would make it impossible to elect successors. In 2012, a hundred and thirty elected mayors had their terms expire, and he replaced them with government appointees. By last spring, only eleven elected officials remained in Haiti, and Martelly’s opponents were furiously attacking him for ruling by decree.

These days, Port-au-Prince buzzes with accusations about the President. Alice Blanchet, who has been an adviser to several prime ministers, spoke of Martelly as a “thief” who had “no regard for the law.” Former officials accuse him of using molly, cocaine, crack. Martelly’s history makes him susceptible to such rumors; he built a career providing music for unrestrained partying, and he has admitted to smoking crack in earlier days. Yet nearly all these allegations are made without any evidence, by political opponents who seem to rely more on theatrical flair than on facts. One businessman who joined Martelly’s government after the earthquake told me that he resigned when he saw “dark forces taking over.” When I asked him what he meant, he demurred: “I could get a bullet in the head.”

The more substantial charges are about those who surround Martelly. When I asked the businessman whether the President was corrupt, he said, “Nothing in my presence pointed to personal corruption. Among some ministers, yes.” Baker told me that, during her time at the Interior Ministry, she was encouraged to add ten per cent to each contract to allow for graft. “The problem is that the people who follow Michel are gangsters,” she said. “It is a gang government.” She now works with a rival political party, and periodically visits the slums to meet with gang leaders and pay for their loyalty. She said they had told her that they also took payments from Martelly’s people.

Last month, a U.S. congressional assessment of Martelly’s government gave him the benefit of the doubt: “Although corruption is a widespread problem, the State Department reports that the government does not encourage or facilitate distribution of illicit drugs or the laundering of drug-trafficking profits.” But several of Martelly’s close associates have been accused of serious crimes. In 2013, a friend and political supporter of his was arrested on drug charges. Soon afterward, the prosecutor who ordered the arrest, Jean Marie Salomon, was suspended for abuse of power. Salomon quickly resigned and left the country; the friend disappeared. In another case, Woodley Ethéart, a former music promoter, was charged with leading a gang that was suspected of kidnapping seventeen people and killing a police inspector. The judge in the case found that Ethéart had made several calls to the kidnappers, and noted apparent financial irregularities: Ethéart, an employee of the Interior Ministry with a salary of about fifteen hundred dollars a month, had six cars and seven bank accounts. (Ethéart denied any wrongdoing.) His family also ran a lavish French restaurant where the President dined frequently. After Martelly’s brother-in-law, a friend of Ethéart’s, called officials on his behalf, the prosecution dropped the charges, arguing that no evidence linked him to the gang.

Pierre Esperance, who runs Haiti’s National Human Rights Defense Network, expressed frustrations when I visited his office, in Port-au-Prince. “There are a lot of people around Martelly and his family who have connections with criminal gangs,” he said. Martelly’s wife, Sophia, has often been accused of profiting from a term as the head of a Presidential commission on alleviating poverty; her brother Kiko has admitted selling drugs in the past, and he allegedly remains involved in narcotics trafficking.

When I talked with Sophia Martelly, she pointed out that her husband’s administration had been unusually lenient with the press and with political opponents, and suggested that the unconstrained atmosphere encouraged speculation. The commission she led lasted a year and spent less than a million dollars, she said: “Even so, the opposition came and accused me of stealing thirty million dollars from it.” She threw up her hands and looked incredulous. “With Michel, it’s the first time Haiti’s press can do whatever they want,” she said. “They can call me a slut, anything they want.” When I asked about the accusations against her brother, Sophia fell silent. Finally, she said, “My brother is my brother. I love him, and he will always remain my brother, no matter what.”

One of Martelly’s former advisers describes him as a “boiling man”: eager to get things done but distractible. The landscape in and around Port-au-Prince provides a record of his fitful accomplishments. Throughout his Presidency, Martelly has lobbied heavily for international investment in Haitian tourism. With the country’s poor infrastructure and alarming crime rates, it was initially a hard sell. Since Martelly took office, airlines have opened new routes to Haiti, and revenue from tourism has quintupled. The State Department continues to warn prospective travellers to buy evacuation insurance. But, as Martelly told me, “gun crime is down, and almost no one gets kidnapped anymore!”

On the skyline, a handful of striking new buildings suggest the glimmerings of a business revival: a Marriott hotel, a Best Western Premier, a Royal Oasis, and an office tower for the cell-phone provider Digicel. “We’ve been able to create confidence,” Martelly said. Since 2012, the economy has grown three to four per cent a year.

But much of that growth has been spurred by aid money. The earthquake brought pledges of support from around the world, estimated at more than thirteen billion dollars. Of that, humanitarian relief money amounted to almost two and a half billion dollars—but, as Jonathan Katz notes, “at least 93 percent would go right back to the UN or NGOs to pay for supplies and personnel, or never leave the donor states.” Only six hundred and fifty million dollars reached the Haitian government, and it came with severe restrictions.

One afternoon, I met Yves Germain Joseph, the planning minister, who is charged with handling public works. A no-nonsense economist in his sixties, Joseph has worked in government since the Duvalier days, and formerly served Martelly as a senior adviser. In his office, in a modest villa on a hillside in Pétionville, Joseph told me that, in many of the projects supported by the U.S. and its allies in the international community, Haiti had little agency. He described an eighty-million-dollar effort to rebuild the country’s main university hospital. “The donors gave the bid to a Spanish firm, and although the Haitian government gave a third of the money, it doesn’t have enough authority to affect the outcome,” he said. The project became mired in international disagreements, and construction never got started.

Money from elsewhere in the world has come with fewer stipulations. Joseph showed me an album of photographs illustrating government projects: page after page of schools in rural areas. Virtually all had been financed by funds from Petrocaribe, an oil program created by the late Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chávez. Martelly reportedly received about two hundred million dollars a year from Petrocaribe, to spend as his government saw fit. Some of the projects have become embroiled in scandal: in one case, a journalist in the Dominican Republic produced documents suggesting that Martelly had taken two and a half million dollars in kickbacks for awarding contracts worth three hundred and eighty-five million dollars to companies owned by a Dominican politician. (Martelly said that the allegations were “all lies.”)

But the unmonitored funds had made possible most of Martelly’s recent public works, including the Delmas Viaduct. “The Petrocaribe money allows the government to establish its own priorities,” Joseph said. “The freedom given to the government in spending this money can allow for certain abuses, O.K. But between those abuses and the difficulties of obtaining these funds from the multilateral organizations, the benefits are obvious.”

Many Haitians feel that the problems are systemic. Maryse Penette-Kedar, the widely respected president of Prodev, a foundation that provides education for underprivileged children, told me, “If another guy had been President, and the institutions were this weak, it would be the same now, with corruption and this and that.” Penette-Kedar has lived in Pétionville since 1953, in one of the district’s oldest remaining houses. “We’re worse off than we were then,” she said. “We don’t even have one bucket for every Haitian to take a bath in every day. This is the most fucked-up situation in the Western Hemisphere, and I think everyone needs to take a pause and assess.” Penette-Kedar didn’t blame Martelly. “He has done things that others didn’t do, and I think he will never say no to something that will help this country,” she said. “But the problem is follow-up, a team to manage what he’s done. I think he’ll be shocked in a year to hear stories about certain things that happened that he was not even aware of.”

At times, Martelly seems as regretful as anyone else. “I had a big learning curve,” he told me. “I am disappointed, because by the time I figured it out I was too far into my mandate to make big decisions.” The flow of aid is slowing, and he doesn’t have much time to complete his initiatives.

One morning, he took me to see one of his projects, in Wharf Jérémie, a crime-ridden slum on the bay in Port-au-Prince. As we arrived, a crowd of young men and boys greeted him, waving and shouting to get his attention. Martelly strode through the crowd, tossing out cheap soccer balls from a plastic bag; when scuffles broke out over them, he sent his security men to intervene. Next to the bay, hundreds of people milled around a construction site. The engineers overseeing the project explained that, after two years, their team had nearly completed a covered market, a pier and a jetty for a handful of fishing boats, and a pair of vocational schools. In the distance, across the bay, a vast mosaic of shanties spread across the hills. Martelly looked around. “It’s not much,” he said, with rough candor. “These people have always lived in the shit, and, even with this project, they’re still going to be living in the shit. But it’s something.”

Haitians who are dismayed by their country’s progress increasingly blame the developed world. Esperance, the human-rights leader, told me, “If you go to the U.S. Embassy and complain about Martelly, they tell you, ‘Aw, it’s just Haiti, the institutions are weak.’ ” He added, “The fact is, the international community supports all of Martelly’s transgressions.” Though the U.S. cut off aid to Haiti for three years under Aristide, it has kept sending money to Martelly—some three hundred million dollars in 2014.

For most of Martelly’s term, the U.S. Ambassador to Haiti was Pam White, a close friend of the Clintons who was appointed in 2012. White had a background in international aid—including five years in Haiti and stints as a U.S.A.I.D. director in several African countries—but only two years of diplomatic experience. Even as allegations increased against Martelly, she maintained such close contact with him that she was referred to in Port-au-Prince as “Haiti’s second First Lady.”

White left her post in September, and retired to an island in Maine. When we spoke recently, she praised Martelly warmly. “I think the country grew under his leadership,” she said. “And it’s pretty amazing that he managed to survive five years, too—Haiti has a way of getting rid of its leaders before their time is up.” In her telling, he had reshaped the country’s infrastructure: “They built something like two hundred schools, several hospitals, kilometres and kilometres of roads, water reservoirs.” She acknowledged that a lot of the projects were paid for with Petrocaribe money, and that several ministry buildings hadn’t been finished. She wasn’t sure where the money had gone: “It’s a valid question.” But she defended the efforts of the international community. “There were ten million cubic feet of rubble! And most of the work of removing it was being done by wheelbarrow. In 2012, there were still three hundred and fifty thousand people living in tents; now it’s down to sixty-five thousand.”

In important areas, White agreed, Martelly had made little headway. “The judicial sector is still a complete mess, corrupt from top to bottom,” she said. But, asked about the allegations against him and his associates, she said that she had tried to investigate but got nowhere. “I kept hearing the rumors and kept asking my people, ‘Show me something,’ ” she said. “And I’ve got to tell you—no one put so much as a piece of paper on my desk.”

Many close observers are perplexed by America’s policy in Haiti. Vicki Huddleston, a former chargé d’affaires at the U.S. Embassy and a friend of White’s, said, “I always wanted to ask her, ‘Why are you so close to Martelly?’ ” A longstanding D.E.A. informant in Haiti suggested that, even if the allegations about his associates were true, no one was particularly concerned. “The President may have used his influence to give someone a get-out-of-jail-free card—but, well, this is Haiti,” he said. And, whatever else Martelly had done, he complied with the D.E.A.’s local operations, which resulted in several major busts, including a recent one in which two nephews of Venezuela’s First Lady were arrested for trafficking cocaine.

Perhaps the most common and persuasive theory is apathy and distraction. Katz told me, “Obama and Clinton’s political legacy in Haiti is a bad-boy former pop star from the militarist right who took until the tail end of his term to hold an election. I think he’s probably achieved more or less what they wanted him to: he stayed in power, didn’t kick out the U.N., didn’t stand in the way of foreign-investment projects, and resisted political violence, just enough to keep the country from melting down. The fact that nearly everyone in Haiti is worse off than they were five years ago gets a pass. That’s the tyranny of low expectations for you.”

A Western official in Haiti suggested that the goal was containment. Tens of thousands of “boat people” have fled Haiti since the seventies, and many have ended up in the U.S. “The bottom line for the Western democracies is that we don’t want chaos in Haiti,” the official said. “If that happens, we’ll have three million Haitians trying to find a blade of grass to eat somewhere else.”

Pam White seemed wary of forming conclusions about Martelly’s ethics. When I asked about the allegations that he had covered for his friends, she said only, “You know, he had a career for thirty years where these people were his friends.” White told me that she and Martelly had talked at times about the disposition of government contracts. “He used to say to me, ‘I never made a cent off of this,’ ” she said. She laughed, and added, “But, then again, why would he tell the truth?” Even after decades, the place seemed impenetrable. “In the end, I only ever trusted five people in Haiti,” she told me. “I have known people there for thirty-five years, and, you know, they’ll lie right to your face.”

One afternoon, I asked Martelly what he was going to do when he left the Presidency: Go back on the stage? Go into business? “I want to do it all,” he said. “But the first thing I want to do is—when I leave office, it’ll be the same day as Carnival in Haiti. I’m thinking I am going to go straight away and get on a Carnival float. I want to boom it out.”

His real plans seem much more tightly directed. Although Haitian law forbids Presidents to hold consecutive terms, they are permitted to run again after a five-year break, and Martelly clearly intends to hold on to his influence. When I asked him about leaving office with so much left undone, he said, “If there is continuity, I can come back.”

At the concert in Delmas, he introduced a paisan who grew bananas, and who had just signed a contract to sell a hundred and fifty million euros’ worth to Germany. He turned to the line of aides standing behind him and beckoned to a slender man to come forward. “This is the man I have picked to succeed me for my party,” he said. “His name is Jovenel Moïse.” As the crowd roared, Martelly said, “He looks too skinny to be a politician, I know!” Appearing grateful, Moïse stepped up to speak for a moment, and then stepped back. The crowd applauded dutifully, and the music resumed.

For many in the country, the results of the elections are a foregone conclusion. Georges Michel, an eminent historian who has advised Martelly on restoring Haiti’s military, told me, “Martelly is so popular among the lower classes, who dance to him, that he could propose a dog to be elected, and they would vote for it.” The first round of elections was held in October; Moïse, campaigning as the Banana Man, was the front-runner, with thirty-three per cent of the vote. Jude Célestin, who lost out to Martelly in 2011, came in second, and quickly protested that the process was unfair: Haiti’s electoral commission found problems with eighty per cent of the ballots. As the runoff was postponed, until late January, Célestin argued that it should be cancelled and an interim government formed. But the Western official told me, “We are funding these elections, and, frankly, we are not going to allow that. If Célestin doesn’t want to compete, then the other man is going to win.”

Moïse’s plantation sits near the coast, in a place called Trou-du-Nord—Hole of the North. One morning, I met him there, in a town-size square of vividly green banana trees fringed by mountains. Moïse was talking jovially with workers as they loaded freshly cut banana stems onto a truck. One said, teasingly, “Mr. President, you’re leaving us behind, Papa.” Moïse laughed, and denied that he would ever leave.

He was being shadowed by a German man, a quality-control inspector from Fruit Logistics, the company that had signed the export agreement with him. With an Eagle Scout’s enthusiasm, Moïse explained that his plantation had twenty-five hundred acres planted in bananas; it would eventually expand to fifteen thousand acres. There were three thousand workers, who belonged to a coöperative that held equity in the business. In a week, he would send off a shipment—Haiti’s first export of bananas in sixty years. “We used to be the No. 1 banana exporter in the Caribbean, and after 1955—nothing,” he said.

Moïse had trained as a water-treatment engineer, but he became convinced that the coastal plain was exceptionally fertile, and had drawn up plans for a plantation. He had met with Martelly early in his term and asked him for support. At first, Martelly resisted, telling him that he was “crazy,” but he was eventually won over. The two joined an agricultural delegation to Europe, where Moïse, at a conference of fruit importers, secured the Germans’ interest.

The President’s backing had been crucial, he said: “Without political power, this country can’t be developed.” With that in mind, he had decided last spring to run for parliament. Martelly dissuaded him, saying that there were two other candidates vying for the seat. He had a better idea: “I think you can be the next President.” Martelly told him that he would back him if he agreed to run.

“I talked to my wife,” Moïse recalled, laughing. “She said to me, ‘You have to run. You are like Messi or Jesus Christ. It’s your job to save Haiti.’ ” Moïse offered a brisk plan, strikingly like Martelly’s, to save the country: “Agriculture, tourism, construction, business, outsourcing. We have seventy-five thousand government employees who give only ten per cent of their work capacity. We will try and get them to thirty per cent. We have the people and the knowledge—it’s the mentality we lack.” He seemed enlivened by campaigning. “It’s exciting, because I like my country, and I am a winner,” he said. “I am going to win!” I asked if he and Martelly had a twenty-year plan in mind, trading places in the Presidency. Moïse nodded. “Yes. It’s a good plan. We need stability. We need it.” ♦