Henry urges people to remain calm while his government is replaced by a transitional council.

By Peter Beaumont and Luke Taylor in Bogotá, The Guardian —

The embattled Haitian prime minister, Ariel Henry, has resigned after a gang insurrection against his government plunged the country into anarchy and prevented his return from a trip to Kenya.

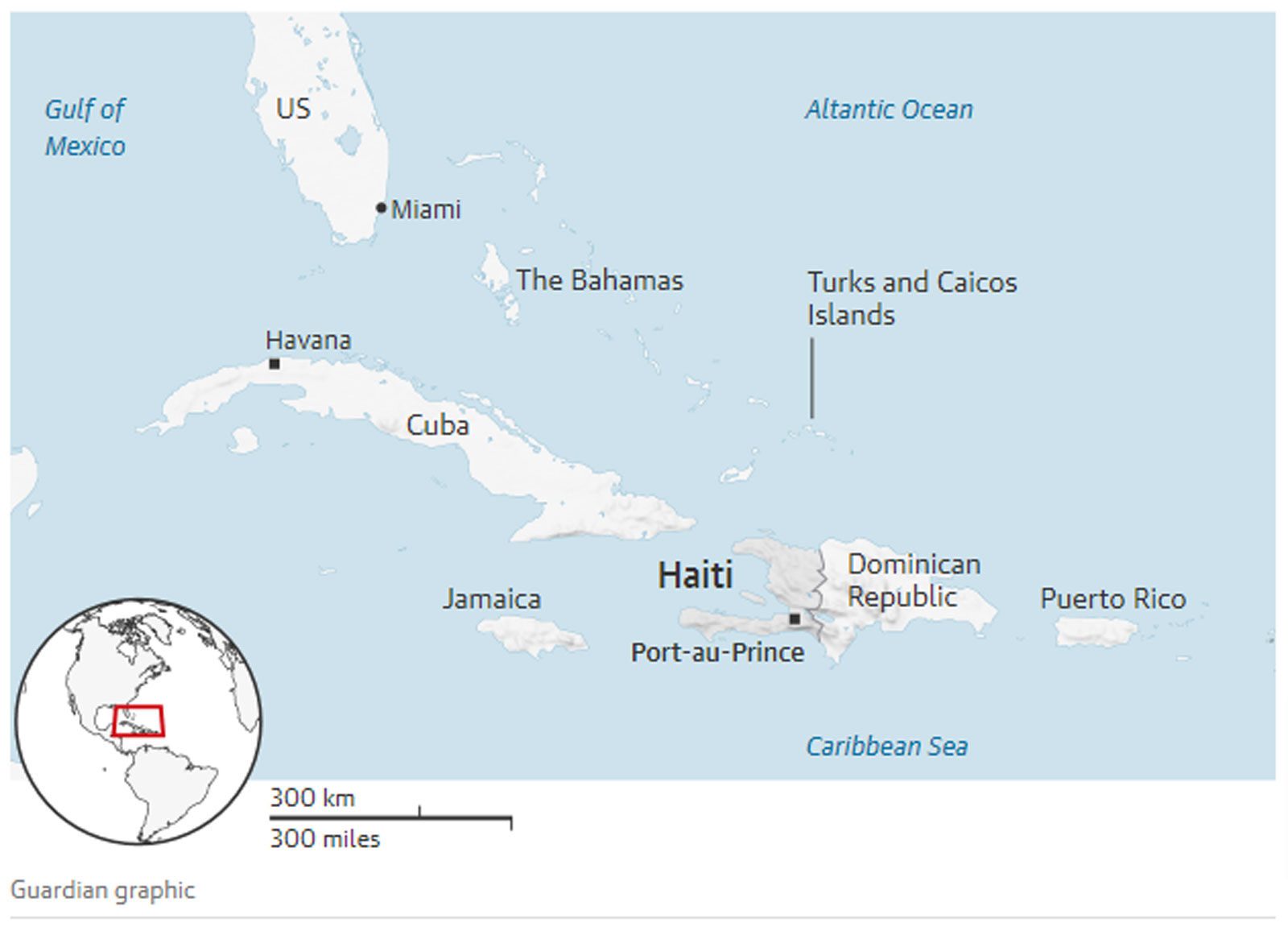

Henry, who is now in Puerto Rico, said he would formally quit after the installation of a transitional council to lead the Caribbean state, which has been submerged in chaos since the assassination of its president Jovenel Moïses in July 2021 by Colombian mercenaries.

“For more than a week, our country has experienced an increase in acts of violence of all kinds perpetrated against the population: assassinations, attacks against law enforcement, looting, systematic destruction of public and private buildings,” Henry said in the video statement.

“We deplore the numerous losses of human life. The government that I lead cannot remain indifferent to this situation. As I have always said, no sacrifice is too great for our common homeland Haiti.

“I’m asking all Haitians to remain calm and do everything they can for peace and stability to come back as fast as possible.”

Haitian leaders meeting in Jamaica have agreed to form a new transitional government led by a seven-member presidential council that will choose a new interim prime minister, but it is unclear who will lead Haiti out of the crisis that has involved a wholesale collapse of democratic accountability in a country that last had elections in 2016.

Henry had been trying to secure a UN-backed taskforce of foreign troops to bolster the country’s police and shore up order since October 2022. On 1 March, he finally got Kenya to sign an agreement to send 1,000 officers to the Caribbean.

Henry had been trying to secure a UN-backed taskforce of foreign troops to bolster the country’s police and shore up order since October 2022. On 1 March, he finally got Kenya to sign an agreement to send 1,000 officers to the Caribbean.

But further complicating the picture, Kenyan officials said on Tuesday that the deployment would be put on hold until a new government was announced.

“The deal they signed with the president still stands, although the deployment will not happen now because definitely we will require a sitting government to also collaborate with,” Salim Swaleh, a spokesperson for Kenya’s foreign ministry, told the New York Times. “Because you don’t just deploy police to go on the Port-au-Prince streets without a sitting administration.”

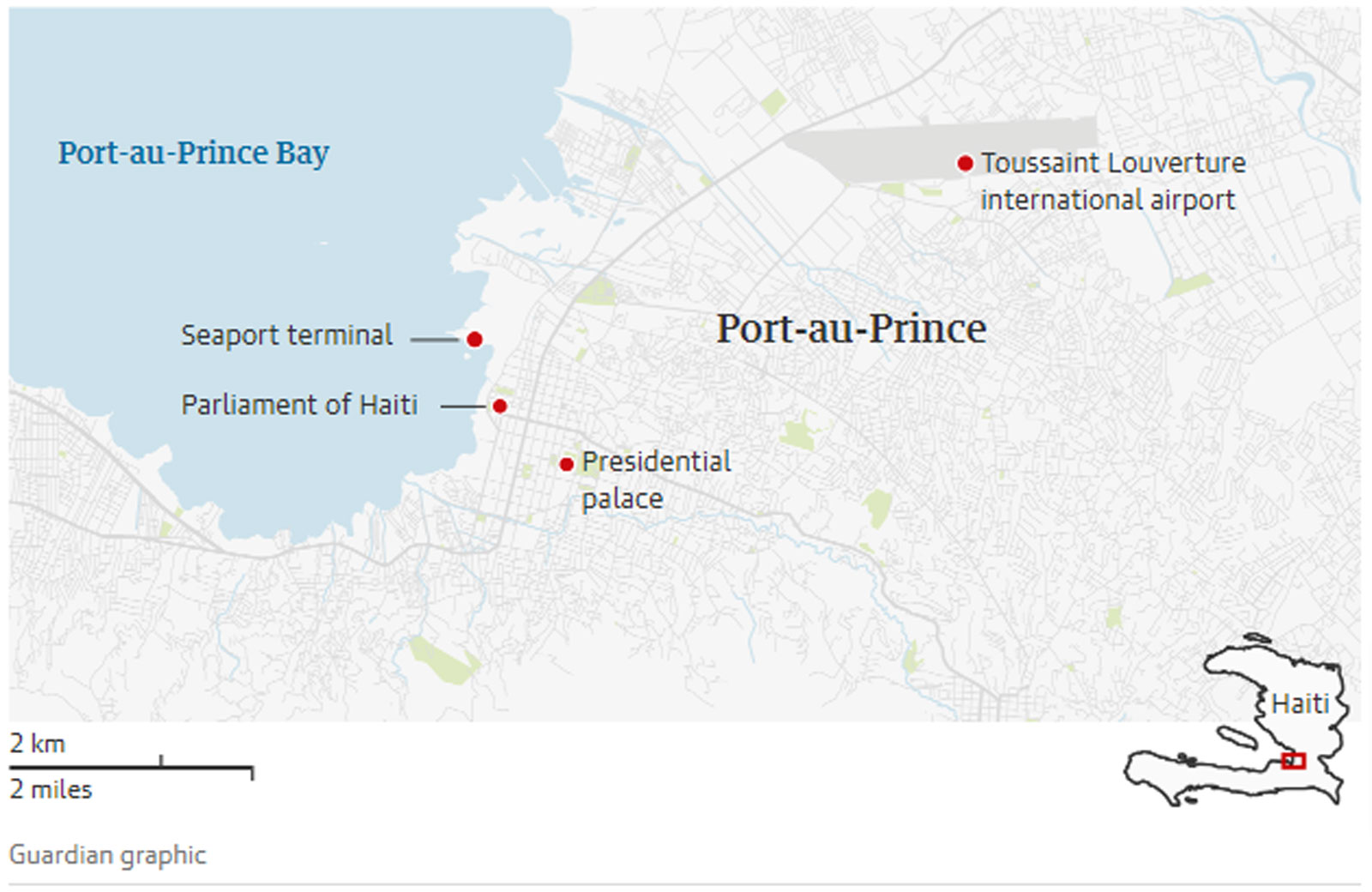

It is unclear how Haiti’s gangs – who now control 80% of the capital, Port-au-Prince – can be persuaded to disarm. “Even if you have a different kind of government, the reality is that you need to talk to the gangs,” said Robert Fatton, a Haitian politics expert at the University of Virginia. “You can’t suppress them.”

Fatton said officials would still have to deal with the gangs and try to convince them to give up their weapons, “but what would be their concessions?”

Underlining that point, Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier, a former police officer who is considered to be Haiti’s most powerful gang leader, told reporters that if the international community continued backing a transition, “it will plunge Haiti into further chaos”.

“We Haitians have to decide who is going to be the head of the country and what model of government we want,” said Chérizier, who leads the gang federation G9 Family and Allies. “We are also going to figure out how to get Haiti out of the misery it’s in now.”

Haiti’s gangs joined forces during 10 days of chaos during which they set police stations on fire, stormed ports and prisons and laid siege to the capital’s international airport.

Henry, who has been unable to enter Haiti because the violence has forced the closure of its main international airports, arrived in Puerto Rico a week ago, after being barred from landing in the Dominican Republic, where officials said that he lacked a required flight plan.

A senior US official said Henry remained in Puerto Rico, and that the decision for him to step down was made on Friday. Henry expressed a desire to return to Haiti in the future, the official said.

Henry’s resignation, however, seems unlikely to solve Haiti’s decades-long crisis of governance – punctuated by violence, natural disasters and external interventions, including by the US and UN – which has persisted since the Duvalier dictatorship was ended by an uprising in 1986.

Succumbing to a process set in motion by Moïses’s murder during a night-time assault on his Pétion-Ville home, Haiti’s enfeebled government has collapsed under the weight of gang and vigilant violence, some of it linked to political figures.

Succumbing to a process set in motion by Moïses’s murder during a night-time assault on his Pétion-Ville home, Haiti’s enfeebled government has collapsed under the weight of gang and vigilant violence, some of it linked to political figures.

The poorest country in the western hemisphere, Haiti has also struggled with widespread corruption among its political and business elite, as gangs – often more heavily armed than the country’s ineffective police – have turned vast areas into no-go zones, setting up check points to control roads and neighbourhoods.

Henry’s government was widely viewed as corrupt and illegitimate because it repeatedly failed to hold elections.

Videos distributed on Haitian social media appeared to show celebrations in the street, with people dancing to music in a party atmosphere while fireworks were launched.

Under the 74-year-old’s rule, gangs seized control of much of the country and regularly terrorised civilians, cutting off food and fuel supplies and blocking roads. Nearly half of the population – 4.35 million – regularly go hungry.

Among those with voting rights on the new council are the Pitit Desalin party, run by the former senator and presidential candidate Moïse Jean-Charles, who is now an ally of Guy Philippe, a former rebel leader who led a successful 2004 coup and was recently released from a US prison after pleading guilty to money laundering.

Source: The Guardian

Featured image: Haiti PM Ariel Henry