For too long, we have looked in the wrong place and race for the genesis of our national story.

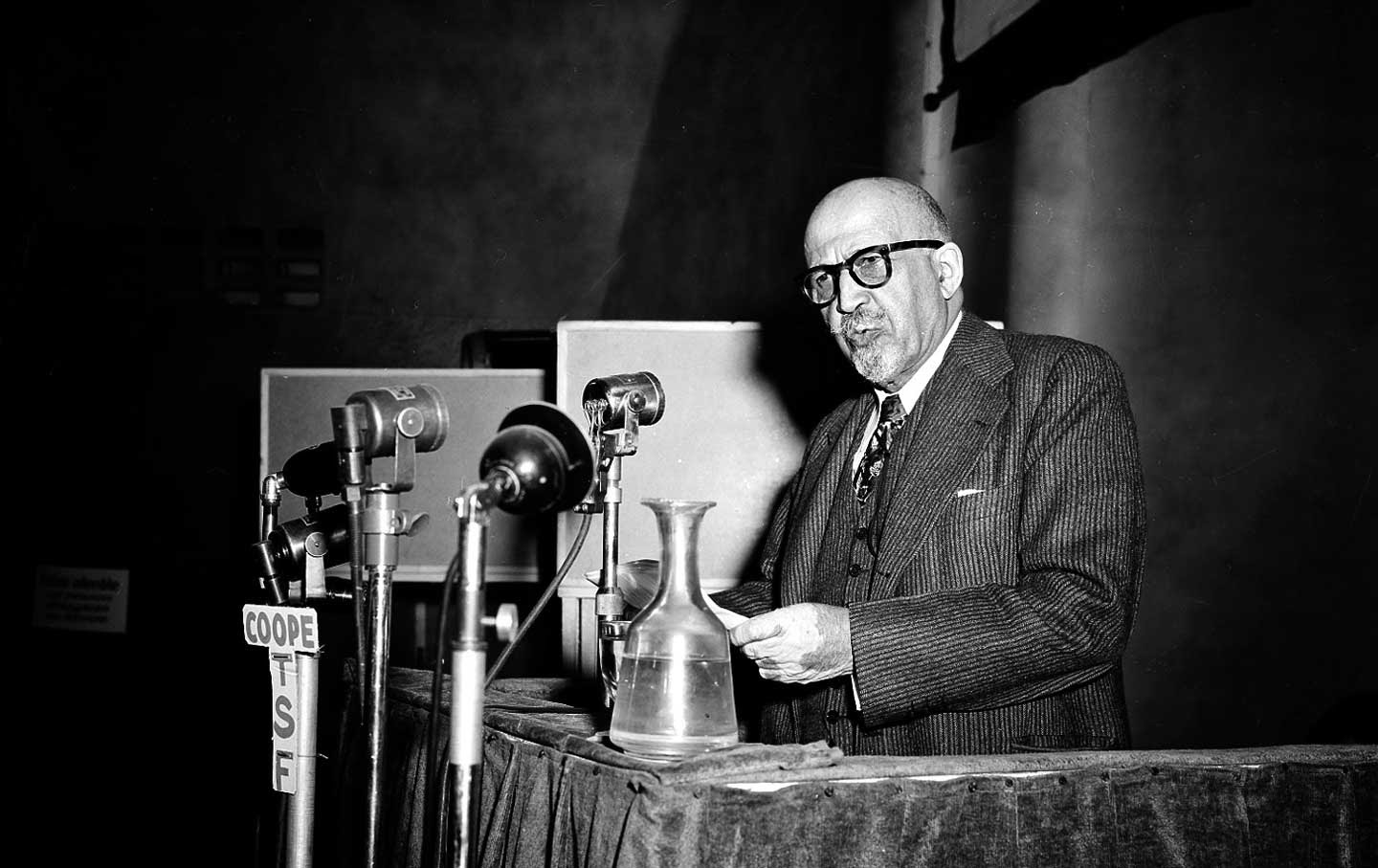

Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, educator, writer and co-chairman of the U.S. delegation, addresses the World Congress of Partisans of Peace in Paris, France, April 22, 1949. (AP Photo)

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an adapted and abridged version of the remarks delivered in May by David Levering Lewis upon receiving this year’s Arthur Meier Schlesinger, Jr., Distinguished Service Award from the Society of American Historians.

I find myself these days on the cusp of despairing over the cruel mischief long wrought by the paradigm known as “American exceptionalism.” I ask myself, why should I not conclude that what has been exceptional about our exceptionalist national narrative are the historic exceptions to it—notably, people of color?

Down the long corridor of interrupted progress from slavery to freedom, Africans in America have been unique victims and unimpeachable critics of a nation corrupted at its inception by a political economy anchored to race. Manumitted by war, politically empowered under Reconstruction, betrayed, disenfranchised, and re-subjugated during the 50-year nadir of Plessy v. Ferguson, African-Americans emerged from World War II a national people, urbanized, GI Bill–literate, occupationally diverse, but a people still forced and favored by history to pursue the role of redeemers of their nation’s founding egalitarian dogma.

Their great era began with the 1960s. If ever a time of epic breakthrough belonged to a single people, the racial, abortion, gender, immigration, gay, and handicapped rights channeled from the 1960s and ’70s were black people’s gifts to the nation. Even so, yet another great American deception for people of color was already in the making, as C. Vann Woodward and John Hope Franklin famously forecast: a Second Reconstruction that ended, like the first, with hard-won social and economic progress undermined and reversed by a triumphant Reaganism determined to nullify what survived of the New Deal, until most Americans finally recoiled from the consequences of their own electoral folly.

Against a bleak backdrop of indebtedness, unemployment, and rapid decline in traditional jobs, along with the non-affordability of the essentials of health and education, 53 percent of the electorate wagered in 2008 that it could deny race by affirming its non-importance and thereby audaciously reinvigorate the exceptionalist narrative.

As the Obama presidency ends, with much to its credit, the vision of a postracial reset that defined its historic debut seems belied by worsening disparities that are almost irrevocably color-coded, by Supreme Court majorities disingenuously mocking African-American and Latino voting rights, by a reborn nativism more virulent than its mid-nineteenth-century parent, and by criminal-justice-system irregularities perceived as outrageous enough to spark corrective uprisings from Ferguson to Staten Island to Baltimore.

It is certain that when this decade ends, it will have confirmed W.E.B. Du Bois’s grim prophecy about America’s everlasting racism. Can historians help, and if so, then how do we answer the Chernyshevskian question—what is to be done? In Black Is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy, New York University historian Nikhil Pal Singh asks, “What if the political lesson of the long civil rights era is that we advance equality only by continually passing through a politics of race and by refusing the notion of a definitive ‘beyond’ race?”

Moderately good news are those definite signs of a historical revisionism that upends the hoary master narrative of Herrenvolk democracy, its Jeffersonian laissez-faire matched with Hamiltonian finance, its unrivaled industrial takeoff, its robust middle classes gloriously replenished by hardworking immigrants, its eschatology of white merit.

For too long, we have looked in the wrong place and race for the genesis of the American story, as Craig Steven Wilder’s rum-and-sugar archaeology of the Ivy League (Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities) documents; as Parkman laureate Danielle Allen’s troubling parsing of the Declaration of Independence (Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality) suggests; or as Walter Johnson’s grim, close look at capitalism and slavery in the trans-Mississippi (River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom, Mr. Jefferson’s soi-disant “empire of liberty”) reveals.

Sven Beckert’s Bancroft Prize monograph, Empire of Cotton, brings things into sharper focus, because cotton, as he rightly says, is “the story of the making and remaking of global capitalism and with it of the modern world.”

With Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, we may have arrived by way of Eric Williams, David Brion Davis, James Oakes, and others of the profession’s vanguard at the frontier of a new meta-narrative that upends exceptionalism. If that proves accurate, we will comprehend how the institution of American slavery functioned as a vast, efficient concentration camp, from which flowed the enormous wealth that made the industrial North possible and the surplus capital upon which the commercial and industrial paramountcy of New York and Philadelphia were built. This is the dreadful reality of a vaunted national success story that is inconceivable without the constitutionally justified and enforced indispensability of 4 million black lives that mattered.