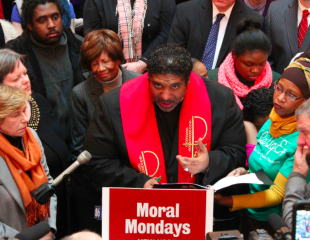

National movement: Rev. William Barber (center) speaks to media at a Moral Monday rally in Albany, New York, in 2015. (Courtesy of North Carolina NAACP)

After the Civil War, when the peace had been won and Reconstruction had begun, The Nation sent a writer through the South to report on the fledgling democracy. Both the heirs of William Lloyd Garrison and the new black citizens of Dixie understood that winning the South could mean a new America.

Fifty years ago, when the South stood in the throes of a Second Reconstruction, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. filed reports on the civil-rights movement for this publication. King sought not only to document the South as it was, but to envision the nation as it should be. “Throughout our history, the moral decision has always been the correct decision,” he insisted. And the struggle for that moral decision, King added, was being waged in the South.

Fifty years later, it is easy for progressives to write off the South. Whatever flag flies over them, statehouses across Dixie harbor extremists who have gerrymandered voting districts and, now freed from the Voting Rights Act, have launched a raft of new anti-voting legislation. To many liberals, these George Wallace look-alikes are precisely what the South’s new Duck Dynastydeserves. In any case, the conventional wisdom goes, the struggle for the South is hopeless.

I beg to differ. As a preacher rooted in the Southern freedom movement, I find myself strangely hopeful at the beginning of 2016. Like Dr. King, I hold this hope as a moral conviction and a practical concern. But I, too, do not hold it without attention to the South as it is.

As in America’s First and Second Reconstructions, the South is crucial—and winnable—today. It matters not only because it is a region where American democracy has been envisioned, embattled, lost, and won for more than a century. It matters also because hard data, like those outlined in a 2014 Center for American Progress report, suggest that “registering just 30 percent of eligible unregistered black voters or other voters of color could shift the political calculus in a number of Black Belt states.” In North Carolina and elsewhere, black voters now turn out at percentages rivaling those of white voters, which is remarkable given the socioeconomic realities of the racial landscape. President Obama won North Carolina, Virginia, and Florida in 2008, and only narrowly lost North Carolina in 2012. Latino turnout rises every election cycle in North Carolina. And issues like healthcare, voting rights, and public education have sparked new “fusion” coalitions. If people of color in the South can learn to utter and understand new languages, a reshaped political landscape is possible through coalitions with Latinos, the LGBTQ community, labor, and religious progressives.

* * *

The question is not whether CNN will see this, but whether progressives themselves will see it. The patches of the fusion coalition in the South lie all around us: Black Lives Matter, Fight for $15, the Equality Federation, Southerners On New Ground, the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, the NAACP, and progressive churches. But progressives and liberals must learn not to throw away the moral high ground and walk away from religious discourse. At the heart of faith is love, justice, fairness, and a measure of mercy for all people. Many people get to a social ethos grounded in love by way of ethical reasoning or political tradition. But we must not write off the millions, from Baptists to Buddhists, who get there by way of a myriad of faith traditions.

Over the past decade here in North Carolina, we have witnessed the power of moral dissent to challenge the forces of injustice. Our adversaries have hijacked the concept of morality and shifted it to such personal matters as abortion and homosexuality. But by taking back the moral high ground on issues like Medicaid, voting rights, and poverty, our Moral Mondays movement won the support of a dozen major religious denominations and rallied tens of thousands in the streets of our cities and towns.

Though Democrats narrowly lost the 2014 US Senate race in North Carolina, our coalition mobilized voters of color at record levels. More than a thousand civil-disobedience arrests kept our issues in the news, which drove opinion polls sharply in our direction. The extremist legislature’s approval ratings fell to as low as 17 percent. The South as it is demands that we learn to hear and speak languages not our own in a fusion coalition that can usher in a Third Reconstruction.

This is why progressives must learn to “speak in tongues” toward a new political Pentecost, because the issues we face in 2016 are not matters of left and right; instead, they are matters of right and wrong. What religious tradition urges its devotees to fleece the poor and destroy public schools? What concept of God informs the believer that it is right to turn hungry children away from preschool programs where they can get a head start in life and a nutritious breakfast, or to deny poor children medical care and dentistry? What Scripture permits the beating of prisoners or refuses a person a fair trial? We have a genuine moral vision, and it is time that we embraced it.

* * *

Ten years ago, I became president of the North Carolina NAACP, promising to move us “from banquets to battle.” We soon learned something important about North Carolina: There wasn’t a huge crowd standing together in any one place, but if you added up all the different groups who were standing for their justice issues, the potential base for a coalition was large.

So we sketched a list of 14 justice “tribes” in North Carolina: folks committed to public schools, a living wage, access to healthcare, environmental justice, immigrant rights, redress for black and poor women forcibly sterilized in state institutions, the public financing of elections, affordable housing, and better funding for historically black colleges and universities. We had people battling discrimination in hiring, the death penalty, and the glaring injustice of our criminal-justice system. These tribes consisted of committed people who’d been working on their issues for years. Some had been able to mobilize thousands of people for a particular event, especially when their issue was a hot news item. What could happen, we asked, if we all came together for a People’s Assembly in the state capital?

Representatives of 160 organizations showed up and identified their issues. Then we asked them to list their enemies and obstacles. Though our issues varied, we all recognized the same forces opposing us. What’s more, we saw something we hadn’t had a space to talk about before: There were more of us than there were of them.

This was the beginning of North Carolina’s moral movement. We built power for seven years, winning several victories in coalition with other progressives. We passed same-day on-site voter registration and early voting before electing Barack Obama in 2008, thereby breaking the Republicans’ “Solid South,” which national strategists had relied on since Nixon’s 1968 Southern strategy.

This victory inspired the well-financed backlash that brought our movement national attention. When Republicans spent $30 million to take control of state legislatures in 2010, we saw their plan in action: Here in North Carolina, they defunded state government through a flat tax that increased the burden on poor people while giving the wealthiest a windfall; denied federally funded healthcare to half a million people; rejected federal unemployment benefits for 170,000 workers and their families; made dramatic cuts to public education; deregulated industries with a demonstrated record of environmental abuse; proposed a constitutional amendment to deny equal protection to gay and lesbian citizens; and passed the worst voter- suppression bill that America has seen in half a century.

In response, our Moral Mondays protests emerged as the largest state-focused civil-disobedience campaign in US history, because our coalition saw that this attack on North Carolina wasn’t just about us and our well-being. As the national electorate shifts to become majority nonwhite, reactionaries who would hold onto power have decided to remake government at the state level, especially in the South. On the ground in North Carolina, we’ve seen their agenda for the nation.

* * *

We stand together because we have learned in practice the importance of our shared history. Fusion politics emerged in the late 1860s, right after the Civil War, when blacks and whites together created a new electorate in the South. They rewrote state constitutions, guaranteed voting rights, and defended equal protection under the law. Fusion coalitions expanded labor rights and pushed progressive tax reforms to build the first public-school systems and address the economic injustices created by slavery. The same fusion spirit animated movements in several Southern states into the 1890s, when white conservatives, unable to beat them at the polls, crushed them with violence.

If these extremists are cagey enough to work together, we should be shrewd enough to unite against them.

Again in the 1950s and ’60s, fusion politics took on Jim Crow segregation. Blacks, whites, Jews, Catholics, Protestants, students, and labor unions united to create a new kind of politics: Rooted in opposition to racism and poverty, the new fusion movement displayed a deeply moral center along with a commitment to nonviolent direct action. The right to vote was essential, but the movement was far larger than that, standing against what Dr. King called the “thingification” of human beings and creating what he termed a new “sense of somebody-ness.” It won legal victories like Brown v. Board of Education and legislative milestones like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. None of this would have been possible, of course, without strategy in the streets.

Fusion history teaches us to see strength in coalition. Much like the First and Second Reconstructions, the forces fighting us on voting rights, educational equality, and racial disparities in the criminal-justice system are the same ones behind the attacks on LGBTQ rights. The advocates of huge tax cuts for the wealthy and greater burdens on everyone else are the same ones pursuing a new Jim Crow through voter-suppression bills and race-based redistricting. They are the forces refusing to expand Medicaid and driving the resegregation of our public schools. If these extremists are cagey enough to work together, we should be shrewd enough to unite against them. None of us can wait until our special issue is under fire and then try to rally the people.

We must commit to 21st-century fusion politics and build a multicolored movement. “I go back to the South,” Dr. King said, and we must see that our future is down in Dixie, in homegrown, state-based coalitions. If we win even a couple of states in the region, the presidency becomes a foregone conclusion and the movement will have blossomed.

* * *

Down here in North Carolina, we have been witnessing signs of a political Pentecost that offers a way forward together for the nation. A recent Southern voting-rights conference in Durham drew young organizers from across the South. Most were activists from the Moral Mondays movement, Black Lives Matter, the Dream Defenders, Southerners On New Ground, the NAACP, and other progressive groups. About a third of the attendees were venerable warriors from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, including Bob Moses, Dave Dennis, and other movement legends. Another third were solidly middle-aged voting-rights activists from Mississippi, Georgia, and North Carolina. And the final third were student activists, black and white.

Early on during our time together, a tension emerged when some participants dismissed Black Lives Matter in passing as “just a hashtag,” as if no “real” organizing had been going on. Certain elders also indulged the cliché that “We have the wisdom, but young people have the energy.” All of this infuriated the under-30 crowd of activists, who knew they had wisdom worthy of attention. The younger folks immediately stood up and called an early-evening caucus—young people only—and then a later session for everyone to hammer out our differences. Some thought the conference would soon break up (which wouldn’t be a first in movement meetings).

But the young people showed immense democratic poise. The spirit of Ella Baker seemed to guide their deliberations as they listened to one another closely and gave everyone a chance to speak. The conversation was as much poetry as prose, occasionally literally, as speakers cited spoken-word wisdoms and hip-hop visions. Fingers popped in acknowledgment of a point. A consensus began to form. At a later plenary, where their elders waited uneasily, the youth did some patient teaching. Dispelling any notion that energy was their lone asset, the young people turned to voting rights. Voting itself was important, they conceded, but only as part of a larger movement strategy. And the battle for voting rights had crucial consequences, they observed, but in large measure as a tool for recruitment. Only a movement could change things deeply enough.

The elders caught the spirit and recognized the power of this discernment. It was true, they said, and this was really the point. They had perhaps gotten lost in nostalgia for the voting-rights struggles of the past or distracted by the mere mechanics of the current ones. Building a movement was the point—and that could only happen by bringing together all of the pieces of our common struggle.

The spirit that emerged in that room is one we’ve seen stirring across the South. It was named well by the prophet Joel, whom St. Peter quoted at a Pentecost celebration some 2,000 years ago: “Your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions and your old men shall dream dreams.”

The signs we’ve witnessed in North Carolina point to a fresh political wind in 2016. A deep sense of unrest drives the success of both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. But the radically Pentecostal populism we’ve witnessed in the moral movement pushes us to consider the possibility of a higher ground for both parties. We’ve seen conservative preachers stand with LGBTQ activists to resist a constitutional amendment against marriage equality. Our rallies on the Statehouse lawn turned into old-style revival meetings where we came together in the most diverse gathering in North Carolina’s history, not only to celebrate our common future but also to put our bodies on the line in civil disobedience. Black, white, and brown; civil-rights and labor activists; gay and straight; rich and poor—nearly 100,000 of us marched on Raleigh together in the dead of winter. We went east and organized with a Republican mayor and the local NAACP to save a hospital in Belhaven. We went west and organized seven new chapters of the NAACP in counties that are majority Republican and nearly all white. And in the 2014 midterm elections, we defeated a number of Tea Party candidates in those western North Carolina counties where we planted young organizers.

* * *

We need this kind of moral fusion movement to build power for a Third Reconstruction. Even if morality is not your mother tongue, a Pentecostal moment means learning to speak new languages. But it also means learning to hear and understand them, seeing our common cause with sisters and brothers we didn’t know we had.

This much is certain: When the elders see visions and the young people dream dreams, something new is possible. My prayer for 2016 is that this new America might become the headline we can’t stop talking about.

The Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II is co-author of The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics and the Rise of a New Justice Movement, published in January 2016 by Beacon Press. In January 2016 he also began filing regular dispatches from the southern movement for racial justice for The Nation, resuming a role Martin Luther King Jr. once filled for the magazine. Rev. Barber II is the architect of the Forward Together Moral Monday Movement, president of the North Carolina NAACP and pastor of the Greenleaf Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in Goldsboro. He is also president of Repairers of the Breach. In 2015, he was the recipient of the Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative