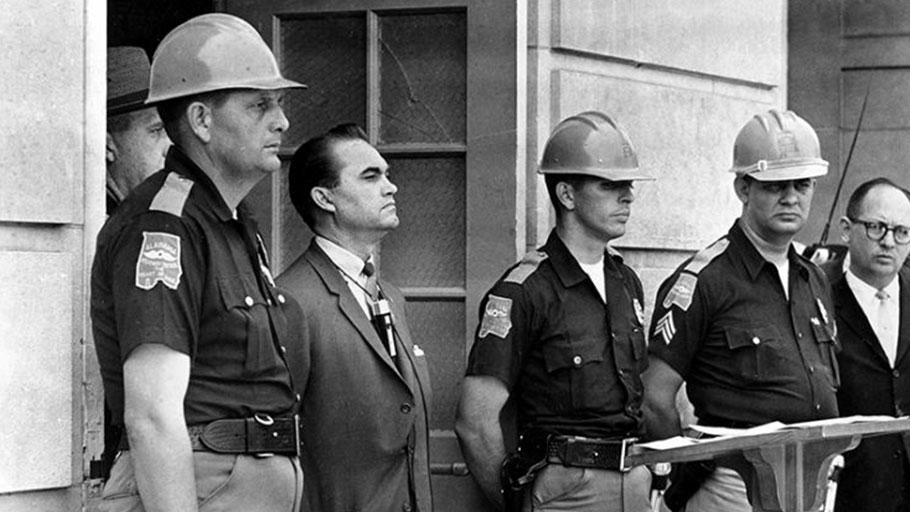

George Wallace blocking a federal agent from entering the University of Alabama to enroll Black students, 1963. Image: AP

In a political season of dog whistles, we must be attentive to how talk of American freedom has long been connected to the presumed right of whites to dominate everyone else.

By Jefferson Cowie, Boston Review —

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” Alabama governor George Wallace’s most famous sentence fired through the frigid air on the coldest day anyone in the state could remember. His 1963 inaugural address—written by a Klansman, no less—served as the war cry for the massive, violent response to the nonviolent civil rights movements of the 1960s. Wallace’s brand of right-wing populism would reconfigure U.S. party politics, making him, as his biographer put it, the “invisible founding father” of modern conservatism. As so many pundits have pointed out, when Donald Trump talks about “domination” today, he is talking the language and politics of Wallace.

Black Lives Matter protesters may have to go beyond tearing down Confederate monuments and ending police brutality to untangle one of the nation’s central ideological commitments: the freedom to dominate.

Yet Wallace’s famous speech was less about segregation than it was about freedom—white freedom. Other than its infamous applause line, the inaugural mentions “segregation” only one other time. In contrast, it invokes “freedom” twenty-four times—more times than Martin Luther King, Jr., used the word during his “I Have a Dream” address the following summer at the 1963 March on Washington. Freedom is this nation’s ill-defined but reflexive ideological commitment. Winding through the heart of that complex political idea, however, is a dark and visceral current of freedom as the unrestrained capacity to dominate. Today’s Black Lives Matter protesters may have to go beyond tearing down Confederate monuments and ending homicidal police brutality and stand before the challenge of untangling one of this nation’s central ideological commitments. Oppression and freedom are not opposites. They are mutually constructed, interdependent, and difficult to separate. As African American historian Nathan Irvin Huggins put it, “Slavery and freedom, white and black, are joined at the hip.” We remain burdened by the question posed by eighteenth-century English poet and essayist Samuel Johnson: “Why do we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of negroes?” In American mythology, there exists a gauzy past when white citizens were left alone to do as they pleased with their land and their labor (even if it was land stolen and labor enslaved). In the legend, those days of freedom and equality were, and still are, perpetually under assault. Most often the entity threatening to steal or undermine freedom in the American melodrama is the federal government. In the federal government’s checkered—perhaps “occasional” might be the better term—history of protecting minority populations from white people’s dominion, it presents a constant threat to the liberty of white people. That is why, as southern historian J. Mills Thornton put it, southern history—I would say U.S. history—displays an obsessive “fear of an imminent loss of freedom.” Understanding the anxious and fearful grind produced by threats to the domination-as-freedom complex helps us understand what Richard Hofstadter called the “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” of the “paranoid style” in U.S. politics. The government is not just coming for your guns, its coming for your freedom—the freedom to dominate others. The ancient republican societies to which the American revolutionaries looked for ideas and inspiration also had a problem with the fusion of freedom and slavery. As classicist Moses Finley explains about the ideological development of the old republics, “One element of freedom was the freedom to enslave others.” This had legal and political ramifications that rippled through Western history. The United States, from colonial times to the Civil War, inherited and reinvigorated the ancient republican values but did so in a setting of chattel slavery and settler colonialism, which caused white freedom to take its most virulent form. As Edmund S. Morgan explains in American Slavery, American Freedom (1975), white people could extol the entire republican package of equality, freedom, and democracy more effectively in a slave society than they could in a free one. As he puts it, what developed was “a rough congruity of Christianity, whiteness, and freedom and of heathenism, non-whiteness, and slavery.”

In American mythology, there exists a gauzy past when white citizens were left alone to do as they pleased with their land and their labor (even if it was land stolen and labor enslaved).

Fortunately, not all political dimensions of freedom rely on racial domination and slavery—and in that, there is hope. Historical sociologist Orlando Patterson sees the structure of Western freedom as having three notes that compose a single cultural chord. The first note is the most obvious: freedom as the absence of constraint on one’s latitude to act. This allows citizens to do as they please. We might consider this the high note of the Whitmanesque “open road”—the one most cherished by Americans and the most romantic version. The second note is “civic freedom”—the ability to participate in governance of one’s community, to create a space in which people have the means to pursue their “first-note” freedoms. We call this democracy. We are civically free to the degree we share in the decisions of governance. The problem, however, is Patterson’s third and most menacing note. Simultaneously the least understood and the most problematic is what Patterson calls “sovereign freedom.” This clunky term encompasses the freedom and capacity to wield power over others. With this dark note in the chord, freedom takes on something more menacing, more libidinal than we are accustomed to thinking about: freedom as the exercise of power, control, even violence. A free person, in this final sense, “has the power to restrict the freedom of others or to empower others with the capacity to do as they please with others beneath them.” Wallace’s racialized anti-statist brand of freedom reflects this final understanding. In his inaugural address, he summoned “the great Anglo-Saxon Southland” to “sound the drum for freedom” as waves of generations had done through history. “Let us rise to the call of freedom-loving blood that is in us,” he demanded, “and send our answer to the tyranny that clanks its chains upon the South.” Of course, he was not only rallying the South: he called upon all citizens across the nation to enroll in the fight against federal courts, federal troops, federal economic planning, and federal political control then threatening the white control over non-whites. His message caught fire across the north in his 1968 and 1972 campaigns for president. The defense of white freedom in U.S. history might more accurately be thought of as racialized anti-statism, in which the federal government is understood as a usurper of individual and states’ rights. As tortured as African Americans’ relationship to federal authority is, the federal government remains one of the most important civic tools for the protection of minorities from the unrestrained freedom of local, often racially motivated, majorities. Recall that managing to get some young African Americans into Little Rock Central High School alive took the civil rights movement, yes, but also the Supreme Court and the deployment of the 101st Airborne Division. Anti-statism runs deep. The fight against colonial authority (“tyranny”) and a belief in the supremacy of the people, narrowly defined, were central to both the mood of the American Revolution and the early republic. The Constitution, seen by many at the time as having gone too far in centralizing power, was created in the midst of widespread paranoia about conspiracy, corruption, and political “enslavement,” first by the colonial power of England and then later by the Federalists. By design, the Constitution limits federal authority to very specific levers of action. Segregationists thought of themselves as Jeffersonians—not because the great Virginian was a slaveowner but because he believed in limited government. As historian Jason Morgan Ward put it, the sense of dispossession of a birthright of white freedom continued through the twentieth century. “Whether comparing the New Deal to slavery, federal officials to carpetbaggers, or racial reformers to Nazis,” he argues, “postwar segregationists fused their fears into a racially charged anti-statism that echoed in future battles over the fate of the welfare state.”

The defense of white freedom in U.S. history might more accurately be thought of as racialized anti-statism, in which the federal government is understood as a usurper of individual and states’ rights.

The constitutional problem is key because what legal scholars call “police power”—the ability to regulate and enforce behavior in the name of the welfare of the people—rests officially with the states. The federal government is therefore specifically designed to be a thing of political restraint, while state governments are given broad latitude of action. Most political questions are left to the states, as per the Tenth Amendment, in what James Madison dubbed the “compound republic.” Some of the most dramatic episodes in political history have occurred when the federal government threatened the freedom of local authority. Confederate elites mobilized to defend the institution of slavery on which their belief in freedom rested, but many rank-and-file soldiers fought to preserve from state tyranny the individual liberty that they believed had been won in the American Revolution. When Reconstruction threatened local white freedom with federal authority over race relations, the South—with many northern allies—defended its sovereignty. For southern revanchists, even lynching was construed as a form of freedom: in Ashraf H. A. Rushdy’s intellectual archaeology American Lynching (2012), he points out how the power of racial terror “arose precisely out of an ideology of the sense of what rights accrued to someone possessing democratic freedom.” For white people, the capacity for violence and murder was their “birthright, their heritage, the final statement of their freedom.” This is the same ground on which people fought the federal intrusions of the New Deal, and, on which Wallace stood when he blocked federal marshals at the “schoolhouse door” to oppose the integration of the University of Alabama. A year and a half after Wallace’s inaugural, the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed. As a result, his accusations about federal incursions into Alabama’s freedom became all the more histrionic. Calling federal legislation to treat African Americans equally an “act of tyranny,” Wallace described it as “the assassin’s knife stuck in the back of liberty.” The “federal force-cult”’ was trying to push the white South “back into bondage.” The liberal state, he argued, asserted “more power than claimed by King George III, more power than Hitler, Mussolini, or Khrushchev ever had.” In his runs for the presidency in 1964, 1968, and 1972, Wallace put the lie to the notion that his politics were provincial. He effectively captured a rightward-shifting electorate in his demand for freedom from federal “oppression,” winning a number of states in the 1964 and 1972 primaries and the 1968 general election. Libertarian values never had much truck on their own, as Barry Goldwater found out in his landslide loss in 1964 in which his anti-statist message only won the Deep South and his home state of Arizona. But when libertarian values are stitched together with Wallace’s version of racialized freedom, the nation embraced the double helix of American conservatism: racism plus freedom. Together they proved a powerful tandem of resistance to federal authority that has redefined U.S. politics. If the protests taking place under the broad umbrella of Black Lives Matter ultimately achieve lasting change, it is realistic to believe they will do so by furthering the creation of constitutional powers to curtail white freedom—akin to those of Reconstruction in the 1860s and 1870s, Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, and the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 respectively. Further incursions of federal authority will generate further cries for freedom as they have since the dawn of the republic. The backlash dialectic is predictable but imperative.

If Black Lives Matter protests ultimately achieve lasting change, it is realistic to believe they will do so by furthering the creation of constitutional powers to curtail white freedom.

By recognizing power, race, and the capacity for violence as core dimensions in what freedom means and how it moves, we gain a fresh perspective on central problems in American ideology. Such a framework begins to explain why cries for freedom so often exist in an uncomfortable romance with racial bigotry, religious intolerance, misogyny, land hunger, violence, and a belligerent form of gun rights. Freedom was used to steal land from Native Americans, defend slavery, defeat Reconstruction, justify lynching, fight the New Deal, oppose civil rights, elect Trump, and label Black Lives Matter as seditious. The federal government has a shaky record of opposing state-level visions of liberty and autonomy, but when it does manage to do the right thing, the blowback against federal “tyranny” is often wildly out of proportion to the real scale of federal action. In the eyes of many, the federal government is an enemy—even the enemy—of white American freedom. Abraham Lincoln, who himself had to play aggressively with the wartime Constitution to achieve his goals, certainly understood this. In 1864 he spoke to the people of Baltimore about a future without slavery. “The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty,” he explained. The nation in the midst of the Civil War was in need of one. “We all declare for liberty, but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing,” he puzzled. “With some the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself, and the product of his labor; while with others the same word may mean for some men to do as they please with other men, and the product of other men’s labor.” The fate of the country hung in the balance between competing ideas: two different parties could see the same thing and call it “by two different and incompatible names—liberty and tyranny.” Lincoln developed his thinking, as he often did, by way of parable. “The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as a liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty, especially as the sheep was a black one,” he explained. “Plainly the sheep and the wolf are not agreed upon a definition of the word liberty; and precisely the same difference prevails to-day among us human creatures, even in the North, and all professing to love liberty.” Lincoln continued to argue that as slavery came to end, it would be “hailed by some as the advance of liberty, and bewailed by others as the destruction of all liberty.” Perhaps the Railsplitter omitted the end of the story: the shepherd is going to protect the sheep just long enough to slaughter it in his own way. When officer Derek Chauvin forced his knee into George Floyd’s neck until he could breathe no more, he acted from the darkest reservoirs of the nation’s fundamental creed. We must consider whether Floyd died so Chauvin could feel free. We can scoff at the rise of today’s neo-Confederate ideas of freedom, but it’s worth noting that they are, in fact, actual freedom fighters within a deeply flawed American idiom. Wallace’s vision of freedom still competes aggressively with the hopeful and expansive vision of freedom that animates Black Lives Matter. So, is freedom white? Partially, yes. When the Second Amendment is used to trump the First; when the Tenth Amendment is used to fight African American voting and citizenship; when the government buckles in the face of armed white resistance; when a slaveholders’ Constitution defeats the spirit of the Declaration of Independence; when neo-Confederates call themselves freedom fighters; when the most oppressive institution in the House of Representatives is called the Freedom Caucus; when William Barr can even loosely compare COVID-19 stay-at-home orders with slavery; when a wannabe dictator such as Trump claims, as he did in his most recent State of the Union, that “freedom unifies the soul,” then the answer is: yes, core dimensions of freedom are still white. In those cases, the dark note of freedom dominates the other notes in Patterson’s cultural chord to the profound detriment of our democracy. Ta-Nehisi Coates denounces the contemporary power of what he calls “white freedom” in a 2018 essay on Kanye West. It is, he argues:

freedom without consequence, freedom without criticism, freedom to be proud and ignorant; freedom to profit off a people in one moment and abandon them in the next; a Stand Your Ground freedom, freedom without responsibility, without hard memory; a Monticello without slavery, a Confederate freedom, the freedom of John C. Calhoun, not the freedom of Harriet Tubman, which calls you to risk your own; not the freedom of Nat Turner, which calls you to give even more, but a conqueror’s freedom, freedom of the strong built on antipathy or indifference to the weak, the freedom of rape buttons, pussy grabbers, and fuck you anyway, bitch; freedom of oil and invisible wars, the freedom of suburbs drawn with red lines, the white freedom of Calabasas.

But there is promise in this moment: the hope of a third Reconstruction in this era of Black Lives maybe actually Mattering. Impatience serves us poorly when working to dismantle a core element of a nation’s belief system. Few tasks could be more important, urgent, or have higher stakes than the ongoing struggle to purge the United States of the burdens of white freedom

Source: Boston Review