“I’ll be very, very honest with you. The South has not always been the friendliest place for African-Americans,” she told NBC News in an interview. “It’s been a difficult time for the president to present himself in a very positive light as a leader.”

This is hardly earth-shattering news from the state that brought us Plessy v. Ferguson in the 1890s, and the deeply racialized devastation of Katrina less a decade ago, after which even President Bush admitted that “deep, persistent poverty” in the area “has roots in a history of racial discrimination, which cut off generations from the opportunity of America.” Speaking of Katrina, according to a PPP poll last year, the good people of Louisiana “were evenly split on who was most responsible for the poor Hurricane Katrina response: George W. Bush or Obama, 28/29.” Given that Obama was a first-year senator at the time of Katrina, it’s not hard to see what Landrieu was driving at.

What’s more, the role of race was only a tertiary matter in Landrieu’s account. When asked why the president had such a hard time in the state, Landrieu first said it was “because his energy policies are really different than ours,” then when pushed further, she added, “because he put the moratorium on offshore drilling,” after the disastrous BP oil spill.

It was only after laying out those policy complaints that Landrieu got around to discussing race. Yet, predictably, fourth-tier 2016 GOP presidential wannabe Bobby Jindal, Louisiana’s governor, instantly made an ass of himself, calling her comments “remarkably divisive,” which takes a lot of chutzpah, coming from a racial panderer who just three years ago pledged he would sign a “birther” bill if it reached his desk.

Jindal also claimed that “the people of Louisiana are willing to give everyone a fair hearing,” a claim belied by that PPP poll, and that certainly didn’t apply to Jindal’s own exclusive focusing on Landrieu’s tertiary reference to race. Nor does it comport with the tenacity of birtherism, which has only grown more intense, the more thoroughly it’s been discredited.

Birtherism, you see, has become the GOP’s more widespread manifestation of racial codespeak in the Obama era. Although Obama deftly quieted the elite media trolls with the release of his long-form birth certificate just after Donald Trump had ridden birther hysteria to the top of the GOP primary field in April 2011, the GOP base was never really dissuaded. In fact, nine months later, in January 2012, a YouGov poll found that more Republicans than ever questioned Obama’s citizenship. Those denying his American birth outright were up 50 percent, from 25 percent of all Republicans to 37 percent, while those accepting his American birth were down 10 percent, from 30 percent to 27 percent of all Republicans. Indisputable hard evidence did nothing at all to dissipate the birther delusion, it only made it stronger. That’s not something Mary Landrieu made up. The GOP’s own partisan media did that.

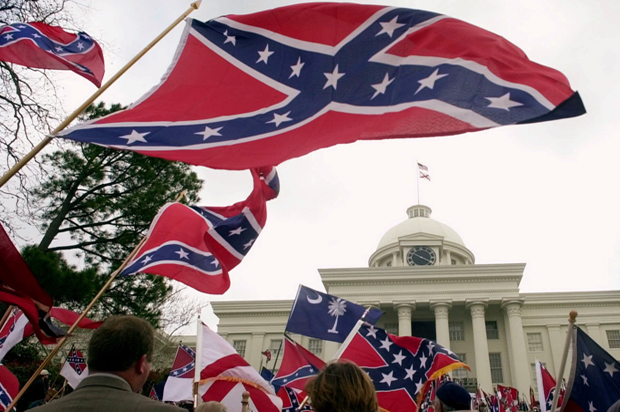

Although birtherism is a complex phenomenon in its own right, Landrieu — like Bush before her — was referencing a much broader problem facing Obama, as well as herself, and the Democratic Party as a whole. You’re not supposed to call it “racism,” because racism means KKK mobs in hoods, and police siccing snarling dogs on young children, and we’re not like that anymore — see, we’ve got armored vehicles and sound cannons now!

But 40 years of data from the General Social Survey — the gold standard of American public opinion research — say otherwise. They tell us that Southern whites overwhelmingly blame blacks for their lower economic status, ignoring or denying the role played by discrimination, past and present, in all its various forms, and that the balance of Southern white attitudes has barely changed at all in 40 years. At the same time, attitudes outside the white South have shifted somewhat — but still tend to blame blacks more than white society, steadfastly ignoring mountains of evidence to the contrary — such as 60 years of unemployment data, over which time “the unemployment rate for blacks has averaged about 2.2 times that for whites,” as noted by Pew Research. It is only Democrats outside the white South who have dramatically shifted away from blaming blacks over this period of time, and the tension this has created within the Democratic Party goes to the very heart of the political challenge both Obama and Landrieu face — a challenge that is not going to simply go away any time soon.

Before turning to the GSS data, it’s worth noting that it’s hardly an anomalous finding. A 2011 study from Tufts (press release/full study) found that whites as a whole see racism as a zero-sum game, such that decreases in discrimination against blacks over the decades are reflected in increases in discrimination against whites, so that now whites are more discriminated against than blacks. This perception is not simply mistaken, it’s downright delusional, flying in the face of mountains of objective data. For example, a June 2014 study by Young Invincibles, “Closing the Race Gap,” found that blacks need to complete two more levels of education to have the same probability of employment as their white counterparts. Nonetheless, as explained in the Tufts press release:

On average, whites rated anti-white bias as more prevalent in the 2000s than anti-black bias by more than a full point on the 10-point scale. Moreover, some 11 percent of whites gave anti-white bias the maximum rating of 10 compared to only 2 percent of whites who rated anti-black bias a 10. Blacks, however, reported only a modest increase in their perceptions of “reverse racism.”

It’s a striking finding, but it only represents a snapshot in time. The GSS, in contrast, has 40 years of data, and allows us to analyze geographical and political subgroups as well. Since the 1970s, the GSS has included four questions about the causes of blacks’ lower socioeconomic status. Specifically, it asks, “On the average (negroes/blacks/African-Americans) have worse jobs, income, and housing than white people. Do you think these differences are

a. Mainly due to discrimination?

b. Because most (negroes/blacks/African-Americans) have less in-born ability to learn?

c. Because most (negroes/blacks/African-Americans) don’t have the chance for education that it takes to rise out of poverty?

d. Because most (negroes/blacks/African-Americans) just don’t have the motivation or willpower to pull themselves up out of poverty?

Of these four alternatives, (b) is a blatant example of classical racism, endorsed by the white conservative establishment, as in Charles Murray’s “The Bell Curve,” but widely seen as beyond the pale in America today. In fact, it’s precisely the fact that most people don’t think this way anymore that convinces so many whites that racism is a thing of the past.

While just over one-quarter of all respondents agreed with (b) in the 1970s, just a hair more than 1 in 10 agreed by the 2000s. More important, fewer than 2 percent cite it alone as the reason for blacks’ lower status, as opposed to more than 12 percent who cite it along with lack of effort. Hence we are well advised to set it aside as a relatively peripheral attitude. We are also well advised to set aside the question of education, which can either be interpreted as something blacks are responsible for — parents failing their children, for example, or something that is being done to them through lack of adequate resources.

In contrast, (a) and (d) provide clear alternative explanations, either blaming blacks themselves (lack of motivation or willpower) or white society (in the form of discrimination), and they are relatively widely held. Although there were some shifts over the decades, no position on either of them was ever an extreme outlier position. Indeed, the lowest levels of support for any alternative, pro or con, were just over one-third for each alternative: In the 1970s, 35.3 percent said differences were not due to lack of will — which increased each decade, culminating at 50.3 percent in the 2000s — while 35.7 said differences were due to discrimination in the 2000s, down from a high of 44.6 percent in the 1980s. Thus, throughout the entire 40-year period covered by the GSS, these two alternative explanations have remained relatively prominent throughout. A scale combining them captures whether an individual subscribes to the most common explanations that either blame blacks (saying “no” to [a] and “yes” to [b]), blame white society (the reverse), or blame a combination of the two (“yes” to both or “no” to both).

Using that scale, we find that there has been only a modest overall change in attitudes since the 1970s, but that this change is significantly concentrated in the Democratic Party, with relatively minor changes in the Republican Party, and somewhat larger changes among independents — though in a surprising way. Most important, the change within the Democratic Party has left Democrats in the white South blaming blacks exclusively more than they blame discrimination alone, whereas the rest of the Democratic Party takes the opposite view. This divergence in attitudes goes to the very heart of the political problems that Landrieu was wrestling with, even in trying to describe what they were.

Overall responsibility for external forces — discrimination against blacks, and no lack of effort or will — has increased 7 percent (from 21.0 percent in the 1970s to 22.6 percent in the 2000s), while responsibility for internal forces —black lack of effort and will, with no discrimination — has decreased 18 percent (from 45.1 percent to 37.1 percent). The ratio of the two — internal causes to external ones — has declined 77 percent, from 2.1 in the 1970s to 1.6 in the 2000s. But if we break down the population by party, we see strikingly different trajectories. Democrats have changed a lot. Republicans and independents, not so much.

Among Democrats, responsibility for external forces has increased 51 percent (from 20.8 percent to 31.4 percent), while responsibility for internal forces has decreased 33 percent (from 45.7 percent to 30.5 percent). Combining these two shifts, the ratio of the two has declined 56 percent (from 2.1 to 1.0).

Among Republicans, the shifts have been fairly insignificant: responsibility for external forces has not changed at all, it was 13.2 percent in the 1970s as well as the 2000s — though it did rise to a high of 19.0 percent in the 1980s, before declining back to its previous level. Responsibility for internal forces has decreased 7 percent (from 49.7 percent to 46.5 percent). The ratio of the two has declined 7 percent (from 3.8 to 3.5), a far cry from the dramatic shifts seen among Democrats.

The shifts among independents actually make the Republicans look good — although the absolute levels do not. Responsibility for external forces has dropped significantly, 21 percent (from 26.9 percent to 21.4 percent), while responsibility for internal forces has decreased just 8 percent (from 40.5 percent to 37.1 percent). Combined, the ratio of the two has increased 15 percent (from 1.5 to 1.7). Although independents have tended to shift blame more toward blacks themselves, compared to Republicans, over the past 40 years, in absolute terms Republicans are still twice as likely to place the blame on blacks compared to independents.

This is nationwide, and it paints a very stark picture. While Republicans still overwhelmingly tend to blame blacks for their lower socioeconomic status, Democrats are evenly split — a situation that makes it politically challenging for them to craft a coherent political strategy and message on issues of racial justice. This would be sobering enough in itself, but the picture is dramatically complicated when we look at the cultural divide between the white South and the rest of the country.

While the shift in Democratic attitudes was relatively uniform and dramatic, the underlying levels were not, and this has produced a sharp intra-party difference in attitudes. Democrats outside the white South are the only group that blames external factors in white society more than internal factors in blacks themselves. Although Southern Democrats are far less inclined to blame blacks than their GOP counterparts, they still blame blacks more by a ratio of 2.3-to-1, which is significantly less friendly to blacks than folks outside the white South are. In fact, Republicans outside the white South are almost as sympathetic to blacks as white Southern Democrats are: they blame blacks more by a ratio of 2.7-to-1.

Not only is the Democratic Party split between two dominant views — one in the white South blaming blacks more, the other outside it blaming discriminatory practices in white society more — the minority group within the party, white Southerners, is far more unified in its views.

In the white South, 42.4 percent blame blacks exclusively, compared to just 18.8 percent who blame discrimination, and 38.8 who blame both. That’s a lopsided 69/31 split between the two exclusive positions. Outside the white South, 27.7 percent blame blacks exclusively, 34.4 percent blame discrimination, and 37.9 percent blame both, a much narrower 45/55 split between the exclusive positions.

What all the above boils down to is that blaming blacks for being poor remains broadly popular in America today, and that taking note of continued discrimination is not. A modest majority of Democrats outside the white South disagree, and this creates a political fault line that Republicans have repeatedly exploited across the decades, with no end in sight. When conservatives get too crude — as was the case with Cliven Bundy, for example — this threatens to upset the apple cart, and appearances must quickly get restored. But it’s the crudity, not the underlying attitude of blaming blacks, that has fallen out of favor. This would hardly surprise a Southern gentleman of this or any other century. It’s just the way things are supposed to be. Always have been. Why ever change?

Paul Rosenberg is a California-based writer/activist, senior editor for Random Lengths News, and a columnist for Al Jazeera English. Follow him on Twitter at @PaulHRosenberg.