Jerome Taylor, PhD1

BY JUSTICE I MEAN THE ACHIEVEMENT OF RACIAL EQUITY estimated here as the ratio of black over white achievement proficiencies in reading and math. Where this ratio is 1.0 which would correspond to an equity estimate or 100%, educational justice is achieved. Metrics and arguments introduced in this commentary may in part be extended to any culturally or socially marginalized group in America or beyond.

According to the 2013-2015 report of NAEP scores released by the National Center on Educa- tional Statistics on 12th graders (2016), the 2015 black over white equity ratio in reading is 37% (17/46) in math and 22% (7/32) in reading, each falling dramatically short of our equity standard by 63 and 78 percentage points, respectively. Are we now heading in the right direction? The answer is ‘no’ since identified gaps in math and reading have not narrowed statistically for the most recent period 2013-2015.

The march toward freedom, defined here as fair and unfettered access to our nation’s educa- tional, economic, and occupational opportunity structures, is deterred, redirected, derailed, or reversed by failures in justice. Given the startling magnitude of these documented failures, is it altogether surprising that blacks obtain master’s degrees at a rate that is 38% of whites (educa- tional indicator)? Report net worth that is 8% of whites (economic indicator)? Enter computer and technology professions at a rate that is 11% of whites (occupational indicator)? This denial of freedom, black access to America’s still colorized fountains of educational, economic, and oc- cupational opportunity, is exacerbated by failures in justice. Under an agenda of full emancipa- tion, which our nation has yet to enable, justice potentiates freedom and freedom potentiates justice. Failure in either constrains or undermines attainment of the other.

In my view, here’s the major impediment to enabling a full agenda of emancipation where justice reigns and freedom rings: Nearly 50 to more than 90 percent of our ‘best and brightest’ of all races, ethnicities, and genders within and outside activist or religious communities in America and beyond still unselfconsciously and sometimes consciously embrace attitudes that demean the humanity of blacks (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013). Even in 21st Century America, blacks are still perceived as ape-like (Goff, Eberhardt, Williams, & Jackson, 2008) which ‘explains’ why they are mentally defective intellectually and morally and physically gifted athletically and sexually (Taylor & Kouyaté, 2003). Indeed there is evidence from neuroimaging studies that members of highly stigmatized groups are not even encoded in the brain as human beings (Harris & Fiske, 2006)— an implication not far removed from the leitmotif of Ralph Ellison’s (1952) classic The Invisible

1 Chair, Department of Africana Studies, University of Pittsburgh, Oakland Campus; President and Founder, Center for Family Excellence, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA. He is recipient of the Distinguished Psychologist Award of the Associa- tion of Black Psychologists; the Alan Lesgold Award for Excellence in Urban Education; the University of Pittsburgh Chancellor’s award for Public Service; and the Civil Rights Award from Black Alumni of the University of Pittsburgh.

1

Man. It seems reasonable to assume that these implicit and explicit biases sway information pro- cessing at every level: decoding, what we ‘see’ or notice about black students; encoding, what gets triggered in pre-existing memories by what we’ve ‘seen’; judging, how pre-existing memo- ries intersect with current perceptions to inform assignment of meanings to what we’ve ‘seen’; and behaving, what we do consciously or unselfconsciously because of meanings assigned to what we’ve ‘seen’. Although this is an oversimplified view of how implicit and explicit attitudes inform behavioral intentions and actions, a quite voluminous and persuasive literature does link implicit attitudes in general to a wide range of discriminatory policies and practices linked to outcome disparities or inequities in educational as well as employment, welfare, banking, hous- ing, and health systems.

Deeply troubling is the niggling realization that our nation has neither discovered nor imple- mented ways and means of resolving conjoined challenges of justice and freedom over the nearly 400 years blacks have been in America. Although four centuries of unrequited stereotyping is a very long time, I draw hope from the ancient wisdom of a Malawian proverb: No matter how long a log stays in the water it doesn’t become a crocodile, meaning exposure to adversity for however long does not change one’s essential nature. But how do we go about reclaiming the humanity of blacks—muting, challenging, unraveling, and displacing unselfconscious and conscious stere- otypes shared and embraced for so long by the nation’s majority and minority of all social ranks?

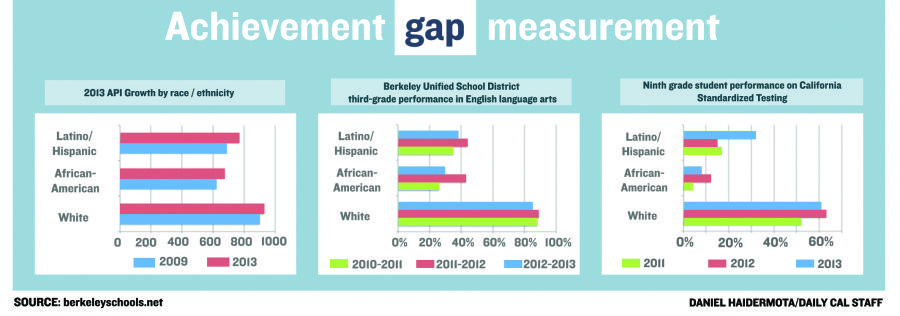

First, failures in justice and freedom have to be ‘sculpted’ in bas-relief by our measurement and evaluation communities. Although most polls indicate that Americans still possess an appetite for justice (equity) and fairness (freedom), we routinely fail to communicate persuasively our desperate need for both in the field of education. For example, reporting that we have a 25 point racial achievement gap in reading may carry less urgency than saying we have 78 percentage points to go before achieving equity—there’s more road ahead of us than behind us. For identical reasons, I recommend reporting efficiencies: Given the rate of gap closure from time X to Y, how many extrapolated years would it take to close the gap altogether? Finally, I support reporting of sufficiencies: Given the current level of black proficiency on NAEP (or whatever standard is used), to what extent are black students positioned to compete globally (using internationally adminis- tered tests like the TIMMS or PIRLS as reference points)? The basic expectation here is that broad and strategic distribution of equity, efficiency and sufficiency data is likely to quicken and sustain public interest in addressing failures in justice and freedom. These three dimensionizable and visualizable standards, then, we expect will (a) provide just the bas-relief required to capture and accentuate already existing public interest in matters of justice and fairness and (b) offer stand- ards for evaluating the justice and freedom potential of all existing and proposed reforms.

Second, we must highlight more consistently local and national costs of failures in justice and freedom. At the local level, failures in educational justice are strongly linked to incarceration rates, underdevelopment of entrepreneurial initiatives, diminished levels of home ownership, higher risks of residential dislocation, diminished political participation, lower rates of traditional family formation, larger mental and physical health disparities, and truncated life expectancies. At the national level, studies have shown that yearly achievement gaps shrink our national GDP to the equivalent of an annual recession. The first recommendation which establishes that there

2

is a problem in the delivery of justice and freedom operates in tandem with this recommendation which examines why a remedy must be sought in resolving it. Together, these recommendations are intended to pique high levels of public discourse and dissonance that I believe may be needed to drive and sustain discovery of solutions that have alluded us for nearly four centuries—this including the NCLB 2005-2014 years when nearly $113,000,000,000 in Title I funds were spent to bring justice to America’s children by 2014.

Third, we must discover through sponsored research and demonstration projects new ways of healing and preventing cultural wounding—unselfconscious or conscious construal of blacks as more ape-like than human. This denial of black humanity is consequential. Blacks in Africa, the Caribbean, and America who have internalized racist concepts tend to have higher rates of high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, and type 2 diabetes (Butler, Tull, Chambers, et al., 2002); report higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and hostility (Taylor, 1998); commit more hei- nous black-on-black crimes (Terrell & Taylor, 1980); report less satisfaction in intimate relations (Taylor, 1990); consume more beer, wine, and hard liquor (Taylor & Jackson, 1990a, 1990b); and attain poorer educational, occupational, and income outcomes (Murrell, 1989). Within educa- tional settings we must discover through dedicated research and demonstration how to heal the wounded and prevent the wounding of principals, teachers, students, and local neighborhoods. Here, I consider our Values for Life initiative which among several objectives strives to promote self-persistence in grades pre-K through 12 (Taylor, Turner, & Lewis, 1999). Our promotion of self-persistence is conceptually close to the mindset ‘grit’ but in our appropriation, self-persis- tence is intentionally culturalized to counter unselfconsciously held stereotypes about blacks. In one HS 9-12 application we introduce the picture and biography of Wilma Rudolph (1940-1994), the first American woman runner to win three gold medals in the Olympic Games. Her perfor- mance was all the more remarkable in light of the fact that she was 1 of 22 children, had double pneumonia, scarlet fever, and polio from birth. She had a crooked leg which required metal braces and four massages each day from age 5 until she was 11. Some said she would never walk. But one Sunday morning at age 11 she walked down the aisle of her church. Her black life epito- mized our concept of self-persistence which students are invited to claim through a series of three prompts: Social—Do you know people who show high self-persistence? What are they like? Educational—If students in your school showed high self-persistence, what would your school be like? Normative—Is there a friend or someone in your family you’d you like to introduce Wilma Rudolph to? Will you promise to do so this week? During class time, the behavior of students exemplifying self-persistence is culturally reinforced: Wilma Rudolph would be proud of you! Stu- dents exemplifying self-persistence consistently are awarded a personally inscribed African sym- bol of self-persistence which they take home with parental request to post it on the refrigerator door. Neighborhood stores also collaborate by hanging posters of students exemplifying self- persistence which customers including family, friends, and strangers are invited to autograph. Our intervention, intended to unsettle, weaken, and displace racist stereotypes, is associated also with accelerated math and reading performance. We found for third graders attending a high poverty almost all black public elementary school that teachers fall ratings of the behavioral expression of self-persistence were associated with students spring performance on standard- ized measures of reading and math achievement. Students rated by teachers as above the me- dian on self-persistence were eight times more likely six months later to score at or above the

3

national average on ITBS Math than students rated below the median on self-persistence. Stu- dents rated above the median on self-persistence were six months later 2.5 times more likely to score above the national average on SAT9 Reading than students who were rated below the me- dian. On this third grade sample, we found as well a 14 point gain in math and 29 point gain in reading proficiencies at the end of the first year of implementation (Taylor & Kouyaté, 2003). Unfortunately we are unable to determine the unique role of our culturalized ‘grit’ application because other values were also implemented throughout the year in this elementary school ap- plication. Similarly, we are unable to parse unique effects of our model implemented also in a predominately black high poverty secondary charter school where we found 13.6 and 30.6 point gains in state reading and math proficiencies following two years of implementation (Taylor, 2014). In general, we are clear that Values for Life interventions seek dedicatedly to heal and prevent cultural wounding in students who receive it, teachers who deliver it, principals who support it, and neighborhoods that celebrate it. We invite and encourage comparisons of our model with mindset and other socio-cognitive interventions, particularly in terms of the capacity of each to unsettle and displace unselfconsciously and consciously held racial stereotypes. In such comparisons, we expect our three evaluation strategies—equity, efficiency, sufficiency—will re- veal which of these intervention types is most likely to deliver justice and freedom.

Fourth and finally, we begin by noting that current reforms feature a wide range of outside-the box interventions: cognitive, affective, social, cultural, economic, pedagogical, and curriculum enhancements along with pre-professional training, professional development workshops, and high-stakes entrepreneurial models. Although most of these reforms have documented positive incremental change, none has consistently closed or reversed racial, socioeconomic, or black male gender gaps in public school settings. From the perspective of black families and communi- ties, all these models have failed to deliver educational justice to their children. Instead of looking outside these communities for justice, why not look inside these communities for solutions? For example, several years ago we identified 107 K-12 predominately black low-income public schools located in 16 metropolitan areas which had nearly closed or actually reversed racial, so- cioeconomic, and black male gender gaps. Although fewer than 5% of these inside-the-box schools had received our nation’s highest Blue Ribbon Award for exemplary achievement, we have initiated small-scale studies on policies and practices shared by these gap closing and re- versing schools. Like lilies of the field strutting their glorious bloom in compromised environ- ments, these inside-the-box schools produce spectacular results under adverse circumstances— in high poverty household and neighborhood environments with elevated levels of teenage preg- nancy, gang formation, juvenile delinquency, drugs and alcohol, and black-on-black crime. Here student destiny is not shaped by student zip code. Dedicated funding must be made available to support and expand our understanding of how these inside-the-box schools absolutely and res- olutely defy racist claims and affirm black humanity. We include here as well those Afrocentric choice and charter schools identified by Teasley, Crutchfield, Williams-Jennings, et al., 2016) that have closed racial achievement gaps. This may be the chance of a cultural lifetime now spanning nearly 400 years to honor and actionalize the wisdom of our ancestors: No matter how long a log stays in the water it doesn’t become a crocodile.

4

References

Banaji, M. R. & Greenwald, A. G. (2013). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. NY, NY: Delacorte Press.

Butler C., Tull, E.S., Chambers, E. C., & Taylor, J. (2002). Internalized racism, body fat distribution, and abnormal fasting glucose among African Caribbean women in Dominica, West Indies. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(3), 143 148.

Ellison, R. W. (1952). Invisible Man. NY, NY: Random House.

Harris, L. T., & Fiske, S. T. (2006). Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuroimaging responses to ex-

treme out-groups. Psychological Science, 17, 847–853.

Murrell, A. (1989). Social support and ethnic identification as predictors of career and family roles of Black women. Paper presented at the 21st Annual Convention of the Association of Black Psycholo- gists, Fort Worth, Texas.

National Center for Educational Statistics (2016). http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/

Taylor, J. (1990). Relationship between internalized racism and marital satisfaction. Journal of Black Psy-

chology, 16, 45-53.

Taylor, J. (1998). Cultural conversion experiences: Implications for mental health research and treatment

In R.L. Jones (Ed.), African American Identity ‘ Development, 2, 85-95, Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry.

Taylor, J. (2014). III. Toward a general theory of just outcomes: Pilot applications to just academic, voca- tional, and health outcomes. Invited submission to President Obama’s White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans. Department of Africana Studies, University of Pitts- burgh.

Taylor J., & Jackson B. B. (1990a) Factors affecting alcohol consumption in Black women: Part I. Interna- tional Journal of the Addictions, 25, 1287-1300.

Taylor J., & Jackson B. B. (1990b). Factors affecting alcohol consumption in Black women: Part II. Interna- tional Journal of the Addictions, 25, 1415-1427.

Taylor, J., & Kouyaté, M. (2003). Achievement gap between Black and White students: Theoretical analy- sis with recommendations for remedy. In A. Burlew, B. Guillermo, J. Trimble, & F. Leung, (Eds.), Handbook of racial ethnic minority psychology (pp. 327-356). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Taylor, J., Turner, S., & Lewis, M. (1999). Valucation: Definition, theory, and methods. In R.L. Jones (Ed.), Advances in African American Psychology, Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry.

Teasley, M., Crutchfield, J., Williams-Jennings, S.A., Clayton, M.A., & Okilwa, N.S.A. (2016). School choice and Afrocentric charter schools: a review and critique of evaluation outcomes. Journal of African American Studies, 20(1), 99-119.

Terrell, F. & Taylor, J. (1980). Self-concept of juveniles who commit Black on Black crimes. Corrective & Social Psychiatry & Journal of Behavior Technology, Methods & Therapy, 26(3), 107-109.