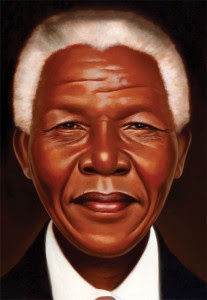

Nelson Mandela is portrayed as a solitary leader who rose above his people, instead of being part of a liberation movement. Images: (l) Nelson Mandela and friends sing ‘Nikosi Sikelel I Afrika’ at the end of their trial for treason in South Africa, 3/29/61. (r) Image from the picture book Mandela.

Mandela, the beautifully illustrated children’s book by Kadir Nelson, has been selected as one of the top books on Nelson Mandela by many groups including Colorlines and Kirkus Reviews. Given Kadir Nelson’s talents and strong reputation as a children’s book author and illustrator, Mandela is likely to become a staple in libraries and classrooms.

One look at the cover and it is easy to see why the book is so popular. Kadir Nelson’s illustrations are stunning and the world is tuned into Mandela with his recent passing and the release of the film, Mandela: The Long Walk to Freedom.

One look at the cover and it is easy to see why the book is so popular. Kadir Nelson’s illustrations are stunning and the world is tuned into Mandela with his recent passing and the release of the film, Mandela: The Long Walk to Freedom.

Unfortunately, Kadir Nelson’s picture book presents the same mythological image of Mandela that has been the norm on the mainstream news. As journalist Bob Herbert lamented, the news media have reduced Mandela to a “to a lovable, platitudinous cardboard character” and the vital role of the anti-apartheid struggle is effectively obscured in the process.

The mythmaking in Mandela begins with the book jacket: “Mandela saw fellow Africans who were poor and powerless. He decided he would work to protect them.” The picture book text repeats this image of Mandela-the-savior: “…Africans were poor and powerless. Nelson became a lawyer and defended those who could not defend themselves.” There is no reference to the fact that Mandela joined a movement. As Mandela himself noted, “No single person can liberate a country. You can only liberate a country if you act as a collective.” And Mandela could not have launched the African National Congress (ANC) since that was founded in 1912, six years before he was born. There is also little indication that the resistance to European colonization and white supremacy has a long history, dating back as far as the early 1500s when African cattlekeepers defeated Portuguese invaders.

The one example provided of a pre-apartheid struggle paints the Africans as the aggressors: “The people …. made war on the Europeans who came in search of land and treasure.” Actually, the Europeans weren’t just searching for land—they were taking it. And the Africans did not make war, they defended their land. This is much like the descriptions of colonial U.S. history when settlers were “attacked by unfriendly Indians.” The book goes on to say: “The settlers’ weapons were stronger and breathed fire.” This makes the Africans sound naive and so primitive that they attributed fire breathing capabilities to the European guns. Stereotypes about Africans are the norm in children’s literature and films as Africa Access director Brenda Randolph explains in I Didn’t Know There Were Cities in Africa.

So how is apartheid explained in Mandela? With a painting of a beach and this text: “The people were set apart. ‘European only’ beaches. ‘European only’ parks. ‘European only’ theaters.” As John Meltzer notes in Africa Access Review, “In his presentation of Apartheid policies and practices, [Kadir Nelson] privileges social segregation, what has been termed petite Apartheid. . .it is incredible that the author does not mention the core of grand Apartheid political exclusion, severe economic exploitation, and egregious social discrimination in areas of education, healthcare and housing that were at the center of the ANC’s and Mandela’s opposition to Apartheid.” The brutality of the apartheid regime does not need to be depicted in a book for young children, but it would be age appropriate to explain that blacks in South Africa did not have equal access to education, jobs, land, and physical safety. These are all institutions that are familiar to children and the concept of fairness is also understood at a young age. It would make a lot more sense to children that Mandela and others went to jail for decades to address core life needs rather than simply for the privilege of sunbathing with whites.

Likewise, the anti-apartheid movement is presented as solely focused on racial harmony. For example, the book notes that Mandela traveled to “free nations where black Liberians, Ethiopians, and Moroccans freely conversed with white Europeans and brown Egyptians. They shook hands—a glimpse of freedom for life at home. Nelson returned to South Africa to cleanse his homeland of hate and discrimination.” Actually, Mandela travelled to other countries to build support for the resistance movement. Asking others for help and solidarity are concepts young children can understand.

The few references to solidarity are posited as coming from the “ancestors.” While possibly in an effort to be culturally relevant, the use of “ancestors” in the absence of naming activists (other than Winnie Mandela) is misleading. For example: “Speaking out was against the law and Nelson was arrested and jailed for a fortnight with a hundred men. They danced and sang, calling on the ancestors to join the fight for freedom.” As Meltzer notes, “While it is technically correct that many of the songs that were used in the liberation struggle had roots in traditional songs [about] ancestors, the author’s statement leaves the impression that the primary purpose of these songs was to intercede with the ancestors, ignoring the central role of music in strengthening commitment to the struggle for freedom and justice while attracting wider participation in the movement.” This is particularly troublesome in a book that does not describe the work of other South African freedom fighters. Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, Lilian Ngoyi, Ruth First, Joe Slovo, the thousands of children who fought for liberation, and many more are replaced by unspecific “ancestors,” contributing to the otherworldly depiction of Mandela.

Of course, a Disney-like story needs a happily-ever-after ending, so here it is: “As years passed, the world pressed South Africa to change. The new president agreed, and ‘European Only’ signs came down. Beaches, parks, and theaters opened. Apartheid was no more.” The book ends with a painting of Mandela with his fist in the air, rising above a crowd of people whose faces barely make it on to the page. The text says, “South Africa was free at last.”

The movement for liberation was widespread, including people and initiatives such as (from top left) Ruth First, Joe Slovo, the Freedom Charter, thousands of children like themselves, Lillian Ngoyi, and Miriam Makeba.

Not only will this leave children confused about the current struggles in South Africa, it also misleads them about any social movement. There are milestones and victories, but the struggle to make the world a better place is ongoing. This is especially true in South Africa where the end of apartheid was by no means the end of economic exploitation and inequality. The happy ending mirrors the dominant narrative about the Civil Rights Movement in the United States: When legal segregation ended, victory was achieved. Students do not learn about the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights Movement activists’ stands against the war and for economic justice, nor are children informed that the anti-apartheid struggle was for economic justice and a vision of a new society as outlined in the Freedom Charter.

In summary, the book diminishes:

(1) the decades long freedom struggle in South Africa,

(2) Mandela’s role in a collective struggle,

(3) the struggle for economic justice, and

(4) the intellectual capacity of young readers to understand injustice and to appreciate the value of people working together for change.

What do children learn from reading Mandela? That black Africans suffered for centuries because they could not go to white beaches and that they were hopeless until Mandela came along. Mandela was all powerful and (reinforcing an all too familiar stereotype) Africans are poor and need to be rescued.

Mandela will fit neatly on the shelf with children’s books about Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Cesar Chavez. The formula for these biographies is to present the heroic individuals in isolation, not as part of social movements. So when it comes time to face injustice today, children learn to look for the next savior to come to the rescue. (Nikki Giovanni’s Rosa breaks this mold, demonstrating that it is possible in a reader friendly book for young children to tell the story of a hero in the context of a movement.)

Some will say, “But this is a book for young children. They’ll learn the true story later.” Here’s the problem. Ask any adult to name activists in the Civil Rights Movement or Farmworkers Movement. Most likely they’ll tell you the same few names they learned from picture books in Kindergarten and have learned every year since. Not only have they learned to recite the names of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and Cesar Chavez—they have learned that those people were omni-powerful and that no one else mattered. The same will be true with Mandela. If we don’t address the myth-making in children’s books, his image will be used to avoid the many lessons that can be learned from Nelson Mandela’s life, intellect, commitment, bravery, and humanity as part of a collective struggle.

I hope that future editions of this book and new books about Mandela draw on the rich stories in his life to inspire and inform young readers. This would be a real tribute to Mandela’s legacy.

By Deborah Menkart, executive director, Teaching for Change.

Related Resources

|

Africa Access Review was founded in 1989 to help schools, public libraries, and parents improve the quality of their children’s collection on Africa. Africa Access offers an online database with reviews of children’s books on Africa and hosts the annual Children’s Africana Book Awards. |

|

Books and films for teaching about South Africa, listed on the Zinn Education Project website, including Nelson Mandela: The Authorized Comic Book, Strangers in Their Own Country: A Curriculum Guide On South Africa, the film Have You Heard From Johannesburg, and more. |

|

The Politics of Children’s Literature: What’s Wrong with the Rosa Parks Myth offers a critical analysis that challenges the myths in children’s books about Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. This article from Rethinking Schools by Herbert Kohl surfaces issues that are similar to the concerns about the mainstream press and children’s book representation of Nelson Mandela. |