By Carl L. Hart

Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton all acknowledge illicit marijuana use in their younger years. Of the three, who do you suppose was most at risk for arrest and all of the associated negative consequences, including truncating his political aspirations?

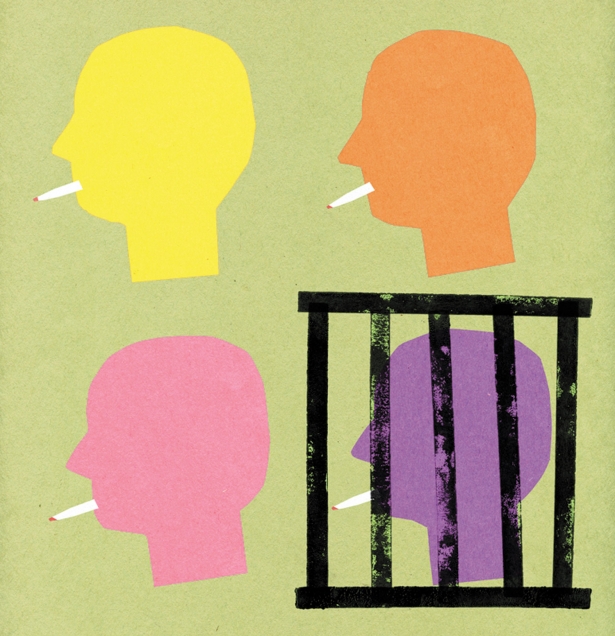

To most Americans, the answer is clear: the black guy, of course. For those for whom the answer is less obvious, consider a recent report by the American Civil Liberties Union showing that black people are two to over seven times more likely to be arrested for pot possession than their white counterparts, despite the fact that both groups use marijuana at similar rates. These disparities held up even when researchers controlled for household income. It’s about race, not class.

As a neuropsychopharmacologist who has spent the past fifteen years studying the neurophysiological, psychological and behavioral effects of marijuana, I find this particular effect of pot prohibition most disturbing. Each year, there are more than 700,000 marijuana arrests, which account for more than half of all drug arrests. And now, largely because of the selective targeting of African-American males, one in three black boys born today will spend time in prison if we don’t take action to end this type of discrimination. The gravity of this situation contributed to Attorney General Eric Holder’s remarks about mass incarceration, which he described as “a kind of decimation of certain communities, in particular communities of color.”

Throughout its study of marijuana, the scientific community has ignored this shameful marijuana-related effect. There are virtually no articles in the scientific literature addressing it. One possible reason is that the National Institutes of Health has not made it a priority to understand or prevent racial discrimination, even though the devastating impact of racism on health is well documented. The NIH, specifically the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), funds no less than 90 percent of the world’s research on marijuana. If that doesn’t include studies on race, then the research is not likely to be done.

Another reason for this blind spot is that the researchers themselves are overwhelmingly non-black and thus shielded from this kind of segregation. The luxury afforded to scientists as a result of working in a racially homogeneous field is apathy and willful ignorance, while the price paid by black people is high rates of arrest and incarceration.

The NIDA could help remedy this situation by requesting research applications that focus explicitly on race—for example, trying to understand the long-term consequences of marijuana arrests on black people, especially as they relate to disrupting one’s life trajectory.

Apathy about pot arrest racism is not unique to scientists. The major marijuana-law reform organizations, such as the Marijuana Policy Project and NORML, have also largely ignored this obvious injustice. About a month ago, I appeared on a Pacifica radio station in Washington, DC, with a director from one such group, who said: “We know there [are] stop-and-frisk policies and so forth that are terribly racially discriminatory, but we’re looking at the big picture of public health.” In his view, the racist enforcement of marijuana laws was not a “big picture” item. The more pressing issue, he explained, is correcting the erroneous belief that marijuana is a “gateway drug” to “harder” substances. I had to exercise a great deal of restraint as I listened incredulously to this person dismiss the grave injustice being perpetrated against black people.

But then I considered the racial composition of his and similar organizations. From their rank and file to their advisory boards, the membership consists almost exclusively of white, privileged and devoted marijuana smokers. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, per se, but it helped me understand why racial equality is not a central priority for them. Most of these individuals would like to light up without fear of personal legal consequences—a self-interested goal that could make it difficult to empathize with those who are actually vulnerable to racially motivated marijuana law enforcement.

Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. came to a similar conclusion in a Birmingham jail as he struggled to understand the apathy of his white fellow clergymen to the plight of their black brothers and sisters. “I guess I should have realized,” he wrote, “that few members of a race that has oppressed another race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of those who have been oppressed, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action.”

There are exceptions, however. The Drug Policy Alliance (DPA), a relatively more racially diverse organization, has committed itself not only to reforming marijuana laws, but also to opposing all drug laws that selectively target people of color. Based in New York City, it played a vital role in dismantling the infamous Rockefeller drug laws and in bringing attention to the New York Police Department’s racist stop-and-frisk policy.

I should note that I am a current DPA board member. This is less an acknowledgment of conflict or bias than it is evidence to support my point. In 2007, the DPA had two black board members—at least twice as many as other similar organizations. Concerned that this number was still too low, the leadership asked me to join the board. I accepted because the DPA understands that having a token black board member as window dressing is insufficient to effect the type of necessary change I have laid out here.

Combating racially discriminatory marijuana arrest practices will require a team effort across a variety of communities—scientific, advocacy and so on—and it is in this spirit of a shared purpose that I write. But perhaps I can be forgiven for my impatience with organizations that claim to be allies in this fight while also displaying blatant apathy concerning this issue. You see, I am the father of three black sons. I recognize that there is a high probability that they, like their white counterparts, may one day experiment with marijuana. Knowing the potential consequences if they are arrested, I cannot afford to remain silent.

I call on our allies to break their silence on this issue and make racial justice a central part of the fight against pot prohibition. The next generation is counting on you.