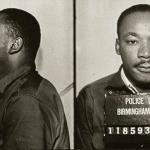

The iconic Martin Luther King Jr. whom we are encouraged to celebrate – who single-handedly ended Jim Crow with one epic, color-blind speech – bears little resemblance to the radical, imperfect man who was jailed dozens of time for his organizing within the Black freedom movement. His legacy has largely been isolated, sanitized, repackaged and labeled divine: a convenient status that encourages passive messiah worshipping over grassroots community organizing. This is no accident.

Increasingly, there are calls to “Reclaim King” as a radical [1]. It is true that his assertion of Black peoples’ right to life, dignity and reparations [2] was revolutionary. He recognized the connections between racism, war and poverty, demanding an end to the Vietnam War [3] on both moral and economic grounds (he highlighted the mass expense of war at a time of state disinvestment from Black communities). His encouragement for a “fear and distrust of the white man’s justice” challenged a central pillar of US democracy. He visited the anti-colonial struggles [4] taking place in the global South. And at the end of his life, he called for a redistribution of wealth and restructuring of our political economy through his Poor People’s Campaign [5], saying “an edifice that produces beggars needs restructuring.”

He was not mainstream: He had a 23 percent approval rating [6] among white Americans and a 45 percent rating among Black Americans. He offered a new dream, rejecting the status quo as natural, normal or inevitable and exposing the nightmarish violence and terror behind the “American Dream.” This vision shook society. And out of its trembling arms poured bombs, bullets and police dogs.

Not until he was safely buried underground was a new, less threatening King birthed and branded. This state-sanctioned, sanitized version of King has since been manipulated to discredit, delegitimize and disinform subsequent organizers who wish to continue his legacy in the current work for Black liberation.

However, the insistence that “he was a radical too” can quickly lead to a new kind of tokenization that flattens our perceptions: Ignoring or downplaying his sexism [7],adultism [8] and problematic respectability politics [9] inhibits our ability to learn from King. An honest critique of his praxis reveals the importance of centering those most at the margins – those who experience multiple forms of structural, compounding oppression (e.g., Black LGBTQ women [10]) – in order to understand the extent of Black oppression and the horizons of Black liberation.

History is a weapon and thus can be used against you. The conflation of the civil rights movement with King and the restriction of his legacy to memorialized speeches grossly misrepresent the movement he was a part of. If we want to truly honor his legacy, we have to then honor the communities, and particularly the Black women, who laid the foundation and were the backbone, heart and soul of the movement.We find the roots of the civil rights movement in the women-led campaigns protesting sexual violence [11]. Boycotts were started by communities outraged when the rapists of Black women were not held accountable by the white man’s law (e.g.,Recy Taylor [12]). And out of that – that organization and those social networks – a larger movement grew. What King did was tap into that organization. He didn’t create it and he didn’t control it. And we do him and the movement harm when we erase, minimize or silence the contributions of these Black women and their larger community.

Ella Baker [13], Fannie Lou Hamer, Pauli Murray, Jo Ann Robinson and Coretta Scott King have as much to teach and inspire in us. And their erasure from history books should be interpreted as a warning: How we tell the story of the past is more than about who gets credit for being the hero but about a battleground of interpretations of agency and the assignment of meaning. If movement memories describe social change occurring through charismatic Black male orators, we disempower ourselves by missing the ocean of resistance for the shore of what has been deemed legitimate.

King was a part of a larger movement that turned the terror of Jim Crow on itself through mass civil disobedience [14]. This movement had a wide base, numerous organizations and manifold demands. It rejected the status quo as being acceptable or fixed. It challenged and redistributed power through sit-ins, marches, boycotts and a myriad of confrontational tactics. King himself was arrested 30 times for his role in demonstrations. The movement was grounded in the defense of Black women’s dignity and freedom from rape as well as demands to end segregation and disenfranchisement.

Within this, King was one of many skillful leaders, clever tacticians and brilliant strategists. He understood that change would not come unless demanded through acts of civil disobedience, saying, “I see no alternative to direct action and creative nonviolence to raise the conscience of the nation.” Focusing too much on proving his radical politics displaces our attention on his analysis and away from his movement strategies [15]. This is not to say his understanding of the problem was or is not important, but what might we additionally learn if we refocus away from his political and economic demands on to his theories of change?

How might that instruct us to coordinate our campaigns against police violence, for example?Our ongoing debates over who King was and his role in the Black freedom struggle are of great consequence: You see, the past is never really past. Sure, things happen and time moves on. But the meaning and impact of those events remain open to those living in the present. As Angela Davis has argued [16], we must “inhabit our histories.” The sense of closure we assign to the past bars us from the knowledge and momentum of accumulated struggle. How we understand, interpret and grow King’s work today directly impacts the depth of his legacy.

We must do more than narrate the day-to-day of his life. We must open ourselves and our present up to his influence. This means going beyond our insistence that he was radical (and thus relevant to the Black Lives Matter movement [17]). In fact, inhabiting our histories requires us to realize that we have inherited an unfinished struggle, a beautiful struggle of ordinary Black people – including women, people with disabilities and people who are poor, queer, trans and young – committed to the extraordinary project of liberation from anti-Black domination. It instructs us to leverage our power through means that are disruptive, unpopular and criminalized. We must be intersectional, strategic, studious [18] and creative. We will be met with increasing violence. Our righteous rage will always be deemed irrational and dangerous. And no messiahs or superheroes will come to save us.

It is up to us, but we are not without: We have our ancestors to mentor us. We have each other to protect us. And we have our dreams to guide us. And that is plenty.

If we recognize all who are here, trying to get free, we will see that we are enough. That our lives matter. That our resistance matters. As King reminds us:

We are now faced with the fact, my friends, that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history, there is such a thing as being too late…. We must move past indecision to action…. Now let us begin. Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter, but beautiful struggle for a new world.

Free us all.